M B Bayer, Kuilsriver, RSA

Introduction

The object of this essay is to discuss where we are now with respect to classification of Haworthia. Despite my comments and observations stretching over 50 years, there are still taxonomists writing and arguing on the basis of method and practice that generated the anarchy of names that existed at the start of my involvement. This method is what is probably referred to as “typological” i.e. there is a single herbarium specimen and anything that departs from this in some mind catching way is a different and thus needs a new name. At the generic level, recent DNA studies show that Haworthia is indeed three separate entities (the subgenera), and that these cannot be rationally separated from the aloid genera. Formal classification requires that Haworthia thus be subsumed in Aloe (see Treutlein et al, Rhamdani et al and Daru et al). This is both incomprehensible and anathema to writers and collectors locked into method that does not rest on any insight to what the problem of species actually is, let alone take proper cognizance of the problems that exists at generic level.

In response to some of the expressed anxiety about the proposed changes to Aloe, Dr John Manning, in a personal communication, wrote…”Most folk follow the biological species concept, which in its simplest form proposes that species are groups of interbreeding populations that are more or less reproductively isolated from other species. The existence of infrequent hybrids does not invalidate it. HOWEVER this is just about always a purely theoretical construct because there is no experimental data in most species to back it up. In practice, therefore, folk use morphology as a surrogate for reproductive isolation on the argument that discontinuities in morphology will coincide with these reproductive boundaries. Naturally there are all sorts of natural variabilities within species and so it becomes tricky to decide which of them fall within the boundary of the species and which fall outside of it”.

Two interesting things arise from this. Firstly, a “species” is itself a biological entity and there are not (or should not) be species that are not biological. Secondly there is a difference between a species concept and a definition. The concept is a general idea, while a definition lays down requirements that must be met. It might be better to say…”species determined by their interbreeding potential”, than use the term “biological species”. There is a huge amount of real experience and observation of the interbreeding capabilities of Haworthia both in the field and in cultivation. This suggests that if we really followed this criterion for determining in the genus then most of the Latin species names are superfluous, as I indeed consider them to be. Therefore, while there is a problem with the formal recognition of genera, the seems to be a total vacuum in respect of considerations around the constitution of species and how they can be, or are to, be circumscribed.

I have of course based what I regard as Haworthia species on a view of species as dynamic systems in a geographic framework, because history and my own long experience suggest that there are no morphological (or biological) criteria that produce the kind of classification that writers have produced or that collectors may need or expect. I proved by my studies in Oxalis, that morphological criteria can be extremely misleading, and that characters (or even character sets) thought to be useful in delimiting species, may in fact vary more within species than between species. I observe that this is true in many other genera. Flowers have recently been touted again by aspiring taxonomists as characters that will solve problems and it has even been said that I have ignored them. This is not true. I do not deny their value as characters. My experience simply suggests that variation and similarities in floral characters, mirror the situation with regard to vegetative morphology and may actually provide evidence for further amalgamation of species and reduction of names. This essay thus explores the situation in a data set, fortuitously available by virtue of modern digital photography and opportunity.

The elemental issue underlying all of this is dependent on the species definition. If some floral character is, or characters are, identified and specified as species characters then of course they would acquire significance in that context. What I can only show is that I observe nothing of the kind to relate to such a definition and insist on as species as systems in a geographic framework. Can they be rationally organized in any other system?

The hypothesis this essay addresses is that the floral morphology can be used to identify and circumscribe taxonomic ranks in Haworthia.

