- Haworthia Update Vol. 11 – Table of Contents

- Still another view of Haworthia retusa and Haworthia mirabilis

- A sequel … Still another view of Haworthia retusa and Haworthia mirabilis

- Die Nekkies Haworthia – A further visit and updated information

- Haworthia maculata leaf tips, faces and backs

- A further report on Haworthia mirabilis in the Greyton area.

Category Archives: Update 11

Still another view of Haworthia retusa and Haworthia mirabilis

I recently wrote an essay on the situation between Haworthia retusa and Haworthia mirabilis at Komserante east of Riversdale. The essay was entitled “My view of names” and is posted on the HaworthiaUpdates.org web site. Etwin Aslander posted some pictures from what he called Kruisrivier. These caught my eye because they did not look like the plants I know from a place of the same name. My known population is JDV95/62 and generally these plants have the dark colour and rough surface texture of H. mirabilis. The issue is that they are spring flowering whereas H. mirabilis is generally considered and observed to be late summer flowering. Etwin indicated to me where he had found his plants and I duly went to look.

In the process I incidentally called on a well known H. retusa population at the Skietbaan locality south of Riversdale. There has been a dramatic turnabout in the appearances of these plants since I last looked there 2 years ago. Whereas there were then huge clones well above ground level, the plants were now again smaller and drawn into the ground. I experienced this dramatic shift in plant appearances just west of the Frehse Reserve many years ago when there were giant size plants as opposed to my first visit when the plants were really small and withdrawn.

Kobus accompanied Daphne and I to Kruisrivier where the owners Wilhelm and Mandi Zietsman were extremely helpful. They told us also of a neighbor, Gert van Rensburg, who had also seen the same plants on his farm to the west. Mandi accompanied us on a jaunt to find that farmer and failing that we explored north of the original Kruisrivier locality. There we found another population of plants as well as H. floribunda (see Set 1 MBB7998). These two species H. retusa and H. floribunda were occupying different habitat and spaced about 100m apart. The H. floribunda was numerous and rather smooth leaved as well as paler green in colour than I expect from that species. The H. retusa-like plants were much smoother in surface texture than the original known population and they were in bud (see Set 2 MBB7999). We went back to the older population just to confirm that they were in bud too as we expected. Just so and the buds were just emerging from the rosettes. The plants were generally smaller than they were at a previous visit (see set 3 JDV95/62).

We parted company with Mandi Zietsman, and went off westwards intended to explore the Klein Kruisrivier area that seemed to better fit Etwin’s site indicator. By good fortune we ran into Gert van Rensburg of Wegwysersrivier. He eyed us very suspiciously indeed and obviously very reluctant to show anyone the plants. However, he very kindly relented, took us to the spot and left us to freely photograph and explore (see set 4 MBB8000). The plants can be described as midway between the generally rougher surfaces of JDV95-62 and the smooth surfaces of MBB7999. What was more dramatic is that there were six flower spikes so that flowering is possible as early as July 6th.

We returned via another route regretting leaving distant habitat unexplored. But we did find another population of H. floribunda, a little more toothed and perhaps brighter green than at Kruisrivier.

I also note that I long ago confirmed Smith’s record for H. retusa ‘turgida’ at Klein Kruisrivier in the upper Wegwysersrivier Gorge. This is the small spinose proliferous version known elsewhere from the Langeberg Mts.

Digesting this new information is a bit difficult in view of the very opposed views of what names mean and how they should be applied. Taking all the populations that I have explored and written about, my perspective is further to a view expressed in Haworthia Update 7. This is that H. retusa and H. mirabilis are uncomfortably close. The only thing that appears to separate them is the yellowish green and smooth tendency in H. retusa and the darkish green and surface rough tendency in H. mirabilis. Further to that is of course the question of spring flowering versus late summer flowering. But I have already reported several case of hybridization across this divide as well as the Komserante situation. Here we now have plants in three populations that occupy middle ground and one of these populations has a significant degree of a winter flowering capacity. The identification should perhaps utilize the chemical equilibrium symbol. This is not quite it “↔” as the better symbol comprises halved arrows pointing in opposite directions.

I wish to add that in the case of plants I attribute to H. ‘turgida’ at Towerlands, I commented on the very real possibility of a close connection to H. emelyae. There is also evidence for this elsewhere. I use the name ‘turgida’ like this because of the uncertainty of it really being H. retusa var. turgida or perhaps H. pygmaea.

My experience in other situations viz. H. limifolia, H. herbacea/H. reticulata, H. arachnoidea/H. mucronata, H. cymbiformis/H. cooperi, Kiewietsvlakte etc. all suggests to me that the view of species is grossly distorted in the splitter direction. It is clear to me, if to no one else, that H. retusa and H. mirabilis form a very cohesive entity with ramifying oddities the length and breadth of the distribution range. I do not cover this issue here, but there is the added complication of the involvement of H. floribunda. It seems to be very discrete in most places, whereas at others it seems to get lost mainly (only?) in H. mirabilis. This may be because the introgression is favoured by the same flowering season. H. retusa and H. mirabilis are drifted apart by the difference in flowering season but it is by no means anything more than a general observation.

I have added the images of the available flowers as well as that of a bud to show the flared fishtail bud-tip that the southern Cape species tend to have. The flowers are variable and it is difficult to make a statement that characterizes them i.e. no composite image forms.

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge Etwin Aslander’s input. Wilhelm and Mandi Zietsman were extremely helpful. Gert van Rensburg was surprisingly well informed about the plants too and very generous in his attitude to us. Part of the pleasure of field work is meeting people like this.

Set 1. MBB7998 H. floribunda Kruisrivier

Set 2. MBB7999 H. retusa Kruisrivier

Set 3. JDV92/65 H. retusa Kruisrivier

Set 4. MBB8000 H. retusa Wegwyserivier

MBB8000 flower faces

MBB8000 flower profiles

MBB8000 flower bud

Addendum

To demonstrate the problem of similar looking plants that appear in different populations, I take 3 plants from the original Kruisrivier population (JDV92/65) see figs 1 to 3. Fig. 1 is obviously a mirabiloid plant and if this population flowered in late summer it would probably be identified as H. mirabilis. The figs 2 and 3 are more retusoid. I leave out plants from the newer Kruisrivier population (MBB7999) because none of the plants have the rougher mirabiloid leaf surfaces. I add a Wegwysersrivier (fig. 4 MBB8000) plant that is again mirabiloid and like Fig. 1 except that it appears to be a spring flowering population with a significant number of plants in flower in early July. From there I take a plant from Komserante (MBB7779) that flowers in late summer but is apparently generally hybrid with H. retusa. Moving eastwards from Riversdale and impinging on H. mirabilis splendens, I show a plant MBB7762 from Platkop (fig. 6) where both H. mirabilis and H. retusa occur with occasional hybrids. Fig. 7 is MBB7818 H. mirabilis Windsor SE Riversdale, where the plants frequently have a frosted appearance because of minute surface spines.

There is a significant geographic jump with fig. 8 MBB7850 H. emelyae north of the Langeberg at Aasvoelvallei. This is a population that I have noted elsewhere that highlights the probable relationship of H. emelyae with the H. retusa turgida and pymaeaoid elements from Herbertsdale eastwards. Fig. 9 is a plant of MBB6666 Tradouw Pass that I recognize as a hybrid population H. mirabilisXretusa. Inland from there are several populations, MBB7899 is H. mirabilis, Heuningklip (fig. 10) and MBB7896 H. retusa nigra also Heuningklip (fig. 11). East of that are three populations of H. mirabilis, MBB7912 and MBB7913 Rietkuil and MBB7919 Van Reenens Crest (figs 12 to 14).

