- Haworthia Update Vol. 5 – Table of Contents

- Volume 5, Chapter 1:- Winding down on Haworthia

- Volume 5, Chapter 2:- Haworthia Reality Check

- Volume 5, Chapter 3:- Haworthia Deglamorized a Recapitulation

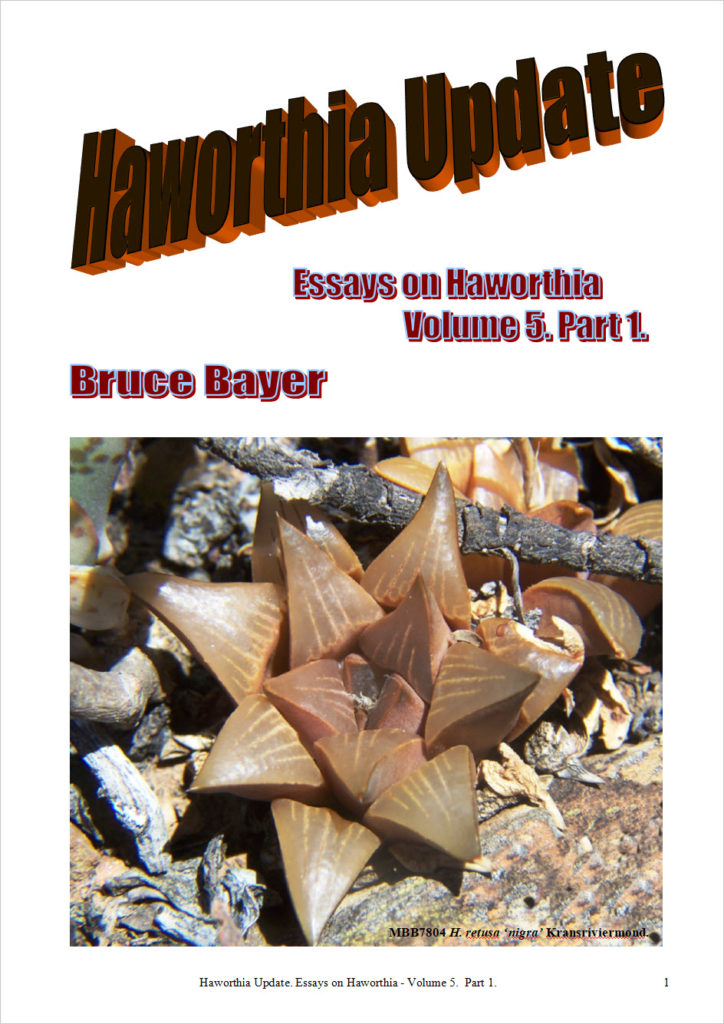

- Volume 5, Chapter 4:- Haworthia retusa – part 1

- Volume 5, Chapter 4:- Haworthia retusa – part 2

- Volume 5, Chapter 5:- Haworthia mirabilis

- Volume 5, Chapter 6:- Haworthia floribunda

- Volume 5, Chapter 7:- Haworthia minima

- Volume 5, Chapter 8:- An extension of H. rossouwii

- Volume 5, Chapter 9:- More on H. floribunda and H. mirabilis

- Volume 5, Chapter 10:- Haworthia ‘enigma’ and H. mutica var nigra

- Volume 5, Chapter 11:- What is Haworthia schoemanii?

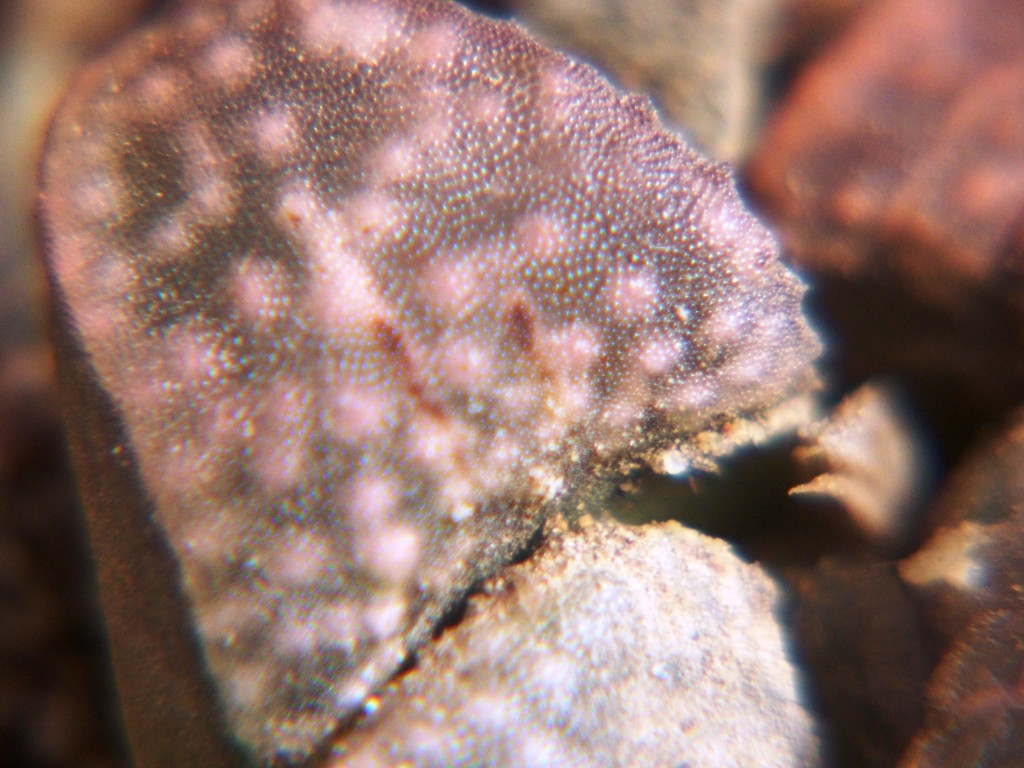

- Volume 5, Chapter 12:- More on Haworthia venosa ‘granulata’

- Volume 5, Chapter 13:- A February 2009 Miscellany

- Volume 5, Chapter 14:- Haworthia jakubii – another new species?

- Volume 5, Chapter 15:- A view of Haworthia marumiana ‘dimorpha’

- Volume 5, Chapter 16:- Can Haworthia teach us anything?

- Volume 5, Chapter 17:- New populations of Haworthia chloracantha, Haworthia parksiana and Haworthia kingiana

- Volume 5, Acknowledgements

Category Archives: Update 5

Volume 5, Chapter 1:- Winding down on Haworthia

During the last half of 2008 I decided that I would make a last concerted effort to try and further clarify the uncertainty of classification of these plants. This involves the usual introspection, retrospection and reflection. Where are we now and what do we understand? I have had considerable correspondence and interchange of ideas with many enthusiasts. There is a huge disparity between what I write and what other authors do and there are definitely massive misunderstandings. The one reason is the obvious one that we each create our own realities and can only interpret the world around us in terms of our own experience and individual capacities. The second reason is that there are flaws in the entire information system in which we operate.

Much of my correspondence has involved trying to bring someone through the very simple barrier of what a species is and what a Latin binomial is supposed to convey. Several correspondents have remarked that they follow my revision Haworthia Revisited and cannot reconcile themselves with what I have subsequently written. Particularly revealing is the reaction to a very brief item I wrote entitled “A reality check” (reprinted in this publication). In that piece I submitted six pictures of very different plants and stated that they were all the same one species. Respondents expressed surprise that I could say that these were the same (thing), basing their opinions only on the fact that the plants looked so different. They lose sight of the fact that this is the reality of “species”. The members of a species are not all the same and especially not outwardly; and to confuse the sameness of members of a genetic system with the sameness of superficial resemblance, lies at the heart of classification and identification problems.

Gordon Rowley kindly sent me a copy of an article by Sandra Knapp FLS entitled … ”Naming Nature: The future of the Linnaean System”. Erudite and academic as the article is, it exposes the fact that there is a problem inherent in the system without actually defining what the problem is. It seems to me that the alarm bells of a sinking ship are being taken for sounds inherent to the structure and performance of the ship.The problem is that here is not the universal definition of what a species is and Knapp informs us that attempting to arrive at one is ”ultimately not practical in the short or long term”. My opinion is that a statement like this simply adds fuel to the fire. We have to define the word species and in doing do recognize that in their very nature species are not equivalent.

It is botanists themselves who have led us into this morass of names where the whole process of classification and nomenclature is an intellectual and juristic minefield. As collectors, growers and enthusiasts we have come to believe that a Latin name pins a plant into place simply by virtue of superficial resemblance. This is where we fail. Knapp cites Darwin as being unconcerned that the exact definition of a species was difficult to pin down. My opinion is that this statement is at the core of the matter. It is not the definition that is difficult to pin down. What is difficult to pin down is where any plant (organism) fits in any of the boxes we want to fabricate. There is absolutely no need to vacillate about a species definition because we do not know enough about the things we want to organize accordingly.

My plea to Haworthiophiles is now to try and think clearly and recognize that the formal system of latin binomials is primarily the domain of scientists. They have not set us a very good example and we need to adapt our outlook and the way in which we approach the use of Latin names.

In these now twilight notes of mine I will use an informal system of naming and describe some really interesting experiences and finds that follow the very path that Knapp suggests will lead us forward. Gordon Rowley wryly observed that “Bayer changes his mind”. This is because I have been getting on with the job and using names, just as Knapp proposes; as hypotheses, subject to continual testing and change as I gain better insights into processes and pattern in the field where the plants are. There is a misplaced confidence in technology and laboratory based methods that simply are no substitute for the information that is needed from direct field observation and experience.

