56. Haworthia venosa (Lam.) Haw., Revis. :51(1821). Bayer :166(1976). Scott, Cact.Succ.J(U.S.) 50:74(1978). Bayer :76(1982). Scott :35(1985). Aloe venosa Lam. Encycl. 1:89(1873). Type: icon, 80:t29, Commelin, Prael.Bot. (1703). Epitype (B&M): Swellendam, Bayer 168 (NBG): Aloe tricolor Haw., Trans.Linn.Soc. 7:25(1804). Type: as for H. venosa: H. recurva Haw. Syn.Pl.Succ. :94(1812). Haw., Revis. :51(1821). Aloe recurva Haw., Trans.Linn.Soc. 7:10(1804). Simms Bot.Mag. :t.1353(1811). Salm Dyck, Monogr. 7:f3(1836). Type: Cape, Masson. Not preserved. Neotype (designated here): icon, f3, Salm Dyck loc.cit.: H. distincta N.E. Brown, Gard.Chron. 6:130(1876). Type: Cape, Graaff Reinet, Bolus (K): H. venosa var. oertendahlii Hjelmquist in Bot.Notiser :233(1943). Type: Not known.

venosa: veined.

Rosette usually stemless, slowly proliferous by off-set or stolons, to 30mm tall. Leaves to 100 X 15mm, spreading to recurved, ovate-deltoid, upper surfaces smooth reticulate, lower surfaces usually slightly scabrid. Inflorescence sparsely branched, lax. Flowers tepals fused, tube straight, lower inner tepals revolute.