Overview

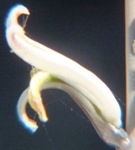

Originally I very laboriously drew flowers – often only one per collection. But one of my projects was trying to find more consequential objective evidence than just subjective vegetative differences to distinguish between H. reticulata and H. herbacea. I used a range of floral measurements but found the variation so great that to get a statistically significant result would have entailed many more samples than the number I used. Doing this would have been both very labour intensive and very destructive to the populations. I must point out that I am confident I could separate H. arachnoidea, H. mirabilis, H. pubescens as well as H. herbacea and H. reticulata (to some degree), all in the Worcester area, on the basis of their flowers. But this is not the level at which any other solution is needed beyond the appearance of the plants. There are only general differences by which one can separate H. herbacea and H. reticulata in respect of both vegetative and floral characters. H. wittebergensis could probably be identified just on the basis of its small white and more recurved flower, but its vegetatitve characters are quite adequate for the purpose.

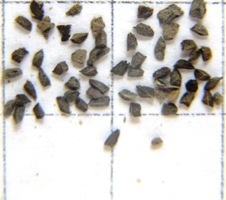

Photography in those early days was not an option for recording flower detail. The advent of digital photography changes that quite dramatically and this essay is an exercise using this technology to attempt to document field observations. I photographed flowers as available in approximately 30 populations during February 2012, and these are used now in a posteriori manner to test the hypothesis regarding flowers. These images cover three species as I recognize them as systems in a geographic context viz. H. mirabilis (20 populations from three geographic zones), a summer flowering set of H. mutica (3 populations), H. floribunda (5 populations). Several outlier populations are added although sometime by single clones (see Table 1 listing the accessions. Map 1 (at end) indicates relative geographic position). These photographs provide a pictorial record of variation and difference within populations, between populations of the same species and between populations of different species.

Data

1. The plants. Figure Set 1 is a set of to 4 each, of the plants as they are in the populations covered. I have done this as a reference to how the names were derived and as I use them. The plants are far more variable than is generally understood and four images per population is really grossly inadequate as a sample to base a circumscription on. In the case of 7163 H. mirabilis, Frehse Reserve, S Riversdale, I have included pictures of plants (no flowers) because this is the type locality for the name H. magnifica (=H. mirabilis) that is widely used without any consideration of the range of variants there and how they may relate to other populations of H. mirabilis that are equally variable. Curiously there were no flowers and it appeared that the few plants that had flowered had done so earlier than expected. The same applies to a very similar population 6651 from a little to the southwest where there was only a single open flower. But two other populations viz. 7778 and 7818 in the area had many flowers at the time. It was rather similar at Van Reenens Crest where the various populations had not flowered with equal vigour and at some it was not possible to get a respectable number of flowers. It should be noted that in a good season with some summer rain, the plants will flower more successful with more plants flowering and some plants producing successive inflorescences. Thus the flower season could be extended be several weeks. Note that in the case of 7976 H. floribunda I did not take plant pictures for this second population.

Table 1. List of populations and identifications.

1. Haworthia mirabilis – eastern zone, Riversdale area (cf H. magnifica).

6651 H. mirabilis, E Riversdale.

7163 H. mirabilis, S Riversdale.

7778 H. mirabilis, Komserante, E Riversdale.

7818 H. mirabilis, Windsor, SE Riversdale.

7809 H. mirabilis, Koeisekop, Heidelberg.

2. H. mirabilis – central zone, Swellendam area.

7887 H. mirabilis, Rotterdam.

7912 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil.

7913 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil.

7916 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest.

7917 H. mirabilis, NE Dam VR Crest.

7918 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest, SE Dam.

7919 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest, Game camp.

7955 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest.