There is one very disturbing aspect. This is that there are commercial and egocentric interests in opposition to mine that may be using my information for their own interests and to the detriment of sensitive habitats and populations. It is thus very distressing to know that the joy and delight these plants have given me on so many occasions is threatened or marred by the need I have felt to write about them. I have been taken to task for revealing localities. The thing is that there can be no understanding of these plants unless the spatial and distributional aspects are known and understood. There is no way in which my writing can stand as a valid hypothesis that can be tested and refined without this critical element in the constitution of a sensible view of what species are. I firmly believe that there is no merit in secrecy. It is not my role to play policeman and neither do I think that strict conservation laws and implementation have any merit where they deny the expression of natural curiosity and wonder about this incredible creation around us. What is important is for us as individuals to realize that we live in an extraordinary creation that is a conscious one and that we are individually tied to it and responsive to it. We are responsible for it and to it: we need to get back to caring for it rather than scraping what we can out of it.

I have also not written all this because of what someone really unkindly suggested was my need to write. I am writing now because I feel an obligation to do so, having started in an era where the available classification was simply woeful and ending in a situation that is a history repeating itself. It is not about Haworthia, it is about what is true and what is meaningful. It is about how we understand nature and about what nature should mean to us. We have an incredible creation and it is time we woke up to the reality of its beauty and its purpose. God did not write a single book that so many different elements of our society claim as one that only they possess and understand. If there is any book it is everywhere around us as our birthright. ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 2:- Haworthia Reality Check

Clichés may often fall into the category of often repeated untruths that come to be believed. One I have used too often is … ”The problem is …”, without ever seemingly being to explain what it actually was. I studied Oxalis and it seemed that where there was an awful amount of detail to explain difference, all this detail simply obscured the fact of similarity. So what I did is “reverse engineer” the process and apply the principle to Haworthia where I have for so long tried fruitlessly to explain that we were all explaining and accepting that there was difference based on detail.

I made some progress in finding facts to support this contention in the approximate 40 populations of Haworthia in the Zuurberg that seem to suggest that plants looking as different as H. cooperi and H. cymbiformis may be the same species. However, this was not very convincing.

Recently I had reason to explore more populations in the arena of a larger problem in H. mirabilis where I may be considering as many as 400 populations or many more. Illustrated by the following sample pictures: … It is now my contention that different as all these single plants appear to be, they are in fact members of one species. The inference is drawn from observations of approximately 150 populations occurring in a geographically coherent pattern in the restricted area between Worcester and Riversdale and southward to the coast. The inference is strengthened by the observations of similar continual intergradation of variation in similar sets of populations throughout the distribution range of the genus.

I do think that this is evidence to put to rest the disputes about the classification of this group of plants. But I do think that there are implications for plant taxonomy in general perhaps starting simply in the Alooideae where there is such confoundment in the understanding of simply the genera. ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 3:- Haworthia Deglamorized a Recapitulation

Steven Hammer, in his inimitable style, put a very fresh face on Haworthia in Cact. Succ. J. (Los Angeles) 80:140 (2008). He drew attention to the wonder of the plants in cultivation for the collector, contrasted to a reality of unglamorous scruffiness in the field as per the lens and pen of Bayer. It has fallen to my lot as a very unwilling taxonomist to reduce the fascination these plants have for me, and for so many others, to the mundane vortex of labels, their proliferation and continual amendment. The fact is whether on a label or on the tongue, a name is a part of any language we use to talk to each other; but we are not learning anything from a well-documented history and in Haworthia seem to remain lost in a maze.

The unhappy truth for Haworthia is that by the time von Poellnitz in Germany, G.G. Smith in South Africa, F. Resende in Portugal, A.J.A. Uitewaal in Holland, W. Triebner in Namibia, J.W. Dodson and J.R. Brown in USA had either left or abandoned the scene, there were any number of names that meant very little more than the Latin they were written in. J.R. Brown presented a talk, A brief review of the Genus Haworthia, to the Los Angeles Cactus and Succulent Society that was published in the Cactus and Succulent Journal of America 29:125-135 (1957). He noted the number of species and varietal names at 160 and 370 (!) respectively, arranged in 20 sections.

While J.R. Brown was winding down (his last note on Haworthia was published in 1970), I was busy trying to make sense of a two large files that seemed to form the body of a manuscript by G.G. Smith for which Mrs. M. Courtenay-Latimer had drafted a title… “A monograph of the genus Haworthia.” This manuscript comprised a collection of all current species descriptions arranged in the purported twenty sections of Berger and accompanied by many illustrations from the original publications, as well as by many of Smith’s own photographs and those of H.G. Fourcade. We know that Smith retired in a huff, but was there really good reason for his exit?

It is quite evident from the legacy of notes that the manuscript could not have been anywhere near complete. I drew attention to this in an article…”Reflections on G.G. Smith’s Haworthia collection” that was published in Excelsa 8:46-52 (1978). While stuck in the paradigm of 20 sections, he envisaged many more species and varieties and I cannot imagine how he could ever have reconciled this with the evidence of his compiled manuscript. I suspect he realized this too, hence the (self-directed?) huff.

It took me several years to absorb the specimens in the Compton Herbarium while at the same time taking Smith’s meticulous (in the sense of the literature from which it was extracted) collation of material to pieces. Putting it all back together as best I could, I eventually produced Haworthia Handbook (1976) published by National Botanic Gardens of South Africa. It was not a great work and neither was it very well-received at the time (though it has had a curiously perky afterlife once it went out of print). Charles Glass wrote to me that he was a bit disappointed (by its elliptic compressions?). Gordon Rowley was kind enough to point out many nomenclatural errors and a page of errata had to be inserted.

However, I was actually committed to helping Col. Scott write a formal revision as I had no aspirations to do so myself. He had been refused access to Smith’s collection, as the Curator of the Compton Herbarium had concurred with Mrs. Courtenay-Latimer (and perhaps Smith himself) that Col Scott would not do credit to a formal revision. It became quite problematic for me when I realized that this estimate of Scott’s botanical capability was uncomfortably close to true. This led me to re-write my handbook as The New Haworthia Handbook (1981), also published by National Botanic Gardens, hoping that Col. Scott would follow the ideas expressed in my optimistic foreword.

This did not happen and Scott’s…The Genus Haworthia – A Taxonomic Revision, appeared in 1983 published by Aloe Books, Johannesburg, as a closely and clumsily kept secret from me.

My honest opinion is that this book was a total disaster, taxonomically though not photographically, and it was most disheartening and confounding to consider that the flattering introduction was by Dr. L. E. Codd, then head of the national Division of Botany and of the Pretoria Herbarium. Not only that, Dr. Beth Gibbs Russell later telephoned me to ask whose version of Haworthia the herbarium and the institute should follow! I do not know what my response was other than thinking how unfair it was to place the onus on me to judge. Whatever I might have said, that did not stop the institute from publishing an extraordinary mish-mash of names for Haworthia in a national species list taken from Scott, myself and other sources. It was simultaneously no comfort to welcome the grand old man of Haworthia, J.W. Dodson, to the Karoo Garden. Bewildered by what he saw in the collection there, he could do no more than express his conviction that Col. Scott had produced a very workable revision!

As far as I was concerned, Haworthia was all emptied back into Smith’s “monograph,” and readers may imagine why I found this so disturbing. Around 1993-4 news of a new succulent lexicon to be compiled by Urs Eggli to replace the famous Jacobsen set was circulated. At the same time, by virtue of my contact with the Compton Herbarium, I was asked to write a synopsis of Haworthia for a list of plant species for the Cape Flora. These were the defining factors that led me to writing a formal revision. I cannot bring myself to detail the communications with other aspirants to taxonomic fame then and since, as these border on the bizarre and do nothing more than add to the disrepute of taxonomy in the minds of plant collectors who care about and are compelled to use Latin names.

When I eventually wrote my revision I had no illusion that it would be the last word on the subject. Indeed it seems in retrospect that it may well have been but the first! Not only has there been an explosion of new names and opinions, I have also been driven to examine and re-examine those areas of my understanding built not only on available field knowledge and exploration, but also on Smith’s vast legacy. It is necessary to note that the contributions of people like Jay Dodson and J.R. Brown played no small part either. The little book written by Brown, viz., Succulents for the Amateur, played such a significant part in cultivating my interest in plants that I have been very sensitive to the resonance of the devotion and interest Brown showed for Haworthia. This respect for others like F.R. Long and H.G. Fourcade, whom I never met, extended to people like Frank Stayner, G.J. Payne, Gordon King and so many others I met solely as a consequence of these plants. That the human relations aspect of their classification and identification took such a downturn in the wake of Smith’s criticism of, primarily, Resende in 1947 is a sad record in history. Relations never recovered and my involvement in and distress at the later half-repetitions of history is at the heart of this article.

Since 1995 my accession records have climbed from 6400 to 7700 and these numbers represent almost entirely new population records for Haworthia and I trust that I have not used my own numbers where a very few contributing collectors have helped me. I have written innumerable articles for Haworthia journals while Umdaus published Haworthia Update Vol 1 in 2002. This seems to have been a commercial failure but my belief is that editors and publishers have never understood the issues. I could not help because despite my excessive attempts to explain the problems causing strife and confusion in the literature, I really never exposed the heart of the matter. Fortunately for me Harry Mays of Alsterworthia kindly published Haworthia Updates Vols 2, 3 and 4 between 2003 and 2007.

In these volumes I tried to address the realities of variation and the confoundment that exists in my own and the communal mind, about what species are or might be as related to a perceived botanical and scientific process for naming plants. But if 40 delegates could be brought together as happened recently in an effort to create a united front just for the single genus Aloe, it does seem fairly senseless to be functioning so alone in Haworthia where a greater need exists. In my “unsparing” view of things I find it extraordinary that the symposium did not seem to address the wider problem of genera in the Alooideae. I am quite sure that if this were done first, it would facilitate the common understanding of lower ranks. In Haworthia there has been absolutely no common will to reach any kind of consensus and no reason has been found for that. My conviction has grown that Latin names, and the way the nomenclatural system is used, do nothing more than strain good will in that they implies a reality in a staged relationships of plants that is simply not true. If I were a more dedicated taxonomist I would have simply worked towards a functional generic arrangement: Haworthia for the glamour queens, Jayarbia (honoring J.R. Brown) for the Hexangulares, and Catevala for the Robustipedunculares.