As only single plant comparisons, it seems fairly safe to say that, bar flowering time and figs 2 and 3, they are all similar. However, the variability in each of these populations is great and this has been reported elsewhere in the Update volumes. If one had to now take figs 2 and 3 and look for similarities in other populations, it would be very easy to demonstrate a complete gradation from what could be construed as typical H. mirabilis through to typical H. retusa through a large array of populations.

♦

A sequel … Still another view of Haworthia retusa and Haworthia mirabilis

It has long been my contention that there is no separation between Haworthia retusa and Haworthia turgida. It is one very variable system viz H. retusa, with a larger fairly non-proliferous plants tending to level areas and then smaller proliferous plants on steeper habitats. There is huge variability among members of any one population and of course much more between populations. Over and above this is the relationship of this apparently one single system, with H. mirabilis that is probably even more complex and varied. If one takes all the known populations and variants into consideration it become necessary to ask if H. retusa and H. mirabilis are also not just elements of one system, and one species. If all the considerations are summed and referral is made to vegetation and speciation drivers; what constitutes an area of endemism, then I am sure the answer will be “Yes”! What seems to have happened is a natural sequence. As sampling has progressed so has there been recognition of differences. The logical outcome is that sampling progression should lead to understanding and synthesis by reduction. Unfortunately there will be diehards that stay with the differences syndrome and cannot see the similarities.

There is surely no longer any doubt that Haworthia classification has been confounded. There are several factors. One is the historical one of sampling and naming. Sampling dates from the seventeenth century and description based on a few words and weak illustration. The second problem has been a nomenclatural system that revolves around the single types and assumes that departures from that still allow comfortable accommodation of all other departures (variants) under the primary name. The third problem is the absence of a species definition deriving from a lack of knowledge and hence understanding of what species are. The fourth problem is enthusiasts, writers, collectors, editors, reader etc. who generate and propagate within the confines of their own needs, limitations, knowledge and understanding. Too often they are not adequately informed to undertake something that really should be the task of professional botanists. Of course it is also true that professionals have not proved to be faultless either, as simply the lack of a species definition alone indicates.

From my personal point of view, I consider the sampling history and the nomenclatural constrictions of priority and automatic creation of type elements, among the main obstacles to a classification solution. Perhaps it is only secondary to the human factor where writers become anxious to establish their own opinions, based on who knows what, crowing from the top of a metaphorical farm dungheap. I have paid a lot of attention to an element that I name as H. retusa ‘nigra’. It is based on a very unrepresentative specimen from Kransriviermond where it seems as if it is a product of hybridization between H. retusa and H. mirabilis. But this situation, and the name, is inextricably involved in a series of populations grouped in areas like Van Reenens Crest (Swellendam), Klip River (W Heidelberg) and Kiewietsvlakte (W Riversdale). These populations do not seem to figure in any earlier exploration and if looked at objectively may now perhaps be seen as the mother lode from which H. retusa, H. mirabilis, H. pygmaea, H. mutica and even H. emelyae as species may emerge. The reality is that all these may not in fact even be discrete species.

In the forerunning article I discussed some new populations at Kruisrivier northeast of Riversdale and where they occur along the Kruis River. This river partially follows the interface of the Cape Sandstone Fold Mountains in an east/west direction and the situation is replicated to some measure elsewhere between Worcester and George. Most relevant is the similarity of the Kruis River valley and its south banks to the situation along the Klipriver west of Heidelberg. But it is not in the scope of this discussion to cover that now and I would in any case need to research the geology of both areas to do so. I will just present images to cover firstly the area, then to allow creation of a composite image of what the small sandstone H. retusa looks like, then images from just two populations of H. retusa to show how shadowy our image of this species is; and then I will show the images of plants from five points down a distance of about 4km along the south bank of the Kruis River to a point south and west of the better known Kruisrivier plants.

Setting the scene.

The Kruis River Valley is slightly east of north from Riversdale and the Kruis River is a headwater of the Goukou River that enters the sea at Stilbay. The views I have (figs. 1-4) are of a satellite image of the Valley from where the Kruis River exits the Langeberg Range to where it joins the Goukou. Three images are from the south bank looking northwest and northeast. The area is very heavily impacted by alien vegetation. The grazing animals are mainly cattle (beed and dairy) and hoof impact on the slopes is severe. The underlying shale along the south bank is not exposed and there is both boulder deposit, river alluvium and even some marine terrace in evidence. Nevertheless the area is not so dramatically varied geologically as is the area around Heidelberg to the west. Hence the transitions and interactions between species and their variants are both similar but very different. The initial conditions will be very different too.

The populations.

The first three sets are to briefly review H. retusa. The general perception of H. retusa is very restrictive and similarly the case with what was H. turgida. I consider them together. Nevertheless I have to sympathize with the splitter approach because I have to make a concession for the sake of discussion. Thus…

Set 1 MBB7895 H. retusa ‘caespitosa’, Diepkloof, Heidelberg (figs 5-9).

I explored the upper Kruis River in early 1970 and found the small sandstone version of what was then recognised as H. caespitosa. Later seen as H. turgida, it is known at many places from the Tradouw Pass, north of Heidelberg, Garcia Pass and Kok’s peak. Small and very proliferous, its leaves are also quite spinose on margins and keel and also flecked with reticulate and longitudinal translucence. The summer coloration tends to reds and yellows. I do not have images of this actual form but show five from a population south of Heidelberg that is very similar. But it should not be assumed that the transitional flow in the Heideberg area equates that at Kruis River. The variants down the length of the Klip and Duiwenhoks Rivers is another profound story.

Set 2 MBB7758 H. retusa, Skietbaan, S Riversdale (figs 10-19 ).

I show images of this species very recently taken. This is because I do not think that as a species H. retusa is properly appreciated for all its variants. It is this reality that we are confronted with when considering populations as at Komserante and now Kruisrivier where there is an evidence that it cannot any longer be seen as completely removed from H. mirabilis.

If images 10a and b appear to be different from the rest of this wet, they should. They are plants from the same locality but they were taken 4 years ago when most of the plants were very much larger. They illustrate a very useful point – the plants do NOT necessarily look the same all of the time.

Set 3 MBB8010 H. retusa, 8km S Riversdale (figs 20-28 ).

Primarily one should consider surface roughness and colouration as main separators from H. mirabilis. Flowering time is the prime differentiator and this is what is now to be seen in another light.

Set 4 MBB8004 H. retusa↔mirabilis, Bloekombos, Kruisriver (figs 29-42).

Reference can perhaps be made to the three sets illustrated in the preceding article. Here is will just re-capitulate to say that there is some doubt in respect of plant appearance and colouration, to examine the view that the represent H. retusa or H. mirabilis. (I dismiss totally and absolutely the notion that a third species needs to be fabricated to accommodate differences impossible to itemize or catalogue across the range of variants within and between populations.) I do not think that the similarity of surface roughness to that of the H. mirabilis ‘atrofuscoids’ should be overlooked – even some of the leaves show the tendency to roundness at the ends. This particular population was in full flower at the end of July.

Subset 4 The flowers (figs 43-45). I do not see anything to distinguish these flowers from those photographed for the Wegwysersrivier population and given in the preceding article. It is difficult to imagine that the flowers may offer any distinctive features in the direction of difference that are not already offered by vegetative and geographic considerations. There may of course be direction towards similarity.

Set 4 H. retusa-mirabilis, MBB 8004 Bloekombos, Kruisriver – Subset 4a Flower profiles

Set 4 H. retusa-mirabilis, MBB8004 Bloekombos, Kruisriver – 45. Subset 4b Flower faces

Set 4 H. retusa-mirabilis, MBB8004 Bloekombos, Kruisriver – 45. Subset 4c

Set 5 MBB8003 H. retusa↔mirabilis, W Bloekombos, Kruisriver (figs 46-73).