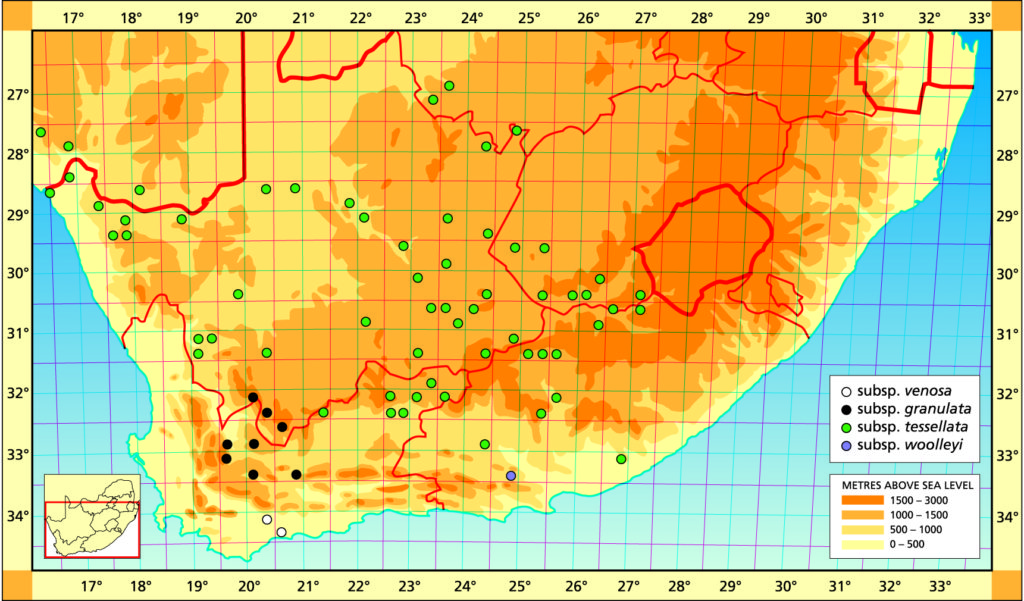

1982 – Originally the writer concluded that the name ‘recurva’ should be applied to what was generally known as H. tessellata. Scott (1978) insists on recognising three discrete species in this context and rejects the name ‘recurva’ as insufficiently known. After propagating H. venosa ssp. venosa from seed and seeing the extraordinary resemblance of the seedlings to the illustration in Simms Botanical Magazine of H. recurva, the writer is prepared to accept Salm‑Dyck’s statement that H. recurva was in fact grown from seed of H. venosa. The writer cannot accept Scott’s arguments regarding the status of the three subspecies listed above. Firstly the ssp. granulata is not confined to Verlatenkloof. It occurs at various points in the Ceres Karoo and there is a considerable variation in caulescence, leaf markings, and growth form. These variants do thoroughly confuse the issue as it is impossible to lay down definite criteria to consistently separate the subspecies. The ssp. venosa occurs in the Breede river valley and the variation here is also great. In the northern population the plants may have leaves up to 120mm long whereas a population (since destroyed) has been observed in the south with leaves less than 30mm long. In the field the leaves of the plants are invariably erect, whereas in cultivation they tend to recurve. The ssp. tessellata is extremely widespread occurring in South West Africa, the southern Orange Free State and at high altitudes near New England and Barkly East in the north‑eastern Cape. There is no cytological evidence available to suggest that the subspecies are discrete. Most chromosome counts are for ssp. tessellata, which does include polyploids, one count is available for ssp. venosa and none for ssp. granulata. Recent chromosome counts by Brandham (unpublished), confirm that normal diploids occur in all three subspecies. There is such a grey area of indeterminate forms that it is considered wiser to adopt a concept of subspecies for this group. The essential differences are that in ssp. venosa, the leaf surfaces are obscurely or lightly reticulate on the leaf faces, in ssp. tessellata the reticulation is pronounced, and in ssp. granulata the plants are caulescent and the leaf faces both scabrous and obscurely reticulate. Cultivation does not pose any particular problems. The ssp. granulata is from one of the driest areas in South Africa bordering on the winter rainfall area. It is very slow growing and also slowly proliferous by off‑sets. The ssp. venosa occurs in a dry area of the winter rainfall area and, while acaulescent, does form small clumps. Ssp. tessellata is very variable. It occurs primarily in the summer rainfall area and may be vigorously proliferous and also stoloniferous, or only slowly proliferous by offsets.

1999 – No changes are suggested here except to concede to repeated suggestions that H. woolleyi also be included in this species. There is an interesting record of Dr J. Muir of Riversdale from the Albertinia area which suggests that the ssp. venosa occurs in the Gouritz River valley. Scott considers that H. distincta did not originate from Graaff- Reinet as N.E. Brown maintained. This may be correct but it is rather ironic that the pressure to include ssp. venosa and ssp. tessellata under one species arose from repeated comments on the similarity of forms of the latter at Graaff-Reinet to the Breede River subspecies.

a. ssp. venosa.

Distribution: 3420 (Bredasdorp): Swellendam (‑AB), Bayer 168 (NBG); Bontebok Park (-AB), Bayer 3453 (NBG); Breede River (-AB), Fouche 60 (PRE); Malgas (-BC), Bayer 2670 (NBG).

Inadequately located: Swellendam, Theunissen (BOL); Albertinia, Muir (BOL).

Haworthia venosa ssp. venosa JDV97/150 southwest of Swellendam. Strangely isolated along the Breede River, although there isa specimen to indicate also the Gouritz River.

b. ssp. granulata (Marl.) Bayer :120(1976). Bayer :120(1976). H. granulata Marl., Trans.R.Soc.S.Afr. 2:39(1910). Scott, Cact.Succ. J(U.S.) 50:74(1978). Scott :9(1985). Type: Cape, Verlatenkloof, Marloth 4217 (BOL).

granulata: granulate.

This subspecies occurs virtually around the perimeter of the dry Ceres Karoo both in the higher rocky mountainous areas as well as on the flats among spiny Mesembryanthemaceae. It is usually caulescent and the stemless forms seem to be more scabrid.

Distribution: 3219 (Wuppertal): Skitterykloof (-DC), Bayer 4669 (NBG). 3319 (Worcester): N. Karooport (-BA), Hall in NBG827/54. 3220 (Sutherland): Ganagas Pass (-AA), Bruyns 274 (NBG). Ouberg Pass (-AD), Bruyns 2750 (BOL); Bantamsfontein (-CC), Bayer 5750 (NBG); Verlatenkloof (‑DA), Marloth 4217, 9632 (BOL), Scott 2200 (PRE), Hall 3168 (NBG), Stayner in KG309/68 (NBG); 60km N. Matjiesfontein (-DA), Scott 2201 (PRE). 3320 (Montagu): Touwsriver, Avondrust (-AC), Bayer 4668 (NBG); Witbergsrivier (-BD), Joffe 964 (PRE).

Inadequately located: Roggeveld, Logan (BOL); Wakloof (-BB), Hardy 2467 (PRE).