I recently submitted a short list of names that I think should serve Haworthia to the Haworthia Society in England. As Gordon Rowley pointed out in a letter to me… “The problem is that Bruce Bayer changes his mind.” Well, I do want to change my mind about that list again. I would advise incorporating H. heidelbergensis, H. magnifica and H. maraisii and their variants all under H. mirabilis. Furthermore I would suggest abandoning the formal lower ranks of subspecies, variety or forma for appended third epithets in inverted commas. The list of species is thus reduced to a realistic 54.

But there is still a wealth of undiscovered things out there and the many existing names mean very little to me in understanding what I have seen and continue to find. So I give a brief overview of the product of very recent fieldwork where in less than 10 days my wife and I found 24 previously unrecorded Haworthia populations. These included two populations of H. floribunda, one of H. retusa ‘nigra’ (implementing a name change and a new way of expressing difference), five of H. rossouwii, one of H. minima, one of H. marginata, two of H. mirabilis ‘paradoxa’ and 12 of H. mirabilis. While each of these has a story attached, I am only going to touch on the latter.

I have written in detail about H. mirabilis in Haworthia Update 3:87 in a chapter that deals primarily with the populations in the western area of the distribution. I also wrote in detail of associated plants in Update Vol. 2:51-79 dealing with populations east of Heidelberg in the eastern area. So these new populations are relevant to the central zone and I will add several others that were found earlier but subsequent to the Update 3 publication, plus another by Marc Mougin (brought to my attention by Diederik Van den Abbeele). They all deal with an area extending eastwards from Stormsvlei and the Bromberg Mountain to the Karringmelks River southwest of Heidelberg and southwards to Koppies and Stuurmanskraal, where there are populations already covered in Updates.

Five of the populations can be unequivocally assigned to H. mirabilis ‘atrofusca’ and yet with a fair degree of variation. These are all just west of Heidelberg. The other seven that do nothing more than confound understanding of anything that can be construed as H. maraisii, H. magnifica, H. heidelbergensis or H. mirabilis, occur southwest of Heidelberg and extend westward to Diamant (east of the Bromberg). The only significant thing about the two groups is that where ‘atrofusca’ is evident in the populations, H. floribunda may be in the vicinity. Where H. floribunda is not present the seedlings resemble that species as an odd indication that perpetuated juvenile characters underlie the species floribunda. The variation within the populations is quite dramatic and it is indeed difficult to verbally report and sensibly convey this to a reader. The plants vary in size, texture, markings, leaf armature, color and translucence. So I submit pictures with the manuscript and offer the following comment as best I can:-

A map is provided as Fig.1. Greater Swellendam area to show positions of Haworthia populations noted.

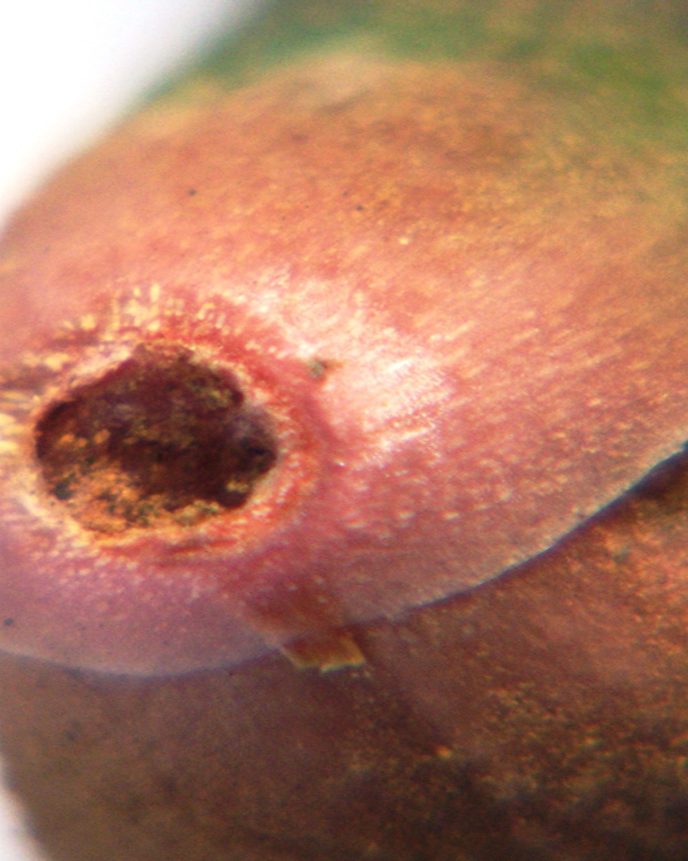

1. MBB7254 Bromberg. (Fig. 2). This really belongs with a large set of populations extending westwards and north along the Riviersonderend Mountains and into the Robertson Karoo. I start with it because it serves as a virtual ‘outgroup’ — and this is because the southern slopes of the Bromberg are different to the northern slopes. They are quartzite (silicon oxides) sandstones and the northern slopes felspathic (other silica salts). This difference in mother material manifests itself in the Haworthia populations and can be used to explain why H. maraisii v.Poelln. in the shales and siltstones at Stormsvlei are so different to H. mirabilis ‘depauperata’ VPoelln. in the quartzitic sandstones less than 1km north. The plants are relatively small and have the reddish color often associated with H. mirabilis south of the Riviersonderend Mountains.

2. MBB7612 Diamant W (Figs 3 & 4). These are very big plants up to 110mm in diameter with a similarity to ‘maraisii’ by virtue of their blackish-green color and more retused (bent back) leaves. The classic difference of ‘maraisii’ and mirabilis as being separated by translucence absent in the leaves or present, is again flouted in this population as in so many others; and similarly leaf surface texture is variable. The significant thing is that the mountain they are on is an extension of the Bromberg (Riviersonderend Mountain tail) but it is the northern slope and the sandstones are felspathic.

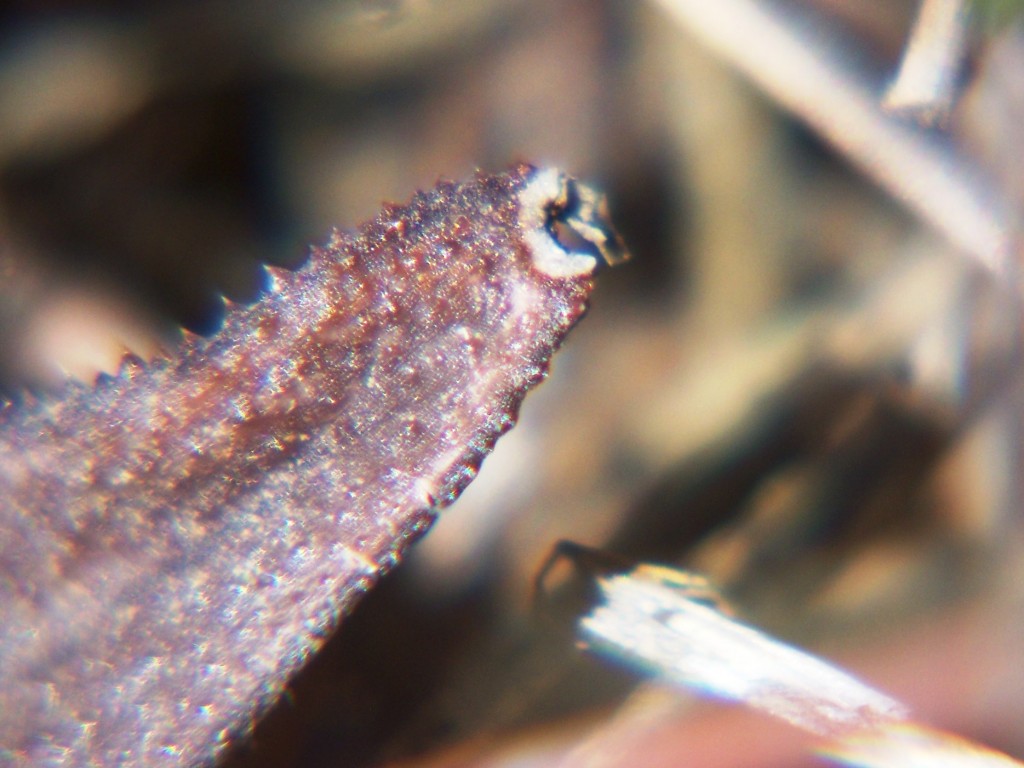

3. MBB7626 Diamant Mid (Figs 5 & 6). This population is less than a kilometer east of the receding on a more eastern and thus cooler aspect. The plants are a little smaller, the leaves generally more erect and are a little more reminiscent of mirabilis to the southwest in that spines are better developed on the margins and surfaces than in the case of classic ‘maraisii’ (I am trying to show that ultimately there is no infallible distinction).

4. MBB7718 Diamant E (Figs 7, 8, 9 & 10). This is a huge population on a lower elevation than the preceding and the skeletal habitat is significantly different. It is on the interface of the Felspathic sandstone and shales and siltstones of an older formation while a strong vein of quartzite transects it. In addition there is evidence of an eroded away, and later, ferricrete deposit. The plants are also extremely variable, reflecting the range of divergent surfaces although generally much smaller than preceding. Leaf surfaces are mostly roughish.

5. MBB7633 Luiperdsberg (Figs 11 & 12). A small population quite high up on a slope of felspathic sandstone. These are small plants and because of quite a grassy habitat the leaves are a little elongated generating the range of forms that I have generally assigned to a little understood or known range of plants and populations in H. ‘heidelbergensis’ Smith.