Curiously this population was only in early bud although only a few hundred meters away from the preceding. I do think there is significant difference in the appearances of the plants with more translucence of narrower leaves. However, plants from this and the preceding population could very easily be said to identify with those in any of the H. mirabilis populations southeast, south and west of Riversdale. It is also obvious that there is a degree of similarity to the rougher plants of H. retusa illustrated in sets 2 and 3, and also to the Komserante H. retusa↔mirabilis plants.

Set 6 MBB8007 H. retusa↔mirabilis, 600m W Bloekombos, Kruisriver (figs 74-81).

The banks west of set 5 are less steep and the terrain not clearly differentiated into discrete habitats. Heavy cattle trampling would severely impact on plants. Nevertheless we did find a small colony and are confident more would be found if more time was spent searching. The area is quite extensive and we did not consider several north/south valleys that could well harbor plants. The same is true for quite large hinterland to the Kruis River Valley and Etwin Aslander’s plants, similar to the ones we saw, are surely present back there. This small colony reflects further transition to H. retusa ‘turgida’. The leaves are smoother and more translucent. There are some floral differences muted by the small sample and by the fact that these features such as the absence of frilled base to the bract and the presence of a short pedicel, are variations observed within populations elsewhere.

Set 7 MBB8008 H. retusa↔mirabilis, 1km W Bloekombos, Kruisriver (figs 82-83).

Also barely, registering as a population, these odd plants support the predicted presence of a direct transition from the Kruisriver mirabiloid-like H. retusa to the known sandstone forms of H. retusa ‘turgida’. Hoof action has severely impacted this area and it sems very probable that there was a larger population at some time or another. The slope militates against the solitary ground-level growth form of the more usual H. retusa but not steep or rocky enough to be home to the turgidoid cliff growing forms.

Set 8 MBB8005 H. retusa ‘turgida’, S Wegwysersrivier (figs 84-98).

The use of the equilibrium sign for the preceding is more informative than accurate. It reflects the problem of decision making where it is not clear if H. mirabilis is even in the area. This of course impacts on the situation further east when the reality of H. pygmaea and all its associated variants are brought into the picture. I am sure it is inarguable that we are now confronted with plants that are truly similar to H. retusa ‘turgida’. Curiously the flower is much the same as in MBB8003 and 8004 to the east but there is a difference in that the peduncles were softer and shorter than of plants to the east and suggesting the shorter lax habit of the cliff dwellers. The habitat is unlike the preceding in that the Tertiary deposit is more alluvial and the rock is more boulder-like. Trampling is still a severe problem. Note the two pictures of a H. retusaXfloribunda hybrid.

Set 9 MBB8006 H. floribunda, S Wegwysersrivier (figs 99-107).

The presence of this species is no surprise. It was quite abundant although slightly separated from where we found the H. retusa ‘turgida’. It depends on rocks for protection from trampling. This species of course generally flowers in late summer but once again here is a hybrid present with the other parent flowering a good 6 months later. This has been observed in several other places where these same two species occur in close association. [photo file names are mistakenly named MBB8005, they are in fact MBB8006 – ed.]

Conclusion

The product of this exploration was based on prediction and I would wish that cognizance was taken of the fact that this could and can be done. Using an aggregate or group category and a host of Latin binomials is not botany and obfuscates things. Perhaps to the benefit of traders, but certainly confusing to the collector who make wish to know more about plants than simply having a label.

Acknowledgement

I have already acknowledged the help of Wilhelm and Mandi Zietsman; and Gert and Lynette van Rensburg. We were now also assisted by Wessie Wessels, a retired airline pilot who owns the Bloekomsbos Farm. Kobus Venter came to see my pictures and I really value his interest and useful comment. I wish there was more similar interested and informed comment. ♦

Die Nekkies Haworthia – A further visit and updated information

Bruce Bayer has now been back to Die Nekkies and returns with more detail to add to the broader Haworthia maculata picture, and considerable detail for H. maculata at its home range located north of the Brandvlei Dam on a low range of hills named Die Nekkies. (See Haworthia Updates Volume 9, A myth corrected to – Haworthia maculata var. livida (Bayer) Bayer – and flowers ignored). These low hills extend for 10-12km east to west along the north shore of the Dam. They are geologically Witteberg Sandstone and H. maculata is not known off this formation except in the lower Hex River Pass where it is found in Table Mountain Sandstone. H. herbacea (and H. reticulata) are more abundant on the Dwyka Tillite, and on Bokkeveld and Ecca shales. The Wiiteberg is sandwiched between Bokkeveld Shale and Dwyka Tillite, and Ecca Shale of the Karoo System overlies Dwyka Tillite. Because of considerable faulting and folding the Cape Terrain is geologically and topographically very broken and there are a multitude of skeletal rocky habitats – the raw rock is very exposed and the surfaces are erosional. Haworthia are rarely found on depositional sites. The fact that there is also a stable and dependable winter rainfall also contributes greatly to the success of small succulents in situations that cannot maintain high biomass levels. This all drives home the fact that Darwin’s dictum that distribution is the lintel to understanding species is doubly true for Haworthia where morphological differences are minimal.

In Die Nekkies and Biomes and Haworthia maculata Haworthia Updates Volume 6, Chapter 6 Bruce Bayer explained and presented data in connection with the variation and distribution of what he considers to be the species Haworthia maculata over the whole range of its distribution. He long ago wrote explanations like this for H. reticulata and H. herbacea that are related species. Bayer has already shown that in genera like this within the very diverse Southern African system, simply do not resolve on the basis of simplified morphological characterization. The new data presented here, especially with the observations on the varied flowering time of H. maculata, shows that the view expressed, that H. retusa and H. mirabilis really form one integrated system, is true. This further underscores the view long ago held by Bayer that H. herbacea, H. reticulata and H. maculata are further extensions of that single system. Even the floral morphology points to this.

– Lawrence Loucka

[photographs and map by Bruce Bayer]

Populations:

Haworthia maculata – 7526, 8019, 8020, 8021, 8022, 8023, 8024, 8025, 8026, 8027.

Haworthia herbacea – 7995, 7996, 8012, 8014, 8015.

Transition Haworthia herbacea to Haworthia maculata 7996

Haworthia pubescens – 8011.

Weak transition Haworthia maculata to Haworthia pubescens – 7997.

Strong transition Haworthia maculata to Haworthia pubescens – 8002.

7996 as H. herbacea is very close to 8020 that is H. maculata and the nature of the plants at 8020 is that the population is transitional to herbacea too. In fact the same is almost true for 7996.

Haworthia maculata MBB7526, Die Nekkies

What a difference a few weeks can make … above photos taken November 1, 2012.

Below were taken December 8th.

And an interesting variant…

MBB8019 – Haworthia maculata, Yacht Club Gate, Brandvlei

Haworthia maculata MBB8020, Die Nekkies, east end

Haworthia maculata MBB8021, Die Nekkies, west end

Haworthia pumila also near by.

Haworthia maculata MBB8022, Die Nekkies

Haworthia maculata MBB8023, Die Nekkies

Haworthia maculata MBB8024, Die Nekkies

Haworthia maculata MBB8025, Die Nekkies

Long thin leaves.

Haworthia maculata MBB8026, Die Nekkies

View west from 8026.