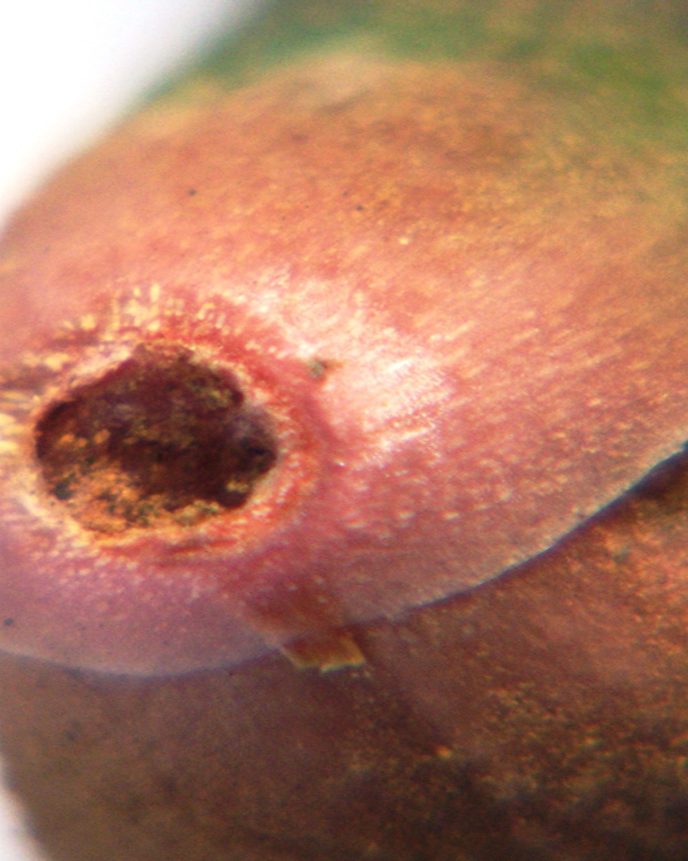

Haworthia venosa ssp. granulata JDV88/41 Ouber Pass. Widely distributed about the Ceres or Tanqua Karoo.

Haworthia venosa ssp. granulata JDV87/163 Ouberg Pass. Tall erect stems which cluster.

Haworthia venosa ssp. granulata JDV 88/38 west of Ouberg Pass. Well protected under bushes.

c. ssp. tessellata (Haw.) Bayer. Bayer :149 (1976). Bayer :76 (1982). H. tessellata Haw., Phil.Mag. 44:300 (1824). Scott, Cact.Succ.J. (U.S.) 50:74(1978). Scott :37(1985). Aloe tessellata (Haw.) Roem.et Schultes, Syst.Veg. 7:653 (1829). Salm Dyck, Monogr. 8:t1 (1836). Lecotype (Scott, 1985): icon (K): H. parva Haw., Phil.Mag. 44:301 (1824). H. tessellata var. parva (Haw.) Baker, JLinn.Soc.Bot. 18:211(1880). Aloe parva Roem.et Schultes, Syst.Veg. 7:763(1829). Salm Dyck, Monogr. 8:t2 (1836). Type: Not preserved. Neotype (designated here): Icon. :t2 Salm Dyck, Monogr.: H. tessellata var. inflexa Baker JLinn.Soc.Bot. 18:211 (1880). Type: ex hort, Kew. Not preserved: H. engleri Dint., Neu.Pfl.D.S.W.Afr. :31(1914). H. tessellata var. engleri (Dint.) V.Poelln., Feddes Repert.Spec.Nov. 44:202(1938). Type: S.W.Africa, Ussis-Schulucht, Engler in Dinter 3156: H. pseudotessellata V.Poelln., Feddes Repert.Spec.Nov. 27:133(1929). Type: Cape, Kruidfontein Rail, Mrs van der Bijl. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. tuberculata V.Poelln., Cact.Succ.J(U.S.).5:33(1936). Type: Cape, DeRust, Mrs Helm. Not preserved: H. minutissima V.Poelln., Des.Pl.Life 11:193 (1939). H. tessellata var. minutissima (V.Poelln.) Viveiros (1949). Type: Cape, Cradock, Fouche in Triebn. 1212. Not preserved: Neotype (B&M) icon, Des.Pl.Life 10:193 (1939): H. tessellata var. elongata Van Woerden, Succ. 22:37 (1940). Type: Namibia, Pevelberg, Graesner in Dresden 2205. Not preserved: Lectotype (B&M): icon in Succ:38 H. tessellata var. simplex Resende et V.Poelln., Broteria 11:49(1942). Type: ex hort Coimbra. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. stepheneana Resende ibid. :50. Type: Cape. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. luisierii Resende ibid. :51. Type: Cape, Queenstown, Triebn. 1207. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. palhinhiae Resende ibid. :51. Type: ex hort Dahlem. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. velutina Resende ibid. :52. Type: ex hort Hamburg. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. coriacea Resende ibid. :52. Type: Cape, Port Elizabeth, Long. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. coriacea fa longior Resende ibid. Type: Cape, Long. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. coriacea fa brevior idem. :53. Type: Cape, Long. Not preserved: H. tessellata var. obesa Resende ibid. 54. Type: ex hort Dahlem. Not preserved.: H. venosa subsp. recurva (Haw.) sensu Bayer :149 (1976).

tessellata: square patterned.