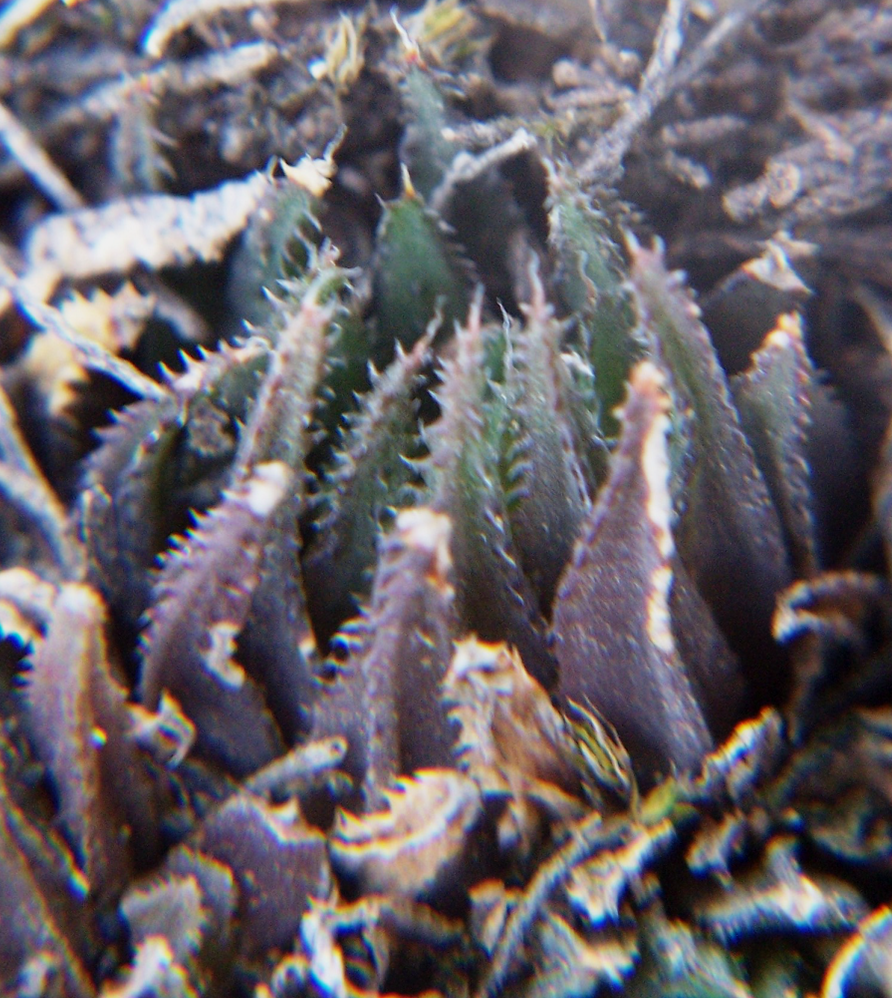

6. MBB7719 Dagbreek (Figs 13, 14, 15 & 16). An established population in felspathic sandstone but marginal to shale and siltstone. Very grassy but with occasional rocky ridges so that the plants are concealed in grass tufts or wedged in crevices. The plants are moderately sized to 60mm diameter and differ in that many have a rather smooth surface with corresponding finer and more closely spaced marginal spines. Some plants develop a shiny opacity about the leaf tips that suggest surfaces perhaps comparable with the smoothness of the H. retusa complex.

7. MBB7704 Bontebok Park (Figs.17, 18, 19, & 20). There is an earlier collection (6644) from the ferricrete/shale interface alongside the N2 highway near the northeastern corner of the park, which I considered belonged in a series of five populations that seemed to be neither H. ‘maraisii’ nor generally accepted H. mirabilis. It is on ferricretes but there is some problem how to relate this apparent river terrace gravel with the solid caps of the inselbergs to the east and west. There is nothing common in the general suite of species that could be described as Fynbos on the former and grassy Renosterveld on the latter. The plants are moderate in size; surfaces can be quite rough with a tendency to spination, and the marginal spines quite coarse. Leaves erect or spreading.

8. MBB7705, 7706, 7713, 7714, 7715 Uitvlugt (Figs 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, & 26). These are five quite independent populations on the one farm that is unusual in that it seems to be on predominantly an earlier variant of Cenozoic ferricretes. The plants are generally related to H. ‘atrofusca’ with rounded leaftips and roughish surfaces. The actual habitats are all different in respect of surface detail and associated vegetation. The plants vary in size between the different populations from small (30mm diam) to large (70mm diam). In the one site where the soil is whitish bentonite, the plants are small and also have a curious similarity of color to that of the clay and the associated plant Gibbaeum haaglenii (austricola).

9. VA-RW07-27 (Figs 27, 28, 29 & 30). This population located by M Mougin, was reported to me by D. Van den Abbeele. It is much closer to Heidelberg and obviously in a ferricrete related habitat. The plants are all very ‘atrofusca‘-like with some evidence of the pointed leaf-tips that would have been ‘magnifica’. The surfaces have the slightly riffled texture that one associates with ‘atrofusca‘ rather than the tendency to roughish surfaces or almost spinescent tubercles associated with, but not peculiar only to ‘magnifica’.

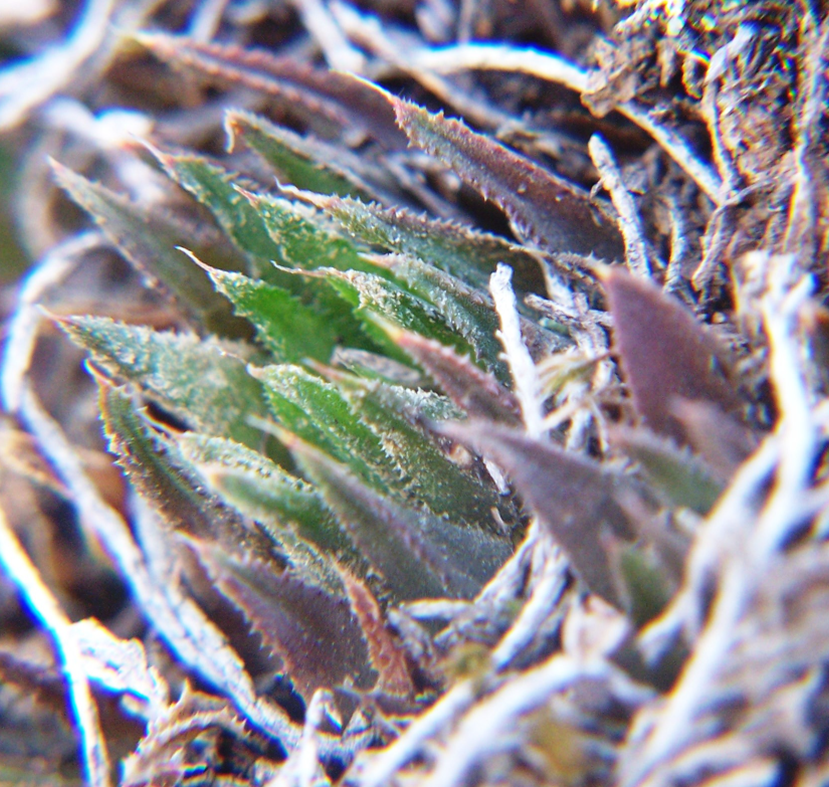

10. MBB7728, 7729 Lilliendal (Figs 31, 32, 33, 34 & 35). The significance of these two populations must be emphasized. The place is the Karringmelks River southwest of Heidelberg. This river drains into the Slangriver that flows then southwest into the Breede River. It is quite a different drainage basin to the Klip and Duiwenhoks rivers that drain the area north and west of Heidelberg and enters the sea south of Heidelberg. Matjestoon and the origin of H. ‘heidelbergensis var. toonensis’ is south of Lilliendal and on the same drainage system. The plants would at the time have made it difficult to imagine H. ‘heidelbergensis’ as a discrete system, and these plants force a direct comparison with H. ‘maraisii’, if that system could be generalized. The plants are small, dark-green, rough and with a degree of spination on the surface tubercles. Surfaces may be opaque or translucent. There is a striking resemblance of the seedlings to H. floribunda. The populations are about 1km apart. Both are on Bokkeveld but at the second population it is curious to observe that the plants are not on the ferricrete only meters away.

11. JDV87-3, MBB7165 Matjestoon(Figs 36, 37 & 38). This is one of the original populations known to G. G. Smith and it is an uncomfortable fit anywhere on account of the length and spiny-ness of the leaves. That the plants were placed in ‘heidelbergensis’ is a reflection of the doubtful and composite nature that the species gained by default. There is a semblance of similarity to H. rossouwii but what may be more notable is that at Dassieklip to the southeast there is a very aberrant population that is assigned to H. floribunda simply for want of a more likely category. I say this is notable because in my field observations of Haworthia there is a very strong and predictive geographic continuity between populations. This is evidenced in this general discussion.

12. MBB7736 Koppies (Figs 39 & 40). These are small dark-green plants with strongly deflexed leaves and a little unlike an earlier record from 2km west (MBB6879 ex E. Esterhuizen) where the plants have more pronounced surface tubercles becoming quite robust and dark in cultivation. The habitat is among white quartz occasionally associated with ferricrete.

13. MBB7723 Stuurmanskraal (Figs 41 & 42). These rank among what might be regarded as the general body of H. ‘maraisii’. Small, dark roughish plants with strong evidence of floribunda in the way the leaf-tips tend to be flat, twisted and rounded. The habitat is Bokkeveld shale.

14. MBB7734 Stuurmanskraal N (Figs 43 & 44). This is a previously known population similar in its responses to the Koppies plants (MBB6879) that become quite robust and dark in cultivation. The habitat is white bentonitic clay that develops under the ferricrete sills from decomposure of underlying shale.

15. MBB7731 Oudekraalkop (Figs 45, 46 & 47). Finding this population at all suggests that there may be many more evading the eye. The plants are small and dark and completely hidden among dense but short vegetation on a rocky scree-like area. As in other populations one is compelled to look at every plant and consider its departure from a hoped for norm for the plants there. Three illustrations hardly do justice to the variability and this true for all these populations discussed here.

Conclusions

My despair over the years that I have been involved with Haworthia, is that the classification model and nomenclatural system we use, does not seem to allow me the freedom to express what I have seen and experienced. My argument has been that we are dealing with a biological system in which things that seem different are the same; and conversely things that seem the same are different. It is not a problem to apply a formal classification system except that a ranked or tiered system suggests quantum differences too, and this is simply not true. The greater problem is that most plant enthusiasts, and those who feel strongly about classification and names, confuse the reality of the sameness that suggests ‘species’ with the sameness that plants of different species may exhibit.

