The area concerned is the long and wide contact zone between the Limestone stretching from Bredasdorp to Potberg, and the Bokkeveld shale north of that. The soils and vegetation of the two areas are grossly different. The limestones are agriculturally almost useless, while the shales are prime wheat and pasturage producing soils although relatively low yielding. The vegetation of the shales is Renosterveld and there are very few patches left. Large areas resemble ecological deserts with nothing of the original surface intact. Here and there are shale banks and associated quartz outcrops and also some remnants of tertiary deposits that overlie the shale. Under this deposit layer the shale has decomposed to kaolin and in places there are gravel sheets of fine quartz on white clay. The skeletal nature of these remnants is the saving grace but it is unbelievable to what lengths farmers must have gone to make fields arable. Enormous amounts of stone that have been carted away and dumped to make cultivated lands. Sadly the stone is often dumped on exposed rock and prime Haworthia habitat. The remnants are still under threat and a mindset that has developed in the road construction and maintenance arena is that roads must be clean and scraped fence to fence. Similarly there are farmers who want every square inch under control and in subservience to their production needs. Dense vegetation is abhorred and burnt to control predation of sheep by jackal and lynx. Vegetation adjoining crops is treated with weedkiller to minimize crop contamination. Crops are also grown in conjunction with animal production. When crops are in, the animals are on fallow land and on whatever is left of natural vegetation. It is the harsh reality of conservation.

Haworthias exist on those remnants. I have often pondered that maybe they have not been so severely suffered by habitat destruction but now I am not so sure. There are many remnants where nothing is to be found, and others are species rich for no obvious reason. It is therefore difficult to assess.

This chapter explores the occurrences of two species at 11 localities in the Ouplaas vicinity east of Bredadsorp, and records some of their oddities.

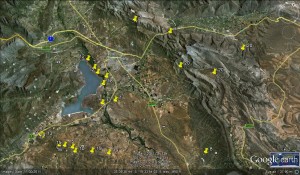

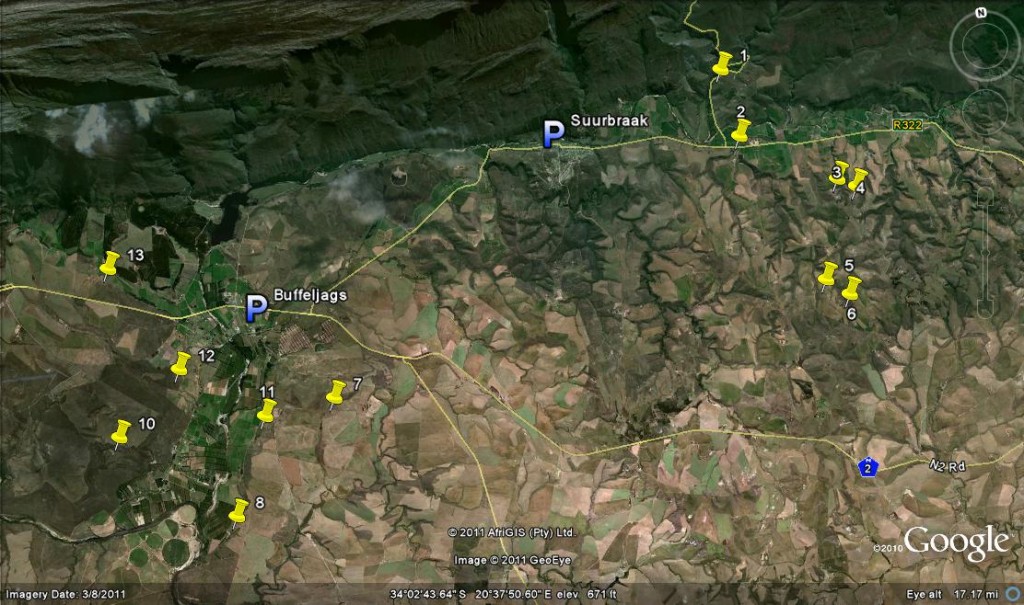

The area in question:

This is shown in the map Fig 1 and I need to re-capitulate what I observed on Die Kop because I do not think I have given proper account for the populations I saw and the variance that I encountered in my first exploration there. This is most unfortunate as the name H. hammeri has since been applied to one or more of the variants and without context. Changes have taken place there too, that now compound the issue. I have in Vol. 3 Pt. 1 given an account of H. mirabilis in the wider area and will not repeat all of it, restricting myself just to those few populations that impact directly in these new observations. What is considerably more relevant is the chapter 13 in Part 2 where the main role players are listed and now again emerging in stark reality..

I have changed the arrangement from that in previous accounts to deal with local groups. Thus three sets, H. mirabilis at Die Kop – 5 populations and re-visits, H. mirabilis at Spitzkop, Haarwegskloof and Langvlei – 5 populations, and H. mutica at Spitzkop,- 3 populations.

SET 1 – Haworthia mirabilis Die Kop

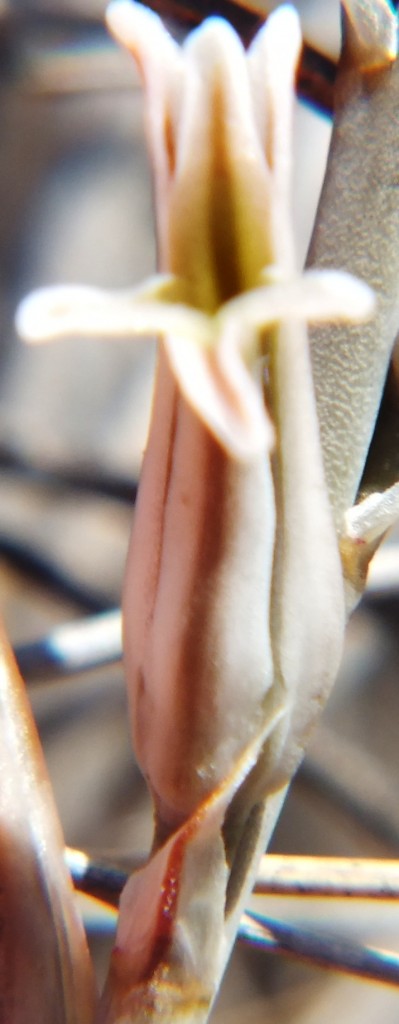

Subset 1 MBB7500 Die Kop E. Figs 2-8

Considering the wide array of populations and variants in the greater area, I concluded that these are most probably the result of interaction between H. mirabilis and H. mutica. The surfaces vary from shiny minutely tubercled to smooth, leaf tips rounded or pointed and flowering time is summer. This particular population is in a deposition area off the Silcrete inselberg.

Subset 2 MBB7502 Die Kop N. Figs 9-10

When I first explored here in 2006 I skirted north of the first hill on Die Kop (see fig.1 Map) and observed an array of plants that were more like H. mirabilis and I dismissed them as such. However Jakub Jelimicky and Gerhard Marx both indicated that their observations contradicted mine.

Subset 3 MBB7973 Die Kop N. Figs. 11-27

We went further north on this excursion passing through the area touched on in 2006 that was now dramatically different. The previous shrubbery was absent and the area was trampled and grassy with also Bobartia, a large grass-like Irid. It seemed unlikely that Haworthia previously there could have survived, but we had seen them before still further west and they may still be present. This new area we saw was densely populated with plants similar to but smaller than MBB7500.

Subset 4 MBB7503 Die Kop mid. Figs. 28-34

My memory of these plants, east of those above, was that they inclined more to H. mirabilis than plants from 7500. Fig. 18 is almost identical to a clone photographed at 7500.

Subset 5 MBB7974 Die Kop mid. Figs. 35-46

Change due to heavy rain and erosion was more apparent here. There was less influence of H. mirabilis and the resemblance to 7500 nearly complete although the plants were generally smaller. This may be because the substrate was more skeletal and eroded than at 7500. What was really curious was the plant pictured figs 45-6 with narrow slender leaves. We did not observe any other species there that could have generated this as a hybrid but we did not have opportunity to comb the entire area small as it is.

Subset 6 MBB7504 N Die Kop. Figs 47-55

This population is about 1km north on an isolated inselberg. The plants are small and more typically mirabiloid with rough surfaces and spined margins and keel. Fig. 55 shows a plant with characteristics of the 7500 plants, but otherwise I would say this population perhaps relates better to Tarentaal MBB6539 (see Updates Vol 3.1 note 17).

SET 2 – Haworthia mirabilis Haarwegskloof and Spitzkop.

Subset 7 JDV86-2 Haarwegskloof. Figs 56-63

This subset with subset 11, are included as a reminder of what other populations in the area are like. Originally when so much less was known, this was classified as H. heidelbergensis var. scabra and subsequently so many variants have been found that naming each is not deemed practical by me. It is probably 3-4km west of the following three populations and similar populations occur about the same distance further south at Kathoek and Beyersdal. There are other populations known to me that I have never sampled or photographed and the following task is to explore a large area between Bredasdorp and Spitzkop.

The plants at Haarwegskloof, at the time the pictures were taken in late spring, were both with translucence and without. The plants were small and with leaves erect.

Subset 8 MBB7964 Spitzkop West. Figs 64-81

Fig. 64 indicates how difficult it is to find these small plants until you know exactly what you have to look for. One starts the search walking and eventually end upon all fours! Fig. 65 also shows how cryptic the plants can be. The plants are some of the smallest I have ever seen. Fig.72 shows an unusual plant with rounded tips to the leaves and I will show this again in another subset. Why this is so significant is because if the H. floribunda similarity in so many of the populations in the general area. The photographs disappointment me in that my first reaction on seeing the plants, was the association with images of H. parksiana. The pictures do no seem to fully reflect this. Kobus Venter has related his experience of finding H. parksiana-like plants among seedlings of H. mirabilis ‘magnifica’.

The leaves are reflexed as in H. parksiana as they of course are in many populations of H. mirabilis ‘maraisii’. But it is a curious reminder of the floribunda-like leaves in so many populations and the problem of look-alikes.

The plants were on a south slope in an area with white quartz and we had identified this as the most likely place to find them out of the direct north or northwest aspect. But we then did find them there too.

Subset 9 MBB7965 Spitzkop West. Figs 82-86

The plants were again hard to find over quite an extensive area. Fig. 83 again shows the floribundoid leaf tips.

Subset 10 MBB7966 Spitzkop West. Figs 87-103

It is curious how these small localized quartzitic areas can be so different. This was about 500m further north. There was more kaolin present as well as fine gravel. At an intervening similar habitat we found only Acrodon demidiatus, absent from the previous habitats and also from this one where Gibbaeum austricola now appeared. Again all the plants were small with dark green leaves, virtually no translucence and surfaces ranging from mildly spiculed to only minutely tubercled or just rough. Figs 99-101 are of plants with distinctly floribundoid leaves.

Subset 11 MBB7935 Langvlei. Figs 104-108

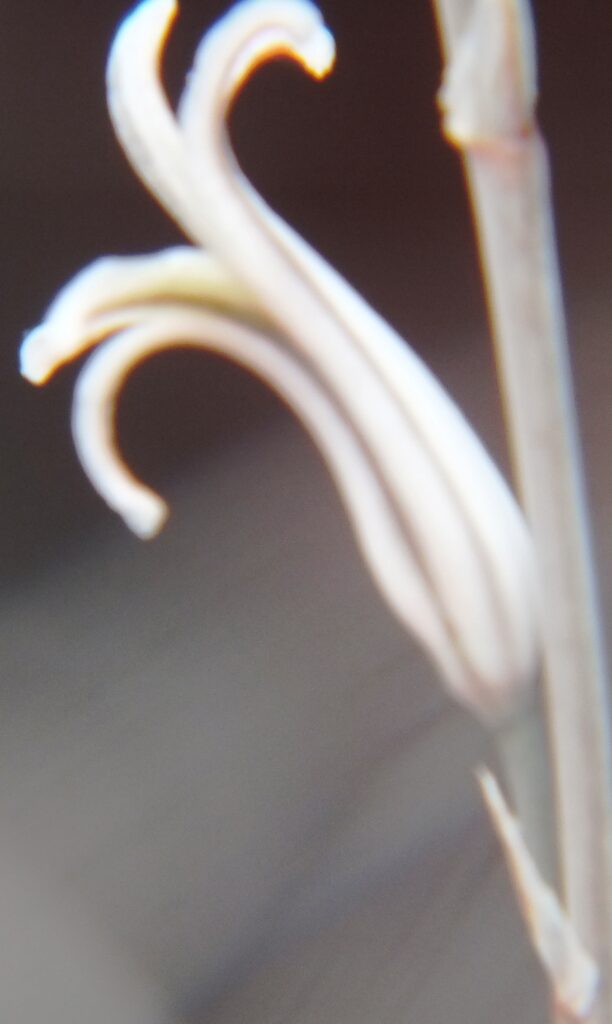

These are in white quartz and Aloe ferox is also present. There is moss present which is not the case at Spitzkop but true of Haarwegskloof. Curiously the pinched leaf ends as in fig. 106 have been observed in some plants of H. mutica too.

SET 3 – Haworthia mutica Spitzkop.

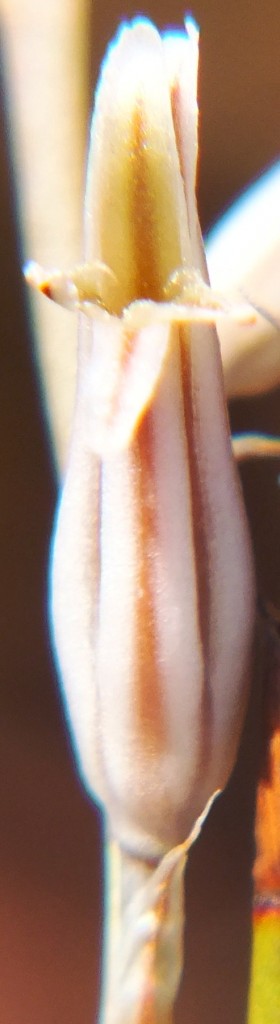

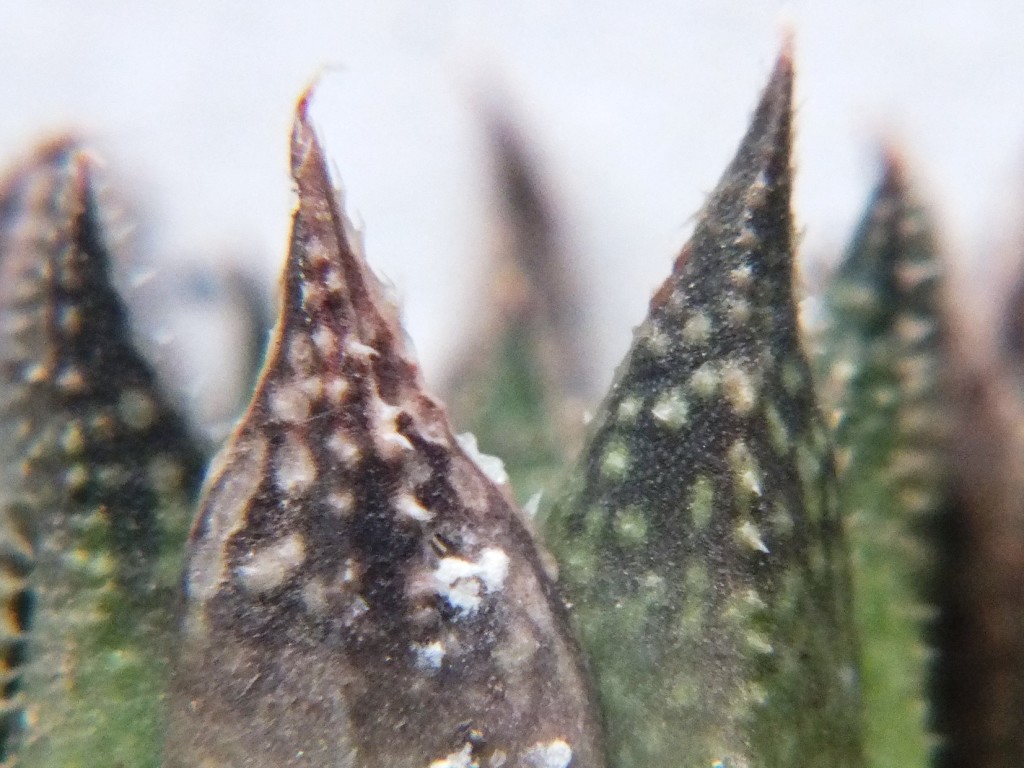

Subset 12 MBB7967 Spitzkop (quartz rock). Figs 109-148

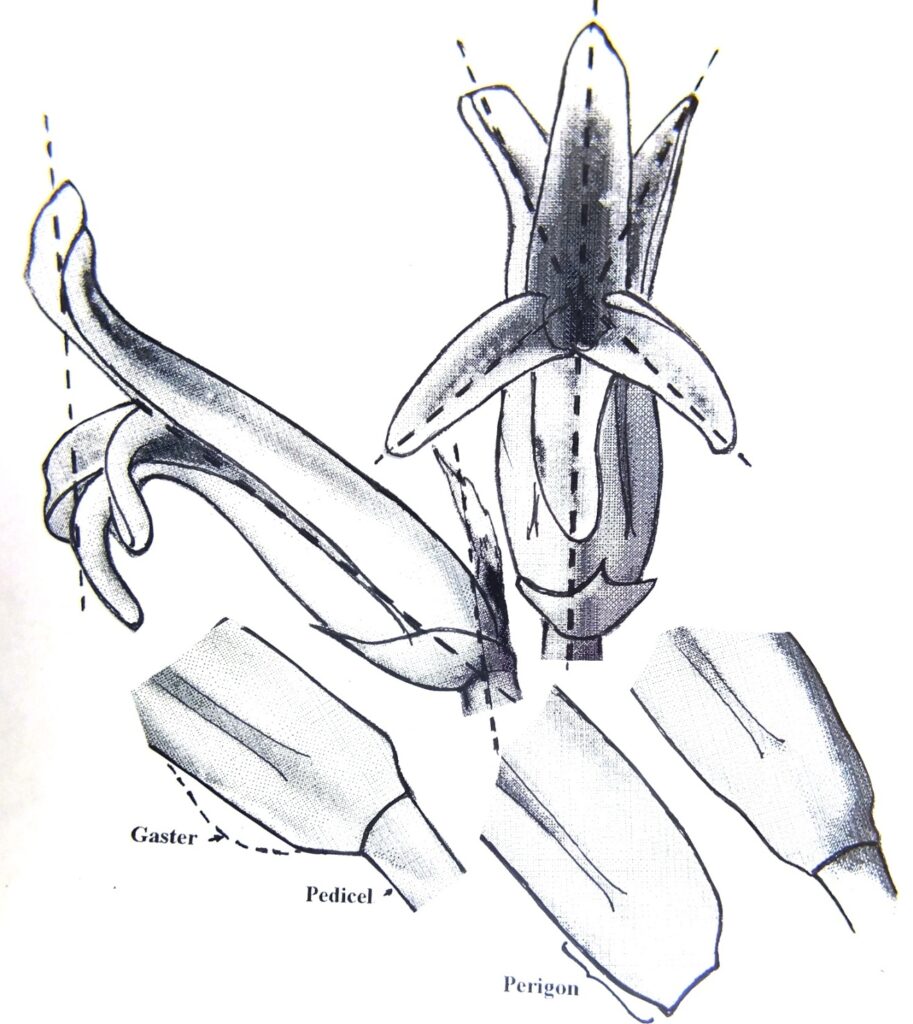

Although a small area of quartz in a cultivated field, the plants are densely concentrated in small areas. There were some dense clumps in the rocks and this is unusual for H. mutica. It is the variation in these plants that deserves close attention. Some plants have very rounded leaves, they can be quite elongate or short and squat, others have an end-awn, the leaves may be opaque or even translucent; the surfaces may be shiny and minutely tubercled or smooth. Colour may be reddish, golden, or green. Most striking is perhaps the venation. There may be anything from 3-13 straight lines or very anastomizing (veins joining). There is no sign of either true turbercles or surface spination and also none of marginal spines.

Subset 13 MBB7968 Spitzkop (pebbles). Figs 149-159

Curiously there is a shale ridge (fig.149) between this population and the first that one would think would be suitable habitat for this species as it is very like the Ouplaas habitat. But they were absent, perhaps because the ridge was lower down the slope. But a little higher where the shale was also exposed in smaller ridges the plants were also absent. Where they did occur was among small quartz pebbles to which the quartz may fragment. Fig. 157 shows a plant that was under the protection of small shrub and shaded.

Subset 14 MBB7969 Spitzkop East. Figs 160-161

This locality is about 3km east of the previous two at a slightly lower altitude. There is very little quartz but well exposed shale creating apparently suitable habitat as at Ouplaas now a short distance away. The area is well utilized by grazing animals and was very weedy, which may account for the fact that we found only two plants and these were not in the shale where we would have expected them.

Conclusion

I must here again relate the story in respect of KG35/70 of which there is only an herbarium specimen. That was found more than 40 years ago at Verfheuwel about 15km eastwards from Spitzkop. I was scrambling up a rough animal track to the top of the Verfheuwel hill when I saw some dried seed stalk less than 10cm high. The plants were tiny, greyish leaved with marginal teeth and rounded tips. I simply did not know what to do with them and identified them tentatively along with a few other populations from that wider area as H. maraisii. I went back to look for them several times with no luck. In 1996 I was with Kobus Venter and we found a strong population of larger plants not far away on the same hill. I recognize now that those first plants I saw were floribunda-like and that this similarity is commonly seen in populations of H. mirabilis in this area.

I speculated in Update 3 about the origins of H. mutica in the context of H. mirabilis and I do contend that these three H. mutica populations show characteristics that support this view. The Die Kop populations suggest to me a more recent amalgamation of H. mutica with H. mirabilis, to virtually reverse the process. The floribunda-like characters and even the parksiana resemblance also support this image of very close common origin and that particularly H. floribunda is simply a polytopic phenomenon in this south western area (polytopic – similar elements arising independently from the same common gene pool) and its genetic resources are embedded in H. mirabilis particularly. This seems to be definitely the case in the greater Swellendam and Heidelberg areas.

What is also so confounding is that now we have H. mutica occurring virtually undifferentiated in several different kinds of habitat. This is quite unlike the Van Reenens Crest area where similar habitat does not even have the same species. The H. mirabilis at Spitzkop west is unlike the other small plants in populations of H. mirabilis in the area and does seem to be differentiated according to habitat.

Acknowledgement:

Mr. Johannes and Pat Uys of Die Kop, Mr. Vlooi and Adele duToit of Die Kop, Mr. Gawie de Wet of Spitzkop (West), Mr. Franko de Wet of Spitzkop (East), Mr. Koos Badenhorst of Langvlei and Mr. Martin Mynhardt of Haarwegskloof. ♦