This is one of the most widespread and also abundant of the haworthias. It is extremely variable, which is usually the case with any of the less localised species. Motohashi et al. have examined chromosome numbers in this species and found polyploidy to be common. Hexaploids and octaploids appear to dominate the northeast, while tetraploids do so in the northwest and southeast. The number of chromosomes does not materially affect the appearance of the plants.

Distribution: 2623 (Vryburg): Vryburg (-DC), Vermeulen in KG108/60 (NBG). 2716 (Rosh Pinah): Schwarzekuppe, Aurus (-CB), Bruyns 3198 (NBG); Namuskluft (-DD), Bruyns 3926 (BOL), Bruyns 3171 (NBG). 2723 (Kuruman): Matlaring River (-AB), Acocks 2510 (BOL,PRE). 2724 (Taung): Buxton (-DB), Brueckner 1207 (PRE); Klein Boetsap (-CD), Pocock (BOL). 2816 (Alexander Bay): Hellskloof (-BD), Leighton 2333 (BOL). Augrabies (-CB), Marloth 12525 (PRE). 2817 (Vioolsdrift): Helskloof (-CD), Smith 6814 (NBG); NE. Eksteenfontein (-CD), Littlewood in KG955/62 (NBG); Kouefontein (-CD), Bayer 1661 (NBG). 2818 (Witputz): (-CA), Smith 7506 (NBG). 2820 (Aughrabies): Aughrabies (-CB), Leipoldt (BOL); Kakamas (-DB), Fuller 134 (BOL). 2821 (Upington): Wegdraai (-DD), Smith 2342 (NBG). 2917 (Springbok): Gunhill, Anenous (-BA), Barker 8966 (NBG); Arabees (-BB), Smith 1680, 1686 (NBG); (-BC), Meyer (BOL); Kinderle (-BD), Smith 7276a, 7277 (NBG). 2918(Aggenys): Aggenys (-BB), Oliver, Tolken & Venter 55 (PRE). 2922 (Prieska): Marydale (-AA), Smith 1677 (NBG); Prieska (-DB), Bryant 576 (PRE). 2923 (Douglas): Mazelsfontein (-BA), (BOL). 3.6km NW. Campbell (-DC), Leistner 902 (PRE). 2924 (Luckhoff): Belmont (-AD), Lang 6854 (PRE); (-DB), Freund 44 (BOL). 2925 (Fauresmith): Jagersfontein (-CB), Smith 7486 (NBG); Koppies (-CB), Henrici 1956 (PRE); Veld Reserve (-CB), Marloth 13104 (PRE); Veld Reserve (-CB), C.A.Smith 536 (PRE); Veld Reserve (-CB), C.A. Smith 5208 (PRE); Koppie (-CB), Verdoorn 2372 (PRE). 3019 (Loeriesfontein): Jaagvlakte (-BD), Bruyns 3037 (BOL). 3022 (Carnarvon): Vaalhoek (-CC), Bruyns 3034 (NBG). 3023(Britstown): Omdraaisvlei (-AA), Smith 2343 (NBG); Brakfontein (-CB), Smith 7280 (NBG); Twyfelhoek -DA), Bruyns 3021 (NBG); Vloekpoort (-DD), Bruyns 3018 (NBG). 3024 (Philipstown): (-AD), Battenhauser (BOL); De Aar (-CA), C.A. Smith 2809 (PRE). 3025 (Colesburg): Philipolis (-AD), Smith 7478 (NBG); Bethulie (-BD), Smith 5182 (NBG). 3026 (Aliwal North): Kraairivier (-AB), Smith 6063 (NBG); Tussen Riviere (-AC), Roberts 5570 (PRE); Murraysville (-CD), Smith 7412 (NBG); Doctors Drift (-DA), Gerstner 58 (PRE). 3027 (Zastron): Vegkop 11km W. Zastron (-AC), Fouche in PRE 34871; Karnmelksrivier (-CA), Smith 5669 (NBG). 3119 (Calvinia): Ezelskop (-AA), Bruyns 6841 (NBG); Koppieskraal (-AB), Pearson 4887 (BOL); Vanrhyns Pass (-AC), Bolus 1206/32 (NBG), Smith 3943 (NBG). 3120(Williston): Hamberg, Syter (-AD), Branch 333 (NBG). 3123(Richmond): Victoria West (-AC), James in NBG925/13 (BOL); Nuwerus (-CD), Bayer 4677 (NBG). 3124(Hanover): Cypherwater (-AD), Bruyns 3007 (BOL); Tweedale, Noupoort (-BB), Branch 38 (NBG). 3125 (Steynsburg): Flouker (-AC), Branch 39 (NBG); Rooispruit (-AD), Smith 6056 (NBG); Schoombie (-AD), Smith 3639 (NBG); Thebus (‑BC), Latimer in NBG 69408, Smith 610, 3636, 3637 (NBG). 3221 (Merweville): Aarfontein (-AD), Bruyns 6276b (BOL). 3222 (Beaufort West): Karoo Park (-BA), Branch 34 (NBG); E. Molteno Pass (-BC), Bayer 2372 (NBG); Road to Loxton (-BC), Scott 350 (PRE); Stolshoek (-BD), Bruyns 3383 (BOL). 3223 (Rietbron): Nelspoort (-AA), Bayer 2385 (NBG), Stayner in KG767/60 (NBG); Redcliffe (-BA), Bruyns 7055 (BOL). 3224 (Graaff-Reinet): Aberdeen Road (-CD), C.A. Smith in PRE 8888. 3225 (Somerset East): Mt. Zebra Park (-AD), Branch 33, 40 (NBG); Halesowen (-BA), Bayer 4667 (NBG), Reynolds in NBG2552/33 (NBG), Smith 2240 (NBG). 3326 (Grahamstown): Committees (-BB), Dyer 2172 (PRE).