It is with a source of considerable curiosity that I now take note that a taxonomist is one who classifies by appearances and a systematist one who classifies by evolutionary pathways. In truth I never considered that classification was anything but an attempt to accomplish both aims so that meaningful names could be established. The issue is clouded in complexity when it is considered that neither taxonomist nor systematist may be sure when a species is a species. Probably hence the observation that species (binomials) carry a reality they do not possess. My proposal, supported by the observations in this article, is that we adopt a far more informal and flexible approach to the use of all the names we now have at our disposal. This suggestion is also supported by an experienced taxonomist/systematist/botanist who wrote: “The informal system that I prefer allows for endless forms that are identifiable by their locality and do not clog up the literature. Essentially it is a reversion to the polynomials of the pre-Linnaean era.”

My contention is that the only rational classification of the above 20 populations is within a greatly expanded concept of H. mirabilis that includes H. maraisii, H. magnifica, and H. heidelbergensis. This corroborates the observations reported in the chapters in Haworthia Updates and specifically Chapter 6, Update 2,1:50-79 “How to understand H. mutica var. nigra”, and Chapter 1, Update 3,1:1-87 “H. mirabilis and the interface with H. maraisii”.

Acknowledgements

The population MBB7704 was shown to me by Ms. Tineke Kraaij of RSA National Parks Board. The concurring botanist is Dr John Manning, who has authored many botanical works and who is best known for his familiarity with the highly complex Cape bulb flora. Dr. Syd Rhamdani introduced me to the new direction that molecular biology is driving plant systematics. Gerhard Marx has been a great help in getting me to resign to the unrealities of popular taxonomy. Steven Hammer, considerably more successful than I have at adapting to the fact that our perceptions about many things are very different to that of others, helped me with the manuscript. Rhett Hiseman of Cape Nature, Jaap Viljoen, Henniie and Elma van Deventer of Koppies, the Odendaals of Dagbreek, Diamant and Dankbaar, Alfred and Andrea of Lilliendal, Dirk Papendorp of Uitvlugt, D. van As of Stuurmanskraal, Anna and Arno Steenkamp of Oudekraalskop (Anna’s Farm) are sincerely thanked for information and/or access to plants. ♦

References

Bayer, M.B. (2006, 2007, 2007) Haworthia Updates Vols 2, 3 & 4.

Alsterworthia International UK.

Volume 5, Chapter 4:- Haworthia retusa – part 1

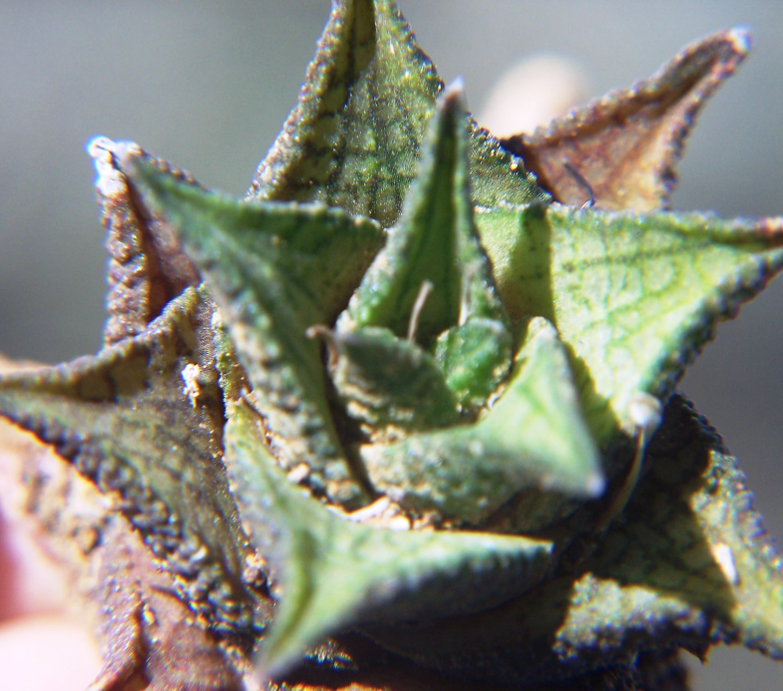

It has long been my stated contention that H. turgida is in fact a rock face ecotype as opposed to the solitary flat growing H. retusa. Thus one should expect the multiplicity of forms that are found between, and consequently superfluous to say within each, these two primary types. There are problems outside of this and I will deal with those in the Chapter Haworthia enigma. Here I am simply going to present pictures representing plants in nine populations of the species. Most of these populations are of the “typical” solitary form and they all demonstrate variation to greater to lesser degree. Perhaps some special mention should be made of the element H. mutica var. nigra. I have written at length about this and in doing so strayed widely into H. magnifica and its var. atrofusca (both falling now under H. mirabilis). This is because it is quite certain that there is an element of interaction in the field between the prime elements H. retusa and H. mirabilis that this summation is intended to expose. The first known H. mutica var nigra from Kransriviermond is possibly the product of such interaction, whereas all the subsequent collections from northwards and westwards are now perceived by me to be variants of H. retusa and H. retusa ’turgida’ (to use a more informal and flexible way of communicating).

1.MBB7776 Pienaarsrivier. This is a population just west of Kweekkraal and the agglomeration of populations that I dealt with in a series of articles covering the diffuse nature of ‘nigra’. The population was first brought to my attention by Etwin Aslander but finally shown to me by Kobus Venter. It is extraordinary that it is not better known in the literature and again a vivid demonstration of how thoroughly one has to explore to uncover the mysteries of what constitutes species. It has always been difficult to adequately illustrate plants and probably the very weak appreciation we have for variation is precisely due to the fact that often species ere even described without any accompanying illustration. If there was one it was taken to be the exact image of many such that could all go by the same one name and this a Latin binomial. This is the paradigm that needs to change.

At Pienaarsrivier, the habitat can be described as an erosion product of the ferricreteinselbergs that are so characteristic of the lower areas of the Southern Cape. However, it is an extremely complex situation as there are high and low level gravel terraces as products of direct erosion off mountain sides, river gravels as a product of countryside drainage and then the iron rich ferricretes themselves as the products of deposition along groundwater movement. Here at Pienaarsrivier there is dense Renosterbos and grass among fairly large sized stones. The plants are abundant and they flower in October. I have elsewhere shown pictures of H. retusa from both eastwards at Kweekkraal (two populations) and from Heidelberg itself (many). The Pienaarsriver plants tend to have a very purplish hue and often the leaf tips are very rounded (mutica!) ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 4:- Haworthia retusa – part 2

2. MBB7754 H. retusa ‘turgida’. Brakkekuil. What is most significant about this population is its whereabouts that highlights the overwhelming importance of distribution and geography. The drainage systems (or parts of them) of the Southern Cape drain southwards from the mountains to the sea e.g. Gouritz, Goukou, Duiwenhoks and Lower Breede. These are important especially when it comes to the habitats in the way of exposed rock and steep faces that favour plants requiring skeletal soils. Brakkekuil is on the Slang River that drains southwestwards from near Heidelberg to flow into the Breede River near Malgas. H. retusa ‘turgida’ has not been reported for this entire river system before, while it is present on the Breede River and even westwards at Bredasdorp. So the Brakkekuil population is significant and also significantly different. The plants are neither strictly solitary nor greatly clump-forming and it is not really surprising as this mirrors what happens with H. cooperi in the Eastern Cape in situations that are neither fully cliff face nor plain. The Brakkekuil plants are on the surface of a rocky shale knoll with plants enduring direct exposure to northwestern sun as well as obtaining refuge in the more vegetated and protected slightly southern aspect. It is quite difficult to make reference of individual plants to Latin names, in that variation is already ensconced in the existing system viz. ‘longibracteata’. I gladly concede that all the old names, as Rowley has suggested, can be paraded out again and made use of. In fact I have also said that this is how the contribution of Breuer and Hayashi can be fruitfully used. For my reality this population is H. retusa ‘turgida’ Slangrivier. It is quite the most variable population of the ‘turgida’ side of H. retusa that I have ever seen and there are plants that resemble the more sandstone associated variants (‘caespitosa’) at, say, Tradouw Pass as well as individuals that compare with some of the other populations I will cover from the ferricrete inselbergs. Another very significant observation is the similarity of some plants to those that can be found in H. mirabilis ‘paradoxa’ that is not very far away to the southeast at Vermaaklikheid. There is no doubt that if a full and real understanding of natural systems is to be found it will lie in the realization that even my suggestion favouring a “super species concept” may be conservative. It is actually curious how my treatment of that has been met by readers who have been kind and considerate enough to communicate with me on the issue. The ‘super species” proposal actually comes from Prof. Canio Vosa. It is and was not, any attempt to confound anyone or obfuscate the issue. Prof. Vosa is directly addressing the issue that we have a classification that is a sorry marriage of scientist and layman user groups – both ignorant of the full extent of the field situation.

3. MBB7556 H. retusa ‘longibracteata‘. Dassieklip. There are ‘turgida’ populations all along the Duiwenhoks River. Some of these could be ‘turgida’ and some could be the variant ‘longibracteata‘. These at Dassieklip are close to the latter and are reminiscent of some of the large slender leaved plants one finds close to Heidelberg itself

However, the two plants illustrated are a few hundred meters west of the river and survivors of road materials quarrying. There are many more plants along the river itself and also at Brakrivier between Dassieklip,and Vermaaklikheid. But south of Dassieklip the river drainage passes from shale to calcrete and something really interesting may occur on the interface of these two geological formations northwest of Vermaaklikheid. Curiously no H. retusa is recorded at all between Brakrivier and Stilbaai to the east and this may be due to the calcrete substrate and the absence of suitable habitat.

4. MBB7758 H. retusa ‘retusa’. Skietbaan. Riversdale. This is a very well known population and one of many in the general area extending slightly south and then west rather than east, although there is a population in the rocks of the Goukou river itself to the east. The plants are on a shale substrate and huge with again the expected variation that has been so obscured by the limited illustrative material of the historical past. The habitat is highly disturbed and it is in fact surprising that it has survived here so successfully. A road and a fence cross the site that follows the scale of the relatively confined areas the plants are usually found in. There are a heap of epithets that could be mobilized to personalize these plants and even ‘solitaria’, ‘geraldii’ and ‘fouchei’ could probably find application despite being out of true context.