Haworthia maculata MBB8027, Die Nekkies

♦

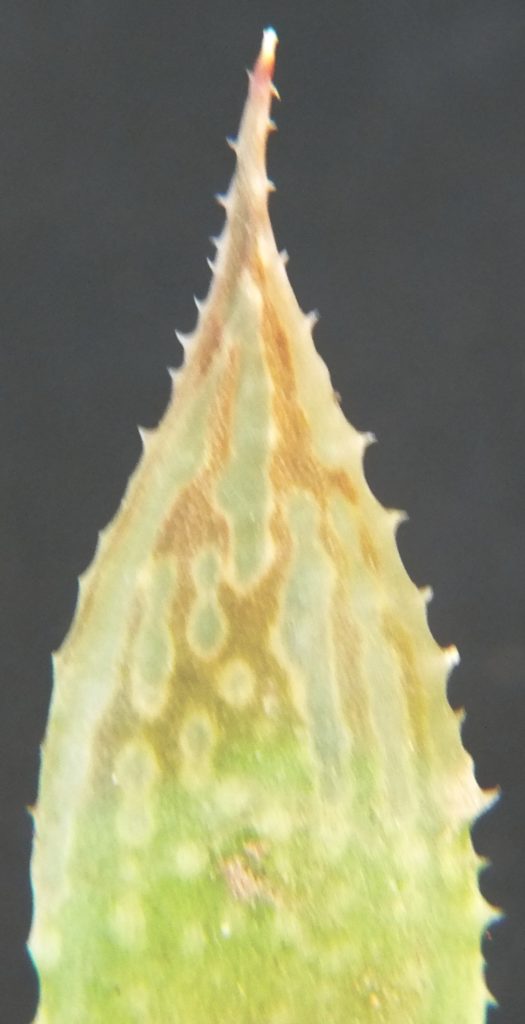

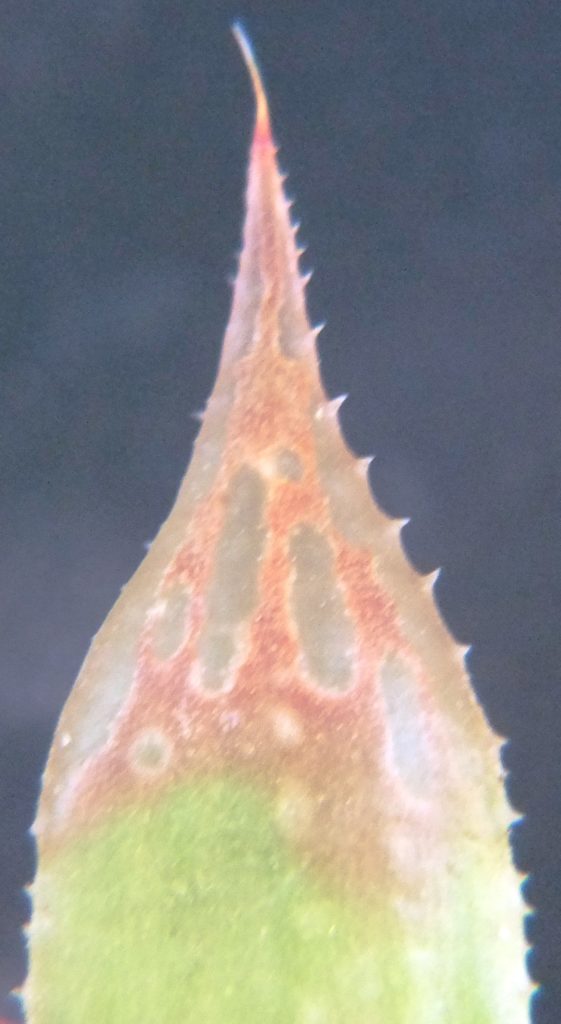

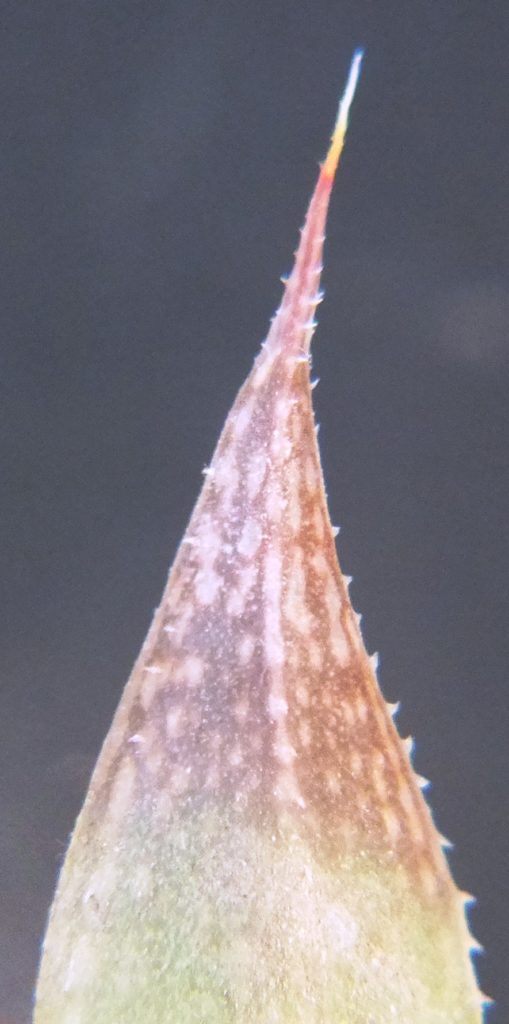

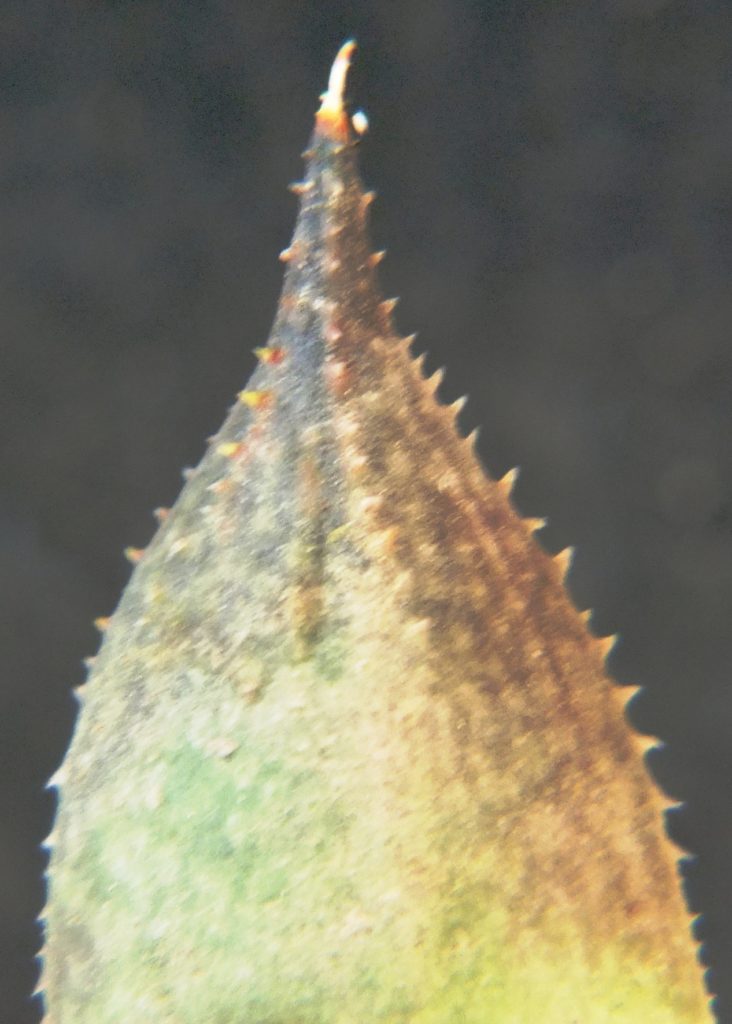

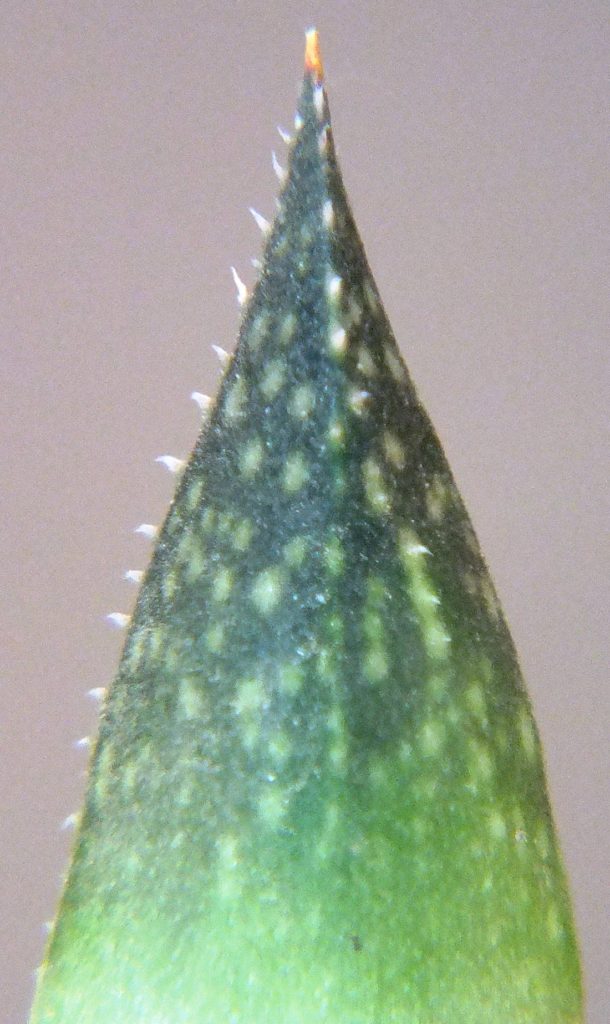

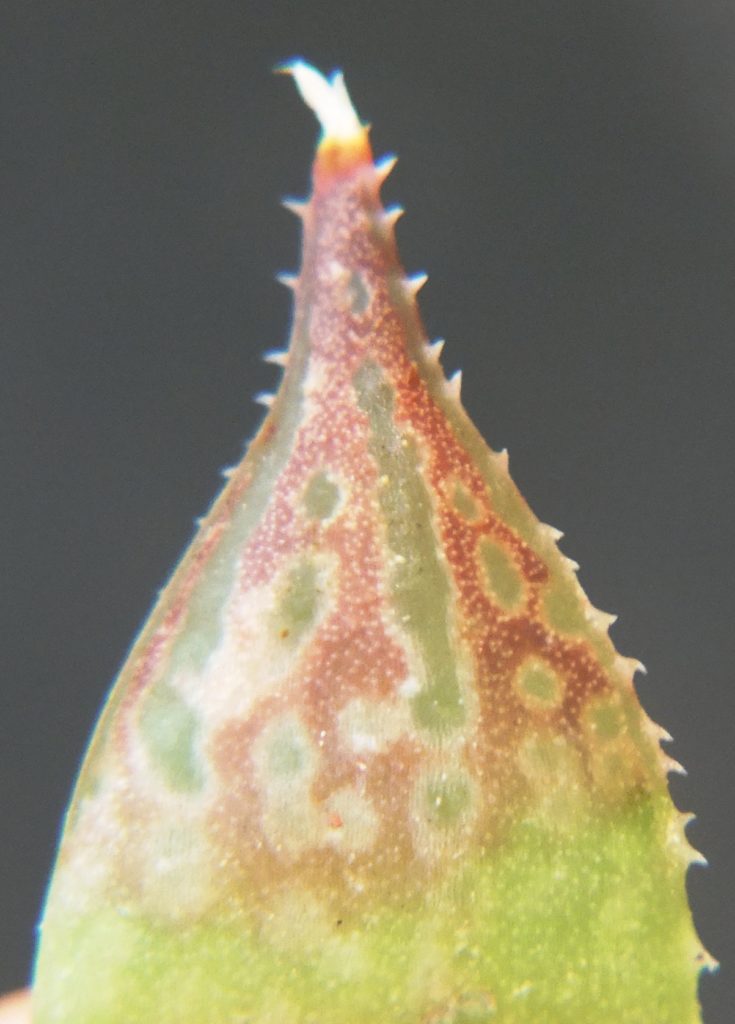

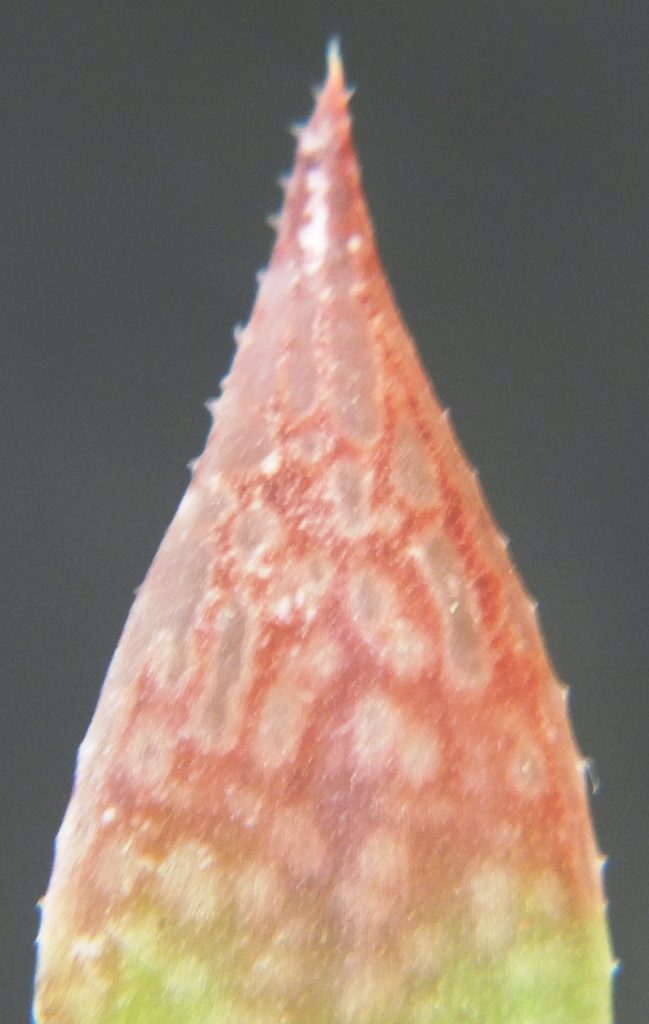

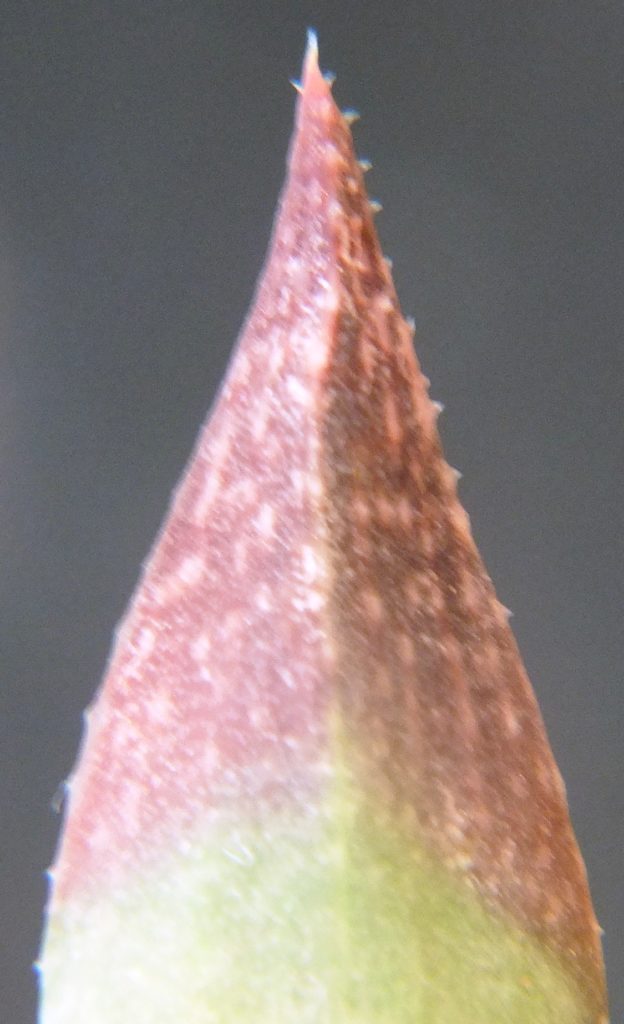

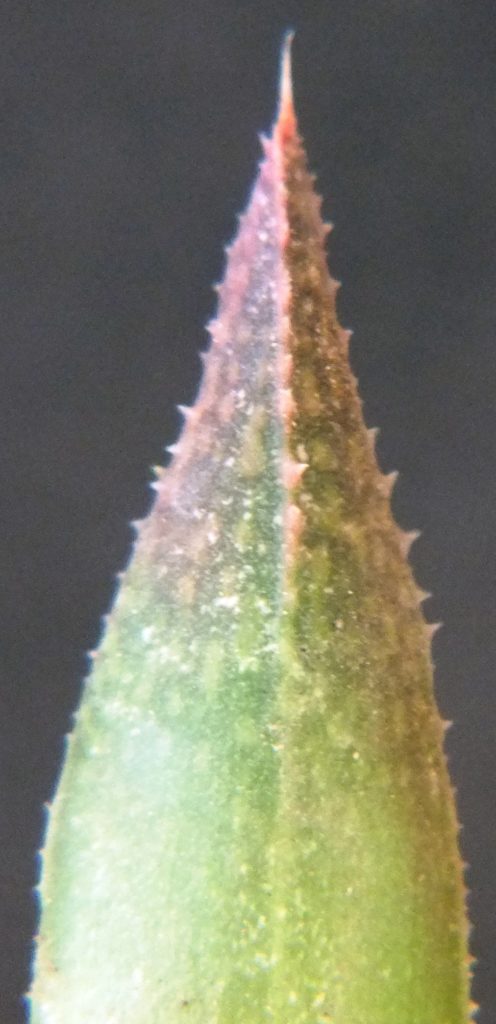

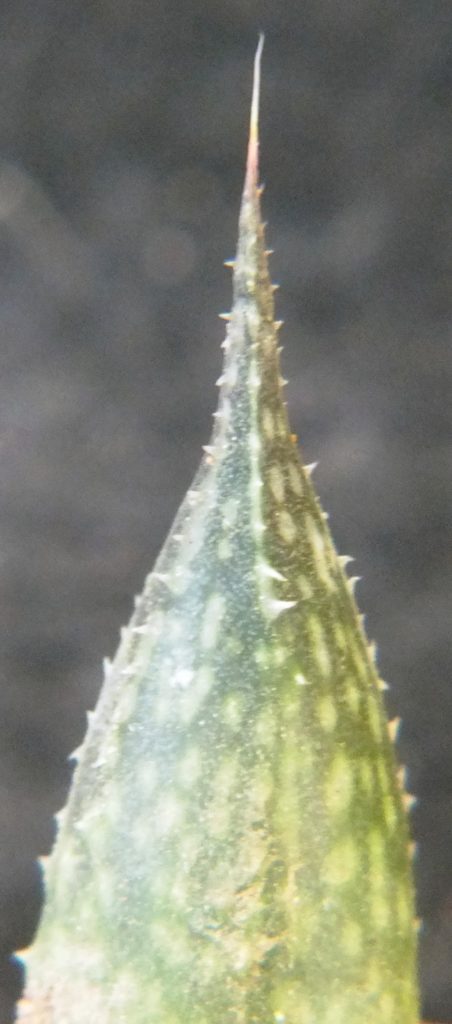

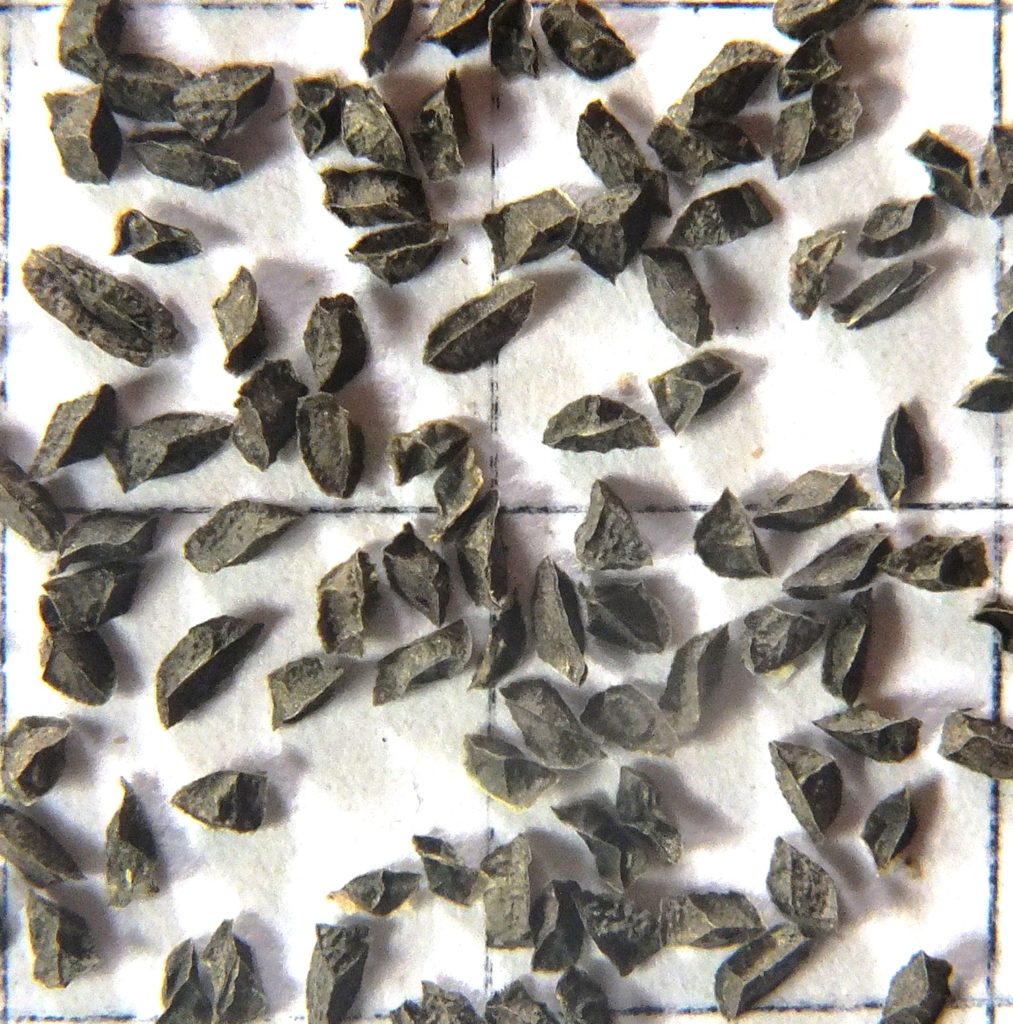

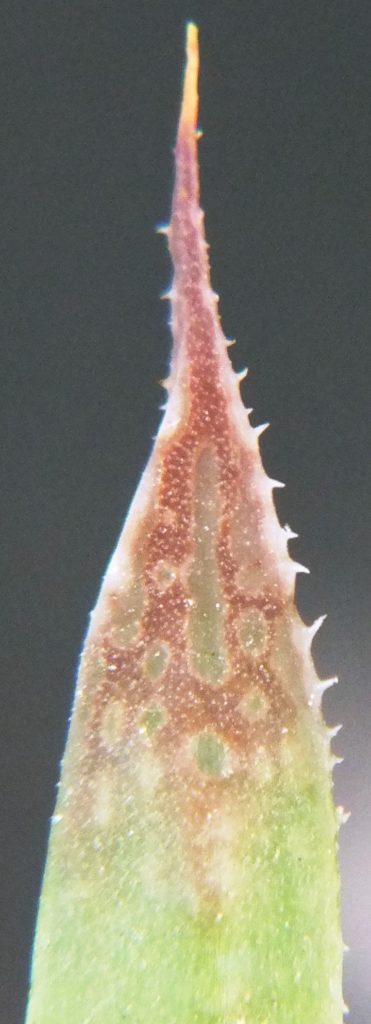

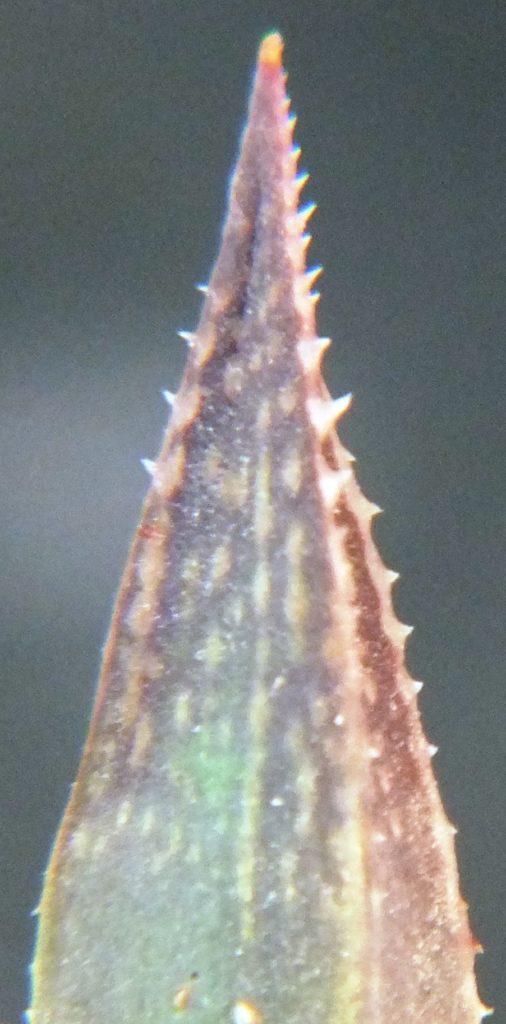

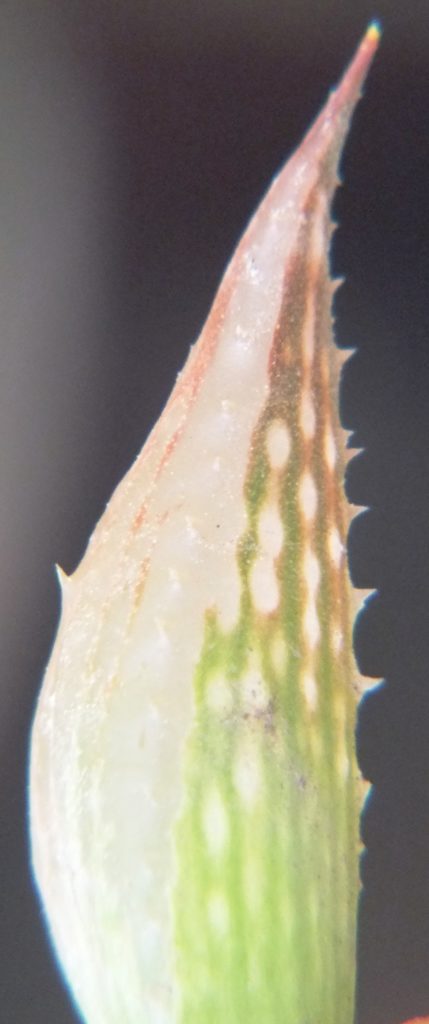

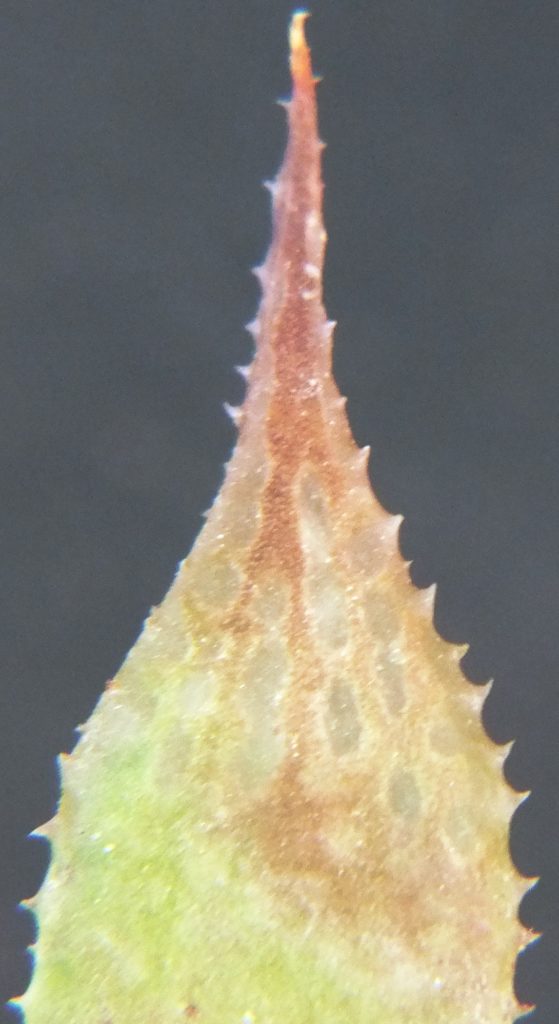

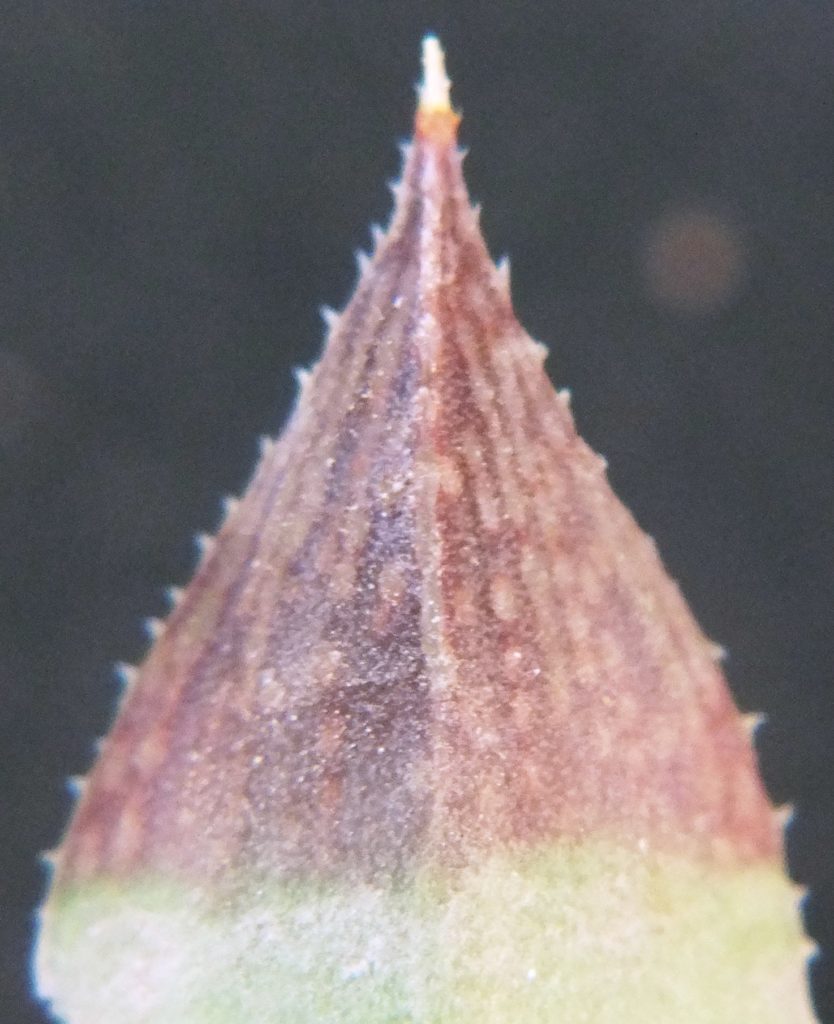

Haworthia maculata leaf tips, faces and backs

Die Nekkies – a selection of Haworthia maculata plants with their leaf faces and backs showing variability over this extensive area.

I took the following photographs originally just to show how much the leaves varied in the species. The only locality data record was Die Nekkies with no differentiation into populations. The variability was firmly established and became apparent even within populations where the degree of variation surprised even me. It was also extrapolated across the genus.

As an afterthought, this turned my mind to Farden and Smith’s observation about the idiocy of trying to make varieties in Haworthia attenuata on the basis of leaf characters where the individual leaves varied so much that several varieties could be detected from the same plant. This is exactly what Breuer, Marx and Hayashi are actually doing when they get carried away by their justification for new species, drawing