I have several times been rather taken aback when botanists have been among those who have derided the fact that I have not apparently looked to flowers as a source of characters for identification of Haworthia species. Others have intimated that there are diagnostic characters in the seeds and even in the capsule structure. The essence of this kind of complaint is that there are these definable units called ‘species’ and that there is some linear and dichotomous set of characters by which they can be separated. The perception remains alive for the technology of surface structure, pollen sculpturing, DNA and molecular structure, and expectations which flow from and for these real and presumed character sources.

My opinion is that these techniques or methodologies will not tell us much more for Haworthia than what can be deduced by common-sense scrutiny of the plants. They may be extremely exciting and enlightening in view of broader relationships and theories of origin and migration even of vegetation. But their value to the collector and grower will always be minimal.

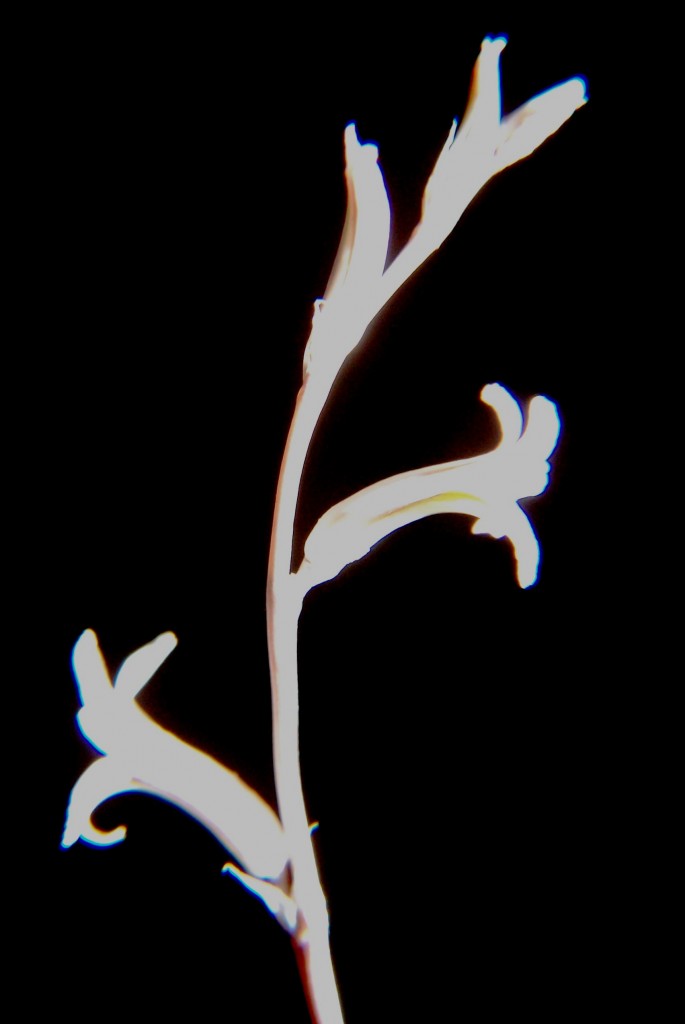

Here I want to picture some flowers of the subgenus Haworthia and show that while there is indeed ‘character’, the magnitude and ranges are such that they cannot be of any assistance for separating those elements that can be practically recognised as ‘species’. It is more probable that it will rather fuel the argument for less species. In the subgenus Hexangulares, my observation has been that while the species are vegetatively readily distinguishable and in most cases, geographically quite discrete, the flowers are indistinguishable. Within‑species differences may exceed the differences between the flowers of different species. In the case of subgenus Haworthia, it can be observed that in the one case where the flower is really notably different i.e. H. nortieri var. globosiflora (including H. pehlemanniae) there is a gradation to the normal flower of H. nortieri var. nortieri. Thus, within species difference may exceed that between species.