5. MBB7240 H. retusa. Skeiding. This population seems to be very relictual and I did not see many plants. I include it just to indicate that these ferricrete associated forms are here and they are trespassing into the series of populations that I discussed in the ‘mutica var. nigra’ story. That I now could refer to these as H. retusa ‘nigra’ should be seen as evidence of the flexibility and pragmatism that is really required to allow acceptance of a nature that we can understand.

6. JDV93/57 H. retusa. Plattekop. There are several populations in the ferricrete inselbergs. They are inclined to shiny yellow colours and rather longer, more erect leaves than one would expect in H. retusa. In fact one can see a drift from the latter to ‘longibracteata’ in the broader context that I originally used the name to really suggest populations that were neither ‘retusa’ nor ‘turgida’. This particular habitat is unusual in that the rock is larger than usually accepted by the plants and there is quite an infusion of the white clay of decomposed shale. The plants seemingly, and consequently, take on a rather powdery and milky appearance.

7. MBB7772 H. retusa. Platkop Annex. Where Skeiding is west of Heidelberg, Plattekop and Platkop Annex are east of Riversdale. These and the next two populations form an important extension of the distribution of the species eastwards and to perhaps emphasize a distinction between H. retusa as it grows on the inselbergs as opposed to H. retusa ‘turgida’ that is riverine.

8. MBB7765a H. retusa. Plaatjieskop. These plants are very similar to the two preceding. A similar population was shown to me by Japie Dekenah at Rooikoof to the north. What is significant here is the presence of hybrids with H. floribunda (fig. 74) and that in turn by the fact that H. retusa flowers in spring and H. floribunda in summer. Such hybrids are known at Cooper siding between H. pygmaea ‘argenteomaculosa’ and H. floribunda and also at Blackdown, N. Heidelberg between H. retusa ‘turgida’ and H. floribunda. Because I consider that there is a deep-seated ‘problem’ of interaction like this between major role players, I will discuss this again elsewhere.

9. MBB7771 H. retusa. W Soetmelksrivier. There are seemingly always surprises in Africa (“always something new”) and this is one. Not only does H. retusa grow in direct association with H. mirabilis cf. ‘splendens’ but the habitat encroaches on the highly ferruginous rocks that form the hardest layer of the ferricrete inselbergs. It is really only two populations in the Kweekkkraal area where haworthias can be said to be truly in this kind of rock. ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 5:- Haworthia mirabilis

I trust that it is clear by now that I consider H. magnifica, H, maraisii, and H. heidelbergensis to be essentially the same one species and emphasize that it is really a self-evident truth that species are complex systems and not simply a randomly occurring set of similar looking things. In a recent manuscript submitted to Haworthiad, I wrote about new finds elaborating this point of view. The essence of this chapter is to discuss exploration focused on clarifying the position in the eastern area between Riversdale and the very problematic H. pygmaea “squadron” that I have also discussed at length. Prior to the trip I had an ongoing communication with Gerhard Marx and we agreed that H. ‘splendens’ was in fact better fitted in H. mirabilis, the major obstacle for me being the fact that there was no field record nearer than Riversdale itself to substantiate such a view. I do, however, want to here also record two further populations east of the Breede River and other populations of H. mirabilis west of the Breede and south of anything previously noted.

1. MBB7442 H. mirabilis. Dankbaar. This population is of small plants but they are not substantially outside of anything noted in any of four compass directions although they do have their own look about them. I found it quite odd that Cameron McMaster had sent me pictures of a population of H. mirabilis from Fonteinskloof to the southwest of Stormsvlei that reflected the same co-similarities with H. mirabilis and H. marasii that I had recorded at Rondeheuwel south of Stormsvlei. The Dankbaar plants are small versions of this and of course tie up with both older and newer (MBB7704) records for the Bontebok National Park.

2. MBB7744 H. mirabilis. Bontebok Park. Having written that, we did in fact locate still another population and of course it looked different as the area where it occurs had been recently burned and being on a northwest aspect the plants were very exposed and even more cryptic than usual.

3. MBB7749 and MBB7751 H.mirabilis. Kadies Landing.: These two populations are in my opinion tremendously significant. While H. mirabilis has been reported from this the east bank of the Breede River, it was a very small form such as I recorded for the lower west bank (Ziekenhuis, Aalwee). The plants we located are down the river from Malgas but on the east bank. They are not any smaller than the general size of H. mrabilis anywhere in the central area of the range and highly similar to the plants especially in the Bontebok park quite some distance upstream from a very winding river course. There is thus now a very substantial connection and continuity from west to east and into ‘atrofusca’ that occupies the inland upper areas from west of Heidelberg to east of Riversdale.

4.MBB7753 H. mirabilis ‘toonensis’. Brakkekuil. It is important to note how I have named this as I have no intention of going through the formalities of nomenclature to change anything. I have been terrorized to my limits by “law” and I think that ethic and common sense can now prevail. ‘Toonensis’ is only known from Matjestoon southwest of Heidelberg and upstream along the Slang River. As I explained in the chapter on H. retusa, the Slang River has its own peculiarities and besides which it is quite unexplored. So it is no surprise to find this rather smaller version of H. mirabilis in a second population, differing from the general body by more and smaller more slender leaves. Naturally there is considerable variation within the population too. The differences relate to the problem of the Dassieklip and Vermaaklikheid areas where H. retusa and H. mirabilis ‘paradoxa’ and the problem should not be deferred to me as a bad taxonomist but as the reality that there is a major geological contributor to the problem of difference viz. shale vs calcrete. It is quite obvious in the series of pictures that one can see resemblances to ‘turgida’ and ‘paradoxa’.

5. MBB7761 H. mirabilis ‘splendens’? Plattekop Farm; MBB7762 do. W Platkop; MBB7763 do. E Plattekop Farm, MBB7765 do. NNW Platkop: MBB7769 do. Toringskop; MBB7770 do. W Soetmelksrivier. I am grouping these together and using the epither ‘splendens’ in an apparently loose and provocative fashion. This is to deliberately hew away at this mental sludge that isolates the really magnificent and incredible plants from their equally interesting but less glamorous close relatives. These populations are all on ferricrete inselbergs in virtually any of the three or four main geomorphological derivatives. The official geosciences description of the Riversdale area makes specific mention of the difference between these and the Soutpan (true ‘splendens’ habitat) by saying that the latter is a pan-area and the relatively thin ferricrete layer apparently developed in a marshy area and close to the surface (opposed to the inselbergs as deeper deposits in underground water systems in sandstone?). These populations are what we predicted and they are the direct link between the most easterly known only true H. mirabilis ’magnifica’ at the Frehse Reserve just south of Riversdale. The element ‘magnifica’ is a phantasm (available as an optional cultivar name as there are many plants in that parent population that do not fit the description?) based on an initial description and limited illustration and has been maintained by myself while trying to resolve the issues in my own mind. It has been kept alive for me by populations at KomseRante and Kruisrivier that I am about to further explore after writing this particular piece, and that will be a separate chapter.

I cannot say that I have resolved the entire complex puzzle but these populations validate the decision reached with Gerhard that it “feels” right to really include ‘splendens’ with H. mirabilis rather than with H. pygmaea. This is where the actual relation of H. retusa and ‘turgida’ takes on another dimension similar to the H. mutica situation to the west where it is confounded by H. mirabilis.

The most significant population is the last noted one viz MBB7770. Not only are the plants larger than in other populations they also manifest the general pattern in Haworthia of “flow”. They resemble true ‘splendens’ that much more than the other populations because they are also geographically closer. Another oddity is their occurrence in the pure ferricrete at the top of the inselberg that I discussed under H. retusa. The most extraordinary thing is that this population shares habitat with H. retusa and while I cannot say there are hybrids, it is evident from some of the plants that hybridization may well have occurred despite the big differences in flowering times. ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 6:- Haworthia floribunda

Again this piece is written against the background of a detailed discussion in Haworthia UpdateVol. 2. Again I am not able to say the situation is fully comprehensible and neither do I want to encourage the daffy view that nature is just too much for us all. It is really curious that this species is woven into the fabric of H. mirabilis and also into that of H. chloracantha, H. parksiana and H. variegata. New finds have not clarified the picture so much as added another dimension to an extraordinary display. Not that H. floribunda is a spectacular species. In the field it can be extraordinarily cryptic and obscure while in cultivation it is an unlikely favourite. I do not want to repeat what I have already written while I hope that this will not contradict that either. H. floribunda seems to occupy a clear niche along the base of the mountains between Albertinia in the east and Swellendam in the west. It occurs as discrete from any other species although hybrids with both H. retusa and H. mirabilis do occur. South and west of Heidelberg it seems to lose its identity within H. mirabilis and then emerges briefly in a limited area near the Potberg in the southwest in a ‘mirabilis’ context as well as in H. variegata context. At Klipfontein farm at the western end of the Potberg it seems to be recognizable in relatively the same form as the very original description. But let us look at new information.

1. MBB7722 H. floribunda ‘major’. Appelbos. This is just west of Swellendam and we came across this locality while trying to confirm a very old record of the form ‘dentata’ once brought to me from Buffeljagts very nearby. The plants are quite large and have a clear green colour quite unlike the normal dark green or purplish hue of ‘typical’ floribunda. It should not be lost to the reader that this same colour difference characterizes the difference between H. retusa and H. mirabilis. Or that both colour variation is apparent in H. mirabilis ‘paradoxa’. Kobus Venter found a similar population northwest of Swellendam and further so than my rather poorly noted collection of proliferous dark plants with predominantly pointed leaves. In fact this population is hidden in its citation in my Revision under H. variegata. This will perturb those readers who are imprisoned in the paradigm of rigid similarities that define species. The Appelbos plants generally have the straight acuminate leaves that H. variegata has, but before arguing the issue and without actually properly looking at the whole H. variegata milieu, here are two connected records …

2. MBB7738 H. floribunda ‘major’. Swellendam. These plants were in fact small when first collected and in cultivation grew so large that I coined the name ‘major’ for them.They do still exist in a very small and disturbed area close to gum trees but curiously in moss free of leaf litter. I did also find them a little further away in a more grassy area where they are/were more typically small and dark coloured. I should note that I also recorded this ’dentata’-like version within the Bontebok Park close to where H. mirabilis occurs and I am still committed to again finding that population in the light of this new material.