conclusions from single plants because of the inability of the mind to hold many images. This is exactly the way in which “H. magnifica” is maintained as a species when the imagery is based on the original single plant originally described. There can be no such thing as “H. magnifica” because the variation across the range of populations from Riversdale to Riviersonderend is so immense and complex.

The following photographs show a random selection of plants and their leaf faces and backs from Die Nekkies. These were taken some time ago when I did not record actual populations. They do record the variability of plants and leaves over this wide area which I classify as Haworthia maculata. For subsequently photographed plants I have recorded my population collection numbers which are indicated on the map found in Die Nekkies Haworthia – A further visit and updated information.

A further report on Haworthia mirabilis in the Greyton area.

Appendix 11 to Haworthia Update Vol. 8.

In appendix 6 I reported on H. mirabilis just east of Greyton and also at Schuitsberg further east and south. I undertook this excursion to fill out on a population at Uitkyk MBB7092 west of Genadendal illustrated with one image in Haworthia Revisited. En route we discovered still another population along a road from Caledon to the northwest (8055 Hammanskraal), briefly called at a site east of the bridge on that road crossing the Riviersonderend (MBB8056). We also visited the population MBB8040 east of Greyton and explored some of the hiking trail between Greyton and McGregor.

The population 7092, H. mirabilis, at Uitkyk, is indeed interesting. It is a steep riverside, south facing, vertical slope. There are many plants that may not receive any direct sunshine for most of the summer and of course none in winter. It is really curious because there are groups of plants that seem to be holding clumps of moss, lichen and a modicum of soil to the rock. There are orchids, oxalis, shade-loving Asparagus, and all the small bulbs one expects in these moist south facing habitats. The rock seems to be metamorphosed from fault-shearing heat and pressure on shale. Among the illustrations is a view looking east along the road with the roadside south-facing habitat on the left. The Riviersonderend River is immediately on the right. In the distance ahead is Leeukop, the type locality for H. mirabilis ‘rubrodentata’. That is a dry north-facing slope.

The 8055 Hammanskraal population is about 5km due south of Leeukop and is quite new to me. We were attracted in passing to a very promising looking northwest facing shale ridge and were not surprised to find plants there. However, it does consolidate the western limits of the species. A paradox is that here the plants seem to be only in little pockets of soil in the shale ridges. There are none in the more friable and developed soil between the exposed unweathered shale. The plants were in seed and there were still a few flowers indicative of a flowering time a good two months behind populations to the north and east. The plant 8055.17 could very easily be mistaken for similar clones in populations northwest of Napier (‘subtuberculata’).