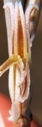

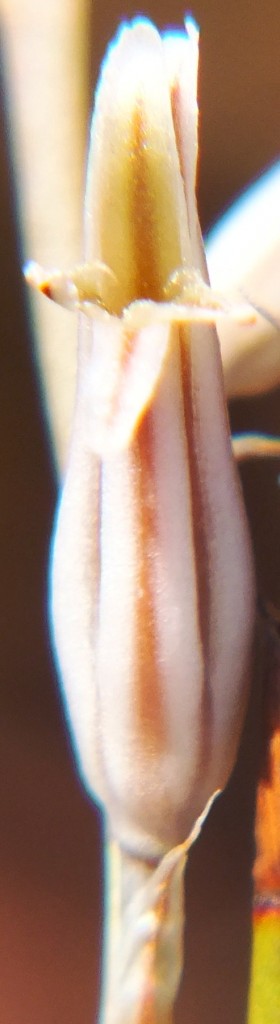

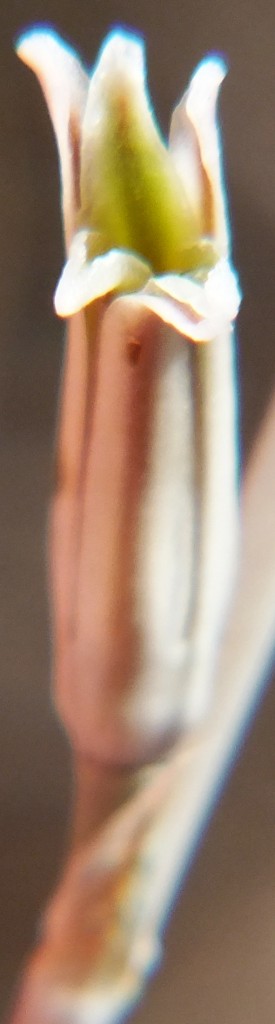

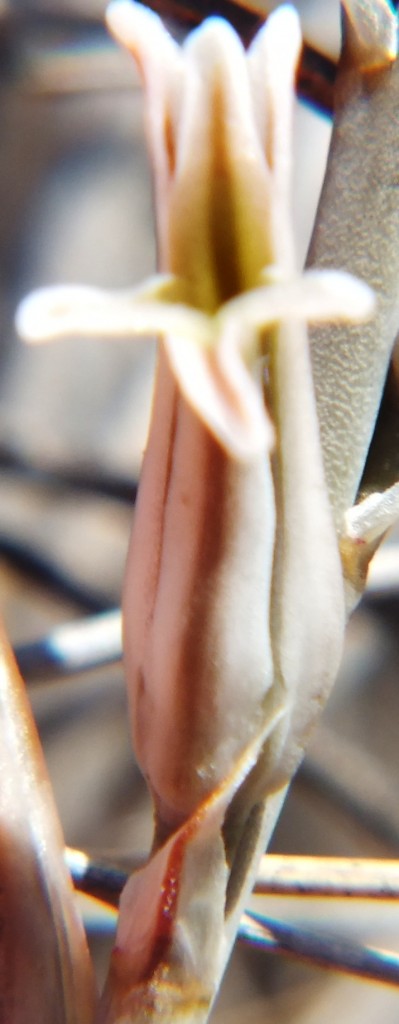

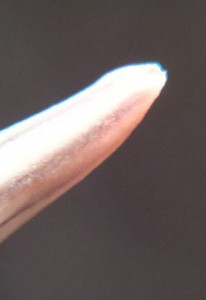

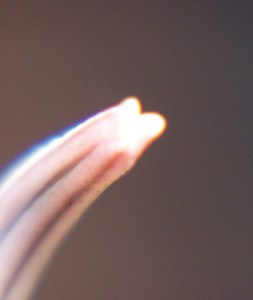

The flowers of H. herbacea and H. reticulata are interesting because they are quite large and the tip of the flower bud is ‘fish-tailed’. The tips of the upper outer petals are pinched together. But this character is present in the whole of the southern Cape complex of about nine species and extends to Little Karoo species as well.

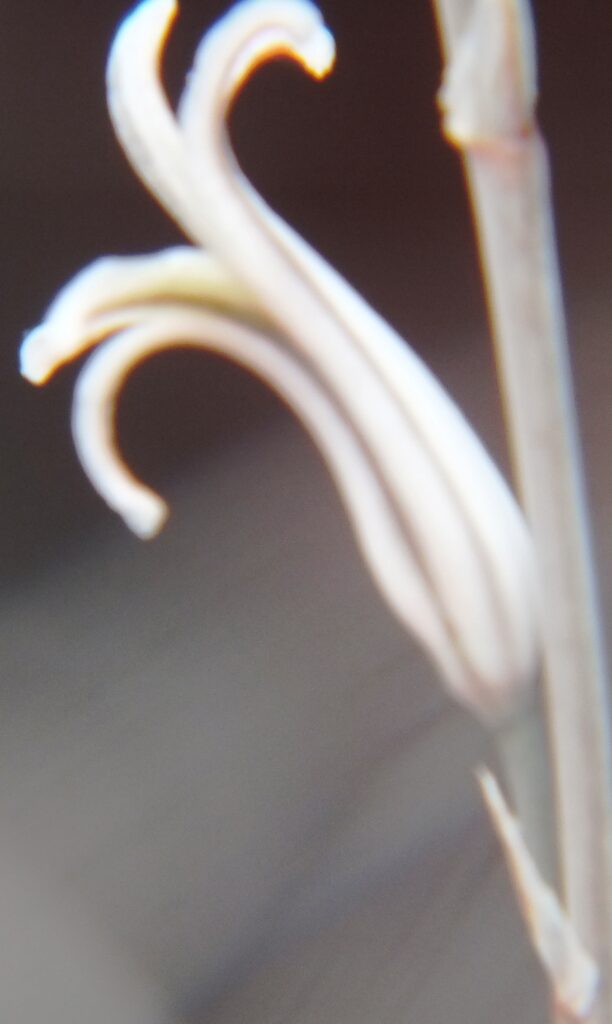