3.MBB7774 H. floribunda ‘major’. Swellendam. We were concerned about the disappearance of an interesting form of H. minima from the area and in extending our search for plants came across H. floribunda in gumtree leaf litter about 400m east of the previous H. floribunda population. At first glance I did a double-take and then another because I actually thought I was looking at a slender form of H. marginata as occurs at Drew. The plants we saw were really large forms of H. floribunda with pointed leaves exceeding 100mm in length. They were quite proliferous and not all nearly as big as the first surprise ones. We also located smaller plants in numbers on the opposite side of the road also under gumtrees.

4. MBB7708 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. Goedverwagting. Apart from the Buffeljagts and Bontebok Park records there is an inexplicable hiatus in the appearance of the species west of Heidelberg. This is probably simply due to inadequate exploration that these new records now expose. It is quite evident that in the general area north of an imaginary line connecting Swellendam and Albertinia, H. floribunda does occur independently and in near company of H. mirabilis and the latter invariably in the form of ‘atrofusca’. This Goedverwagting record fills this gap as an association with ’atrofusca’ that pushes southwards.

5. JDV93/58 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. RoseInnis Drive; JDV93/56 do. Plattekop; MBB7760 do. Witkleikop; MBB7764 do. NW Platkop; MBB7767 do. Plaatjieskop. Being so cryptic may be a reason for the non-record of this species. It is associated with the ferricrete inselbergs and has the really curious association with H. mirabilis already remarked upon. In these four records, three of which are new, the plants occur independently of other Haworthia species and there is no obvious habitat preference that suggests why this is so. I also think that there is significance in which the characteristic rounded leaf tip is replicated especially in the juvenile leaves of H. mirabilis. The last cited record is the dramatic one. The plants are in very close association with H. retusa in two small geomorphologically different and adjacent sites, and we observed what seem to be reciprocal hybrids.

JDV93/58 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. RoseInnis Drive

JDV93/56 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. Plattekop.

MBB7760 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. Witkleikop.

MBB7764 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. NW Platkop.

MBB7767 H. floribunda ‘dentata’. Plaatjieskop.

Hybrid MBB7768 H. floribunda x retusa, Platjieskop

♦

Volume 5, Chapter 7:- Haworthia minima

There is not much to write about this less glamorous of plants. It is one of the Robustipedunculares. It is very widely distributed and even occurs north of the Langeberg Mountains in the Little Karoo – as does its sister species H. pumila. The pictures cover a huge range of variants from DeMond in the southwestern area to Riversdale. I found them all fascinating. Mostly so perhaps the very few large globose plants we saw at Kleinberg near Malgas (Diepkloof). But the plants at Koppies are really interesting because they were overlooked for so long. Koppies is the second known home of H. serrata (now H. rossouwii) and we came to know it also as a refuge for a small population of H. marginata. It was while we were investigating this that Hennie van Deventer casually pointed to plants of H. attenuata var caespitosa in his garden and said they were also on the farm. Because of our surprise and of course doubt, he took us to show the plants that he said he had not looked at nor thought of for 20 years – and there they were. A very small population of large dark coloured plants.

Also interesting were the very small solitary plants on the farm Sandfontein in the Slang River Valley. At Klipheuwel marginal to the coastal calcretes we also came across the species. Initially we saw only two plants while searching for ‘retusa-like’ plants. Failing to find anything else in a very severly grazed field we thought we would return to commiserate with the few H. minima we saw and enjoy the ambience we always feel in the presence of Haworthia. One can barely explain how cryptic these plants are and how easily they avoid detection. We found another 40 plants in the same area abut 10m diameter where we had found but two a short while earlier.

I found it very curious that in our very extensive exploration of the area east of Riversdale, that we saw neither H. minima nor H. marginata. Gasteria was also conspicuous by its absence and I remark on this because I do not think that taxonomy can remotely afford to ignore fundamental patterns in the general environment. ♦

MBB7737 H. minima, Koppies.

MBB7747 H. minima, Sandfontein.

MBB7757 H. minima, Klipheuwel.

MBBsn H. minima, Bontebok National Park.

MBBsn H. minima, Stoffelsrivier.

Others

Volume 5, Chapter 8:- An extension of H. rossouwii

What always comes to mind as I travel through the countryside is the realization of just how much there is to explore. It takes only an hour of driving from Cape Town to get to the start of Haworthia habitats from any of the three main routes inland. The roads do not always take in the best routes in respect of suitable or inviting habitats to explore, and besides there is the question of landownership and permission for access. In recent months my wife and I decided to really make an issue of new exploration and investing time and energy in contacting landowners and looking at places that we have ignored before because of access difficulties. The result has been a massive set of new finds in respect of populations not previously known to us. Having other interests such as in Drosanthemum and chameleons has also led us into places we might not have otherwise ventured.

This particular note arises from another chance find. Heidelberg is very rich as far as Haworthia is concerned and I have written quite a lot about the area or referred to populations there. It is a very important area for both H. retusa and H. mirabilis, as well as for H. floribunda and one assumes that the area has been fairly well explored. The Duiwenhoks River offers much suitable Haworthia habitat and I can count at least 30 populations along the drainage system that can be referred to those three species systems.

While checking on two populations of H. retusa ‘nigra’ (the informal way in which I now cite my own combination H. mutica var nigra derived from a G.G. Smith record south of Heidelberg), we took the opportunity to venture into a field from which we had on the previous occasion been excluded by the presence of ostriches. This was on the farm Diepkloof that I have cited as Morning Star because the two units are now farmed by the same owner and there is also confusion with farms on the east bank of the river also referred to as Diepkloof. The populations we looked at were of H. mirabilis and H. retusa ‘nigra’. The former appears to incorporate H. floribunda in all its populations down the Duiwenhoks River to as far as the change from Bokkeveld shale to Calcareous limestone near Vermaaklikheid. H. retusa var turgida occurs in various guises along the cliff habitats along the river while in non-riverine flatter areas H. retusa manifests.

We were specifically looking for H. mirabilis or H. retusa when my attention was drawn to an old flower stalk. There are a few bulb species that have a very similar dry inflorescence as Haworthia so I was a bit cautious when I bent closer to examine its source. With my search pattern set on the expected, I at first had difficulty focusing clearly on what was there before me – a small form of H. rossouwii (see MBB7803 Figs 1-9). We started looking wider and found a few plants under bushes until our eyes began to get the message as to what we should be looking for. To our amazement plants began to spring up all over the place among the dense pebbles.

Why Haworthia rossouwii? Firstly I have no sympathy with contending classifications that set out to do nothing more than weakly describe variation in the genus in terms of Latin binomials. My contention is that species are complex systems that need to be understood as highly variable elements that can respond to environmental differences and changes. H. rossouwii is already known to have an unusually wide distribution range as far as Southern Cape species were concerned. It is known from north northwest of Bredasdorp and is now known to us at 8 localities southwest of Heidelberg. Essie Esterhuyzen is reported to have found it at Voorstekop close to the N2 about 90km from the most southwestern population.

I relate “H. elizeae” to H. rossouwii. This was probably first recorded by Derek Tribble from the Bromberg mountain near Stormsvlei, about 40km north of the Bredasdorp populations of this species. There it is in sandstone, unlike the ferricrete and shale habitats the species is found in elsewhere. The Bromberg is also about 90km west of Morning Star. The similarity of the two populations is mostly in respect of size and the flowering time (without suggesting that this is inarguably evidence for sameness). The Morning Star plants are less proliferous in habitat at least, and this may simply be because slope and substrate so strongly relate to vegetative proliferation. The plants may get to as much as 50mm diameter under the protection of bushes, but in the exposed pebbles they average between 20 and 30mm. The colour seems to be darker green than the yellowish shade of the more general H. rossouwii but we saw plants in their stressed summer garb where there is a strong shade of purple in the plants. It will be interesting to see what the plants look like in the winter.

That this Morning Star population can so readily be allied with the Bromberg population, for me strengthens the view that the ‘systems’ approach to which I more strongly lean, is correct. What does worry we is that the formality of the nomenclatural systems, both botanical and horticultural, becomes very problematic. Essentially the infraspecific categories of subspecies, variety and forma are group categories derived in an era, and for plants, where less variability was known. In many species it has been relatively easy to add horticultural names and this may be because the flowers convey the interest and significance of difference. Where this is transferred to vegetative differences that are so dramatically affected by growing factors it will be very difficult to police. There is of course the additional problem of a taxonomy that is so personalized. Will anyone actually be able to establish when a published name is/was effectively a single plant description and hence a cultivar name as opposed to a group name? My view is that for the system to work, variability has to be limited and furthermore there is a complication where one now relies on vegetative characters that are so dependent on growing conditions – unlike the flowers of conventional horticultural cultivars. In Haworthia we may have an unusual problem in that many very similar looking species are involved and cultivars (single clones, bred or selected from nature) from different species may be very similar. I cannot personally see that anyone is going to successfully, meaningfully and usefully disentangle group and individual plant names. In H. rossouwii there might not be a problem as there is not a great deal of difference among the plants of the main body of populations that would excite the taxonomist. There is no doubt that there is enough variability to invite selection by the ardent grower who may develop a special interest in the species. The variant ‘elizeae’ and now ‘Morning Star’ (an informal and workable way of distinguishing the plants) may present problems in that the only way that they might be distinguished is if the collecting data remains attached, and with, any plant cultivated.