8056 is a population that Kobus Venter drew my attention to. We only looked along the road and did not spend much time there. This is similar habitat to Leeukop where the var. rubrodentata originated. That original description and name is associated with a variant with relatively long narrow leaves with well developed and very red spination. Of course the colour is associated with the northern aspect. Red spination is quite common elsewhere in H. mirabilis and is evident on the 8055 plants too. I include a view of a nearby site as evidence of road building vandalism. For some reason or other the road builders seem to have thought it necessary to scrape and ravage a wide strip of countryside between where the road eventually was established and a wonderful riverside steep slope full of Aloe glauca. It is really curious that there are several aloe populations like this at the H. mirabilis sites, but the two species seem to be exclusive with the Haworthia on the lightly less weathered and more sparsely vegetated area.

We called at the population 8040 east of Greyton because I wanted to obtain a sample to see if the colour was maintained in cultivation. I include a picture 8040.9 to show the offset which has no tubercles, spots, or spines on the underside of the leaves so commonly associated with H. mirabilis. I said of the var consanguinea (southwest of McGregor) that plants could be mistaken for H. mirabilis ‘notabilis’ from Robertson. It is true of this clone too.

The last thing we did was explore the start of the 15km Boesmansrivier hiking trail from Greyton to McGregor. It is along a traverse through the Riviersonderend Mountains. The Grobos River originates deep in the mountain about 5km southwest of McGregor and runs in a deep gorge toward Greyton. From Greyton the hiking trail voids the deep river valley and ascends a high ridge running parallel to the south of the river. Then there is a second deep valley again south of that. So the path is along the top of a high ridge from where it eventually does drop to a waterfall on the river. We never got that far but I assume the trail then follows the river and then climbs out again at the north eastern end. There were no accessible and likely habitats along the first portion of the trail. We did explore very promising looking habitat south of the trail start, but found nothing. This is curious because it is only about 1km north of the ZigZag path where the plants are abundant. Of course we know that plants occur along the trail northeast of the waterfall and had hoped to chance on suitable accessible habitat on the way there. I have included some pictures of the scenery to show how steep and rugged the terrain is. It is almost certain that there are more populations in the area. Given the adaptation to the Uitkyk habitat contrasted with both Leeukop and Hammanskraal one cannot rule out any possibility of more populations in these mountains. I include a photograph looking southwestwards to show the territory with populations known on those distant ridges both in the extreme west and again extreme east. Plants have been reported in the higher areas. There are also low mountains to the west behind and west of Leeukop unexplored. Hammanskraal would be discernible in the picture in the distance to the far right.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Willie Smal for access to Hammanskraal. My son Warwick for transporting and accompanying us. Kobus Venter for alerting me to the plants east of Leeukop. ♦