Inadequately located: Sunnyside, Beaufort West, Esterhuysen (BOL); Aliwal North, Reynolds 112, in NBG2399/32, in NBG 2401 (BOL); Graaff Reinet, Bolus 794 (BOL); Aberdeen, Ferguson (BOL); Ex hort., Van Nouhuys in PRE 34853 (PRE).

Haworthia venosa ssp. tessellata T.Visser sn. Upington. Very widely distributed and also variable. The leaf markings can be quite striking.

Haworthia venosa ssp. tessellata JDV97/61 east of Beaufort West. Can be very proliferous from stolons.

d. ssp. woolleyi (V.Poelln.) Bayer comb.nov. H. woolleyii V.Poelln., Feddes Repert.Spec.Nov. 42:269(1938). Bayer :168(1976). Bayer :79(1982). Scott :40(1985). Type: Cape, Springbokflats, Woolley in Long 440. Not preserved. Lectotype: icon (B).

woolleyi: after C.H.T. Woolley.

1982 – When evaluating species rarity, H. woolleyi is seldom called to mind. However, there are only two recorded instances of its ever having been collected. The writer’s own record is of a single large clump growing completely hidden within a spiny shrub on the northern face of a rocky outcrop. The relationship is obviously with H. venosa but it has many more leaves per rosette. These are inserted closely on the stem so that the plant form is very like that of say H. attenuata. The leaves are obscurely tesselate and also long and slender (up to 60mm long.). Cultivation appears to be difficult and growth extraordinarily slow. Although a clump‑forming species, offsetting is very slow and it is as quick to propagate this species from seed as from offset.

1999 – There are still very few records for this subspecies and this may either reflect its rarity or the general lack of systematic and conscientious recording. There is no doubt that many collectors have roamed the area to the chagrin and annoyance of the local farmers. The population known to me was very sound up to at least 1980 when I recorded at least six large proliferous clones. Soon after this an attempt was made to protect the area by changing the fence-lines. This appears to have been a total disaster as the new fence either placed the plants within the farmer’s grazing camp, or concentrated stock against the fence just where the plants existed. Whoever may have been so cloddishly stupid to have been able and willing to eradicate (by collecting) the proliferous clones that I knew, is inconsequential now. The moving of the fence, coupled with overgrazing (using the term to mean exerting grazing pressure to the extent that gross erosion ensues), or perhaps only the latter, has resulted in total destruction of the habitat. The site is overgrown with weedy Mesembryanthemaceae and Atriplex lindleyi. Also where there was a small but healthy number of H. sordida and some hybrids with H. woolleyi in a stable, vegetated ravine, there are now just erosion gullies and weeds.

Distribution: 3324 (Steytlerville): Springbok Flats (-BD), Woolley in NBG 1990/37 (BOL), Long 1442 (PRE); Kleinpoort (‑BD), Bayer 167 (NBG).

Haworthia venosa ssp. woolleyi JDV87/151 south of Kleinpoort. Fortunately many many seedlings were produced and there should be a good source of genetic material in collections.

Haworthia venosa ssp. woolleyi JDV90/68 south of Kleinpoort. The destruction of this, the only known habitat is a very sore point, involving a great deal of acrimony.