Acknowledgement

I am very grateful to Coetzee and Sarita Uys of Morning Star, to access Diepkloof, and to Gerhard Marx for useful comment and opinion. ♦

Volume 5, Chapter 9:- More on H. floribunda and H. mirabilis

In a recent set of articles published by the Haworthia Society I wrote the following in connection with H. floribunda… “MBB7738 H. floribunda ‘major’. Swellendam: These plants were in fact small when first collected and in cultivation grew so large that I coined the name ‘major’ for them. They do still exist in a very small and disturbed area close to gum trees but curiously in moss free of leaf litter. I did also find them a little further away in a more grassy area where they are/were more typically small and dark coloured. I should note that I also recorded this ’dentata’-like version within the Bontebok Park close to where H. mirabilis occurs and I am still committed to again finding that population in the light of this new material”.

In connection with H. mirabilis, I wrote … ”The Dankbaar plants are small versions of this and of course tie up with both older and newer (MBB7704) records for the Bontebok National Park. 2. MBB7743 H. mirabilis. Bontebok Park: Having written that, we did in fact locate still another population and of course it looked different as the area where it occurs had been recently burned and being on a northwest aspect the plants were very exposed and even more cryptic than usual.”

Since those finds and comments, we have again been back to the Bontebok Park. It is of course a large area of largely recent geological origins and therefore mostly ferricrete and riverine gravels. The lower lying areas are seasonally flooded. Being unsuitable for cropping or grazing, the area was handed over to the conservation cause (thank goodness for non-arable land). H. venosa occurs on the exposed Bokkeveld Shale cliffs along the Breede River, and H. minima is present in small scattered populations. H. marginata has virtually disappeared from thePark.

It is quite difficult to identify suitable Haworthia habitats as even in the seasonally flooded areas there is much gravel and consequently good drainage. It was in such a site that I seemed to remember seeing the record for H. floribunda cited in my Revision. Our searching has been very limited as it is quite difficult to explore the park with the restraints of accompanying rangers however willing or enthusiastic and knowledgeable. This is because I personally need mental space and physical freedom to walk where my intuition takes me. On this occasion we first went to an old entrance to the Park from the town where we thought H. marginata was first recorded. I was very disappointed to find that the hillside there had suffered the same mindless engineering fate that hit the gravel hills around Worcester. These were ”strip-mined” to obtain road materials. Of course this may have been necessary, but not the mindless extent of the surface scraping when some consideration for simply good housekeeping would have limited the desecration of the landscape and demanded some degree of resortaion.

We moved some way west to avoid the disturbed area and eventually found H. mirabilis (see MBB7805 Figs 1) about 500m east of the MBB6513 record of 1996 when I was writing the Revision, and illustrated elsewhere. That record came from a more distinct interface with the riverine shale while the new record was in more sandstone gravels from an old river bank. The plants were rather smaller than in 7704 with quite slender leaves which were also fairly toothed. There was little evidence of the flattened rounded leaf tips that characterize H. floribunda. We drove around the park trying while I was wracking my memory banks for where I might have seen H. floribunda so many years ago and eventually was drawn to where Tineke Kraaij had on a previous visit shown us H. mirabilis on a burnt zone (see MBB7704 Figs 2). These are new images to the original published ones, because after 6 months the plants had largely lost the burnt look but also being in flower they were far more visible. The leaves were more elongate and pointed than suggested by the photographs we took on the first visit and the plants reminded me very strongly of what I named as H. floribunda var. dentata. I also add here images for H. mirabilis (see MBB7744 Figs 3) from another population approximately midway between the previous two. Here the area had also been burnt as part of the management plan for the Park, but the plants themselves do not seem to have been affected possibly because there was a lighter fuel load that at the 7704 locality at the time of burning. The plants were more “maraisoid” and similar to the very first record of mine for this species in the Park (MBB6513). That collection I often noted among a set of 4 or more populations extending from Riversdale westwards to Riviersonderend that confounded any distinction between H. magnifica, H. maraisii and H. mirabilis.

All things considered, it seems highly unlikely that H. floribunda could possibly co-exist with H. mirabilis other than in the present known configuration where we have H. floribunda var major close to and north of the N1 highway near the town and inland, whereas H. mirabilis is further south. This geographic and presumed taxonomic relationship seems to hold at Heidelberg and Riversdale with some anomaly at Albertinia down the Gouritz river. This is where H. mirabilis is absent (with consideration for the retusa/pygmaea conundrum) and where H. chlrorocantha or H. variegata may be confounded in H. floribunda (or vice versa!). ♦

1. MBB7805 Bontebok National Park.

2. MBB7704 Bontebok National Park.

3. MBB7744 Bontebok National Park.

Volume 5, Chapter 10:- Haworthia ‘enigma’ and H. mutica var nigra

If the name “H.enigma” applies to the plant (or plants) from east of Riversdale at Komserante, it is a name that I really do not advise to be taken seriously from a botanical point of view. It is useful at population level and to demonstrate the nature of classification difficulties but it is a minor problem in so far as those difficulties extend. The plants were first shown to me by J. Dekenah on the same day that he also showed me ”H. magnifica” in the Nature Reserve just south of Riversdale that is less than 3km away. My impression then was that it was the same element even if it did look a bit different. The plants are quite large (to 70mm diameter), fairly tubercled and often with lines in the upper retused area of the leaf face. While I originally classified “H. maraisii” under “H. magnifica”, I later separated them because it seemed so incongruous to include all the variants of the western “H. maraisii” with the few populations of “H. magnifica” then known. Also, as Essie Esterhuizen pointed out, “H atrofusca” as a variant of “H. magnifica”, seemed to be more dominant than had been realized. There were several other complications largely due to ignorance. Since my revision I have done so much more exploration and turned up so much new material that I have been forced to the conclusion that there is really one main element involved and that is H. mirabilis. This is where I believe the Komserante plants belong and the difference from the Nature Reserve population is due to a degree of infusion of H. retusa.

I revisited the site with Kobus Venter many years ago but did not look at a reported second population higher up the hill, taking it to be a little different based on plants I saw in Kobus’ collection. What was on my mind while we were recently exploring the area further east to examine the possible connection of H. mirabilis “magnifica” to “splendens” (and which we confirmed), was the fact I had never seen Kobus’ plants from Kruis Rivier northeast of Riversdale other than in Kobus’ collection. The plants I saw were also generally more robust than “H. magnifica” and more evenly tubercled. Kobus kindly took me to that Kruis River locality and much to my surprise the plants were in flower late October (see JDV92/65 Figs1). This is quite wrong for H. mirabilis, which is essentially a summer flowering species. I later went again to explore Komserante more thoroughly and to look at both the “magnifica” populations to which I believe the name “H. enigma” has been applied. The populations are in fact no more than 75m apart and cannot be considered to be genetically discrete at all (see MBB7778 Figs 2, and MBB7779 Figs 3). While it is true that the habitats are slightly different, this is reflected in the plants that at the upper slope of the hillside are vegetatively more robust and even clump forming, while those lower down in a bushier grassier habitat tend to be solitary and more withdrawn into the soil. These plants flower in summer and it is evident to me that there must have been some genetic exchange with H. retusa that grows approximately 200m away on the same hillside.

1. JDV92/65 H. mirabilis Kruisrivier.

2. MBB7778 H. mirabilis. Komserante.

3. MBB7779 H. mirabilis. Komserante.

Habitat preferences are very strict and it is curious to observe that there are four small buttresses forming the western slope of the low hillside. On the northern one we have the two H. mirabilis populations. On the second is H. retusa ’geraldii’ (see MBB7780 Figs 4) that is very clump forming, the third has no haworthias and on the fourth is a less clump forming H. retusa that is often referred to as ‘fouchei’ (see MBB7781 Figs 5) because the leaves are slightly longer and more upright than in ’geraldii’. This is not quite correct. Mr. Dekenah showed me what he took to be the true H. retusa ‘fouchei’, further south off the hillside and along the stream at Komserante. This habitat has since been cleared for farmland. The plants were very large and the leaves considerably more erect than is the case for the plants on the hillside. Curiously H. minima is present on the first and last buttresses. Flowering time for these H. retusa is spring but we did see vicarious flowering in summer so that definitely it is possible and probably a regular occurrence for out-of-season flowering to occur with the possibility of hybridization. I noted such hybrids between H. retusa and H. mirabilis in our exploration further east from Riversdale and I did think some of the clones in the Komserante plants evidenced this as well.

4. MBB7780 H. retusa. Komserante.

5. MBB7781 H. retusa cf. ‘foucherii’. Komserante.

The reality is that the Kruisriver and Komserante “magnifica” may flower at different times, but they are vegetatively very similar indeed. I consider that they belong in the same system as H. mirabilis and this conservative view of “species” as systems is the most sensible way to interpret and understand the plants. The approach can be taken further, as I tried to do in an earlier article concerning H. mutica ‘nigra’. In that article I dealt with a whole series of populations in and around Heidelberg, to show that there are three main elements viz. H. retusa (including H. turgida), H. mirabilis (including H. magnifica) and H. floribunda. I did not deal specifically with, nor resolve, the issue of H. mutica var nigra. I also noted populations along the lower Duiwenhoks river and suggested that H. floribunda is absorbed into H. mirabilis virtually south of the N2 east west highway, re-emerging on the northwestern corner of the Potberg in the south.

My most recent exploration was to check the flowering times of the original population of H. mutica var nigra at its origin at Kransriviermond and what I assumed to be the same thing on rather limited examination further north at Morning Star. Both these populations are along the Duiwenhoks river southeast of Heidelberg and in a continuum of four populations of H. retusa extending from just east of Heidelberg to still further east at an eastern Diepkloof locality (I think it has been referred to as Droekloof and Droerivier too, and the name ‘chromatica’ attached to the plants – see MBB7794 Figs 6). Less than 10km away is a population of H. retusa at Pienaarsriver (see MBB7776 figs in Chapter 3) that is very near to the whole array of populations of Kiewietskraal that I discussed in my writings about H. mutica var nigra. Two of those were distinctly H. retusa and so is the Pienaarsriver population that is different in that the plants are mostly quite dark in colour.

6. MBB7794 h. retusa ‘chromatica’. SE Heidelberg.