7959 H. mirabilis, W Van Reenens Crest.

7960 H. mirabilis, Kruiskloof.

3. H. mirabilis – western zone, Greyton area (cf. vars beukmannii, rubrodentata).

7262 H. mirabilis, S Greyton.

7978 H. mirabilis, Schuitsberg.

7979 H. mirabilis, Nethercourt.

7980 H. mirabilis, E Ouplaas.

7981 H. mirabilis, Schuitsberg N.

4. H. mutica – north-eastern zone, Buffeljags (Swellendam area, cf. H. groenewaldii).

7801 H. mutica, Buffeljags.

7888 H. mutica, Rotterdam 1.

7889 H. mutica, Rotterdam 2.

5. H. floribunda – central zone, Swellendam area.

7774 H. floribunda, S Swellendam.

7910 H. floribunda, Rietkuil.

7963 H. floribunda, Niekerkshek.

7975 H. floribunda, Rotterdam 1.

7976 H. floribunda, Rotterdam.

6. H. mirabilis – outliers and ‘outgroups’.

7248 H. mirabilis, Ballyfar, Infanta.

7513 H. mirabilis, Klipfontein N Bromberg.

7612 H. mirabilis, Diamant W.

7780 H. retusa ‘geraldii’, Komserante.

7781 H. retusa ‘foucheii’, Komserante.

7920 H. retusa ‘ nigra’, Van Reenens Crest.

7974 H. mirabilis, Klipfontein, Potberg.

7982 H. mirabilis, Melkhoutkraal, Goukou.

JDV87-132 H. parksiana, Mossel Bay.

The plant images :-

SET 1. H. mirabilis, Eastern Zone.

6651 H. mirabilis, SW Riversdale

6651 H. mirabilis, SW Riversdale

7163 H. mirabilis, Frehse Reserve, S Riversdale

7163 H. mirabilis, Frehse Reserve, S Riversdale

7778 H. mirabilis, Komserante

7778 H. mirabilis, Komserante

7818 H. mirabilis, Windsor

7818 H. mirabilis, Windsor

7809 H. mirabilis, Koeisekop

7809 H. mirabilis, Koeisekop

SET 2. H. mirabilis, Central Zone.

7887 H. mirabilis, Rotterdam

7887 H. mirabilis, Rotterdam

7912 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil

7912 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil

7913 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil

7913 H. mirabilis, Rietkuil

7916 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7916 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7917 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7917 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7918 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7918 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7919 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7919 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7955 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7955 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7959 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7959 H. mirabilis, Van Reenens Crest

7960 H. mirabilis, Kruiskloof

7960 H. mirabilis, Kruiskloof

SET 3. H. mirabilis, Western Zone.

7262 H. mirabilis, S Greyton

7262 H. mirabilis, S Greyton

7978 H. mirabilis, Schuitsberg

7978 H. mirabilis, Schuitsberg

7979 H. mirabilis, Nethercourt

7979 H. mirabilis, Nethercourt

7980 H. mirabilis, E Ouplaas

7980 H. mirabilis, E Ouplaas

7981 H. mirabilis, Schuitsberg N

SET 4. H. mutica in its NE zone, Swellendam.

7801 H. mutica, Buffeljags

7801 H. mutica, Buffeljags

7888 H. mutica, Rotterdam 1

7888 H. mutica, Rotterdam 1

7889 H. mutica, Rotterdam 2

7889 H. mutica, Rotterdam 2

Set 5. H. floribunda in its western zone, Swellendam.

7774 H. floribunda, S Swellendam

7774 H. floribunda, S Swellendam

7910 H. floribunda, Rietkuil

7910 H. floribunda, Rietkuil

7963 H. floribunda, Niekerkshek

7963 H. floribunda, Niekerkshek

7975 H. floribunda, Rotterdam 1

7975 H. floribunda, Rotterdam 1

7976 H. floribunda, Rotterdam – not illustrated.

SET 6. Outliers H. mirabilis and some relevant populations.

7248 H. mirabilis, Ballyfar

7248 H. mirabilis, Ballyfar

7513 H. mirabilis, Klipfontein, N Bromberg

7513 H. mirabilis, Klipfontein, N Bromberg

7612 H. mirabilis, Diamant

7612 H. mirabilis, Diamant

7720 H. retusa ‘nigra’. Van Reenens Crest

7720 H. retusa ‘nigra’. Van Reenens Crest

7982 H. mirabilis, Goukou

JDV87132 H. parksiana, Mossel Bay

Haworthia flowers – some comments as a character source, part 1

Haworthia flowers – some comments as a character source, part 2

Haworthia flowers – some comments as a character source, part 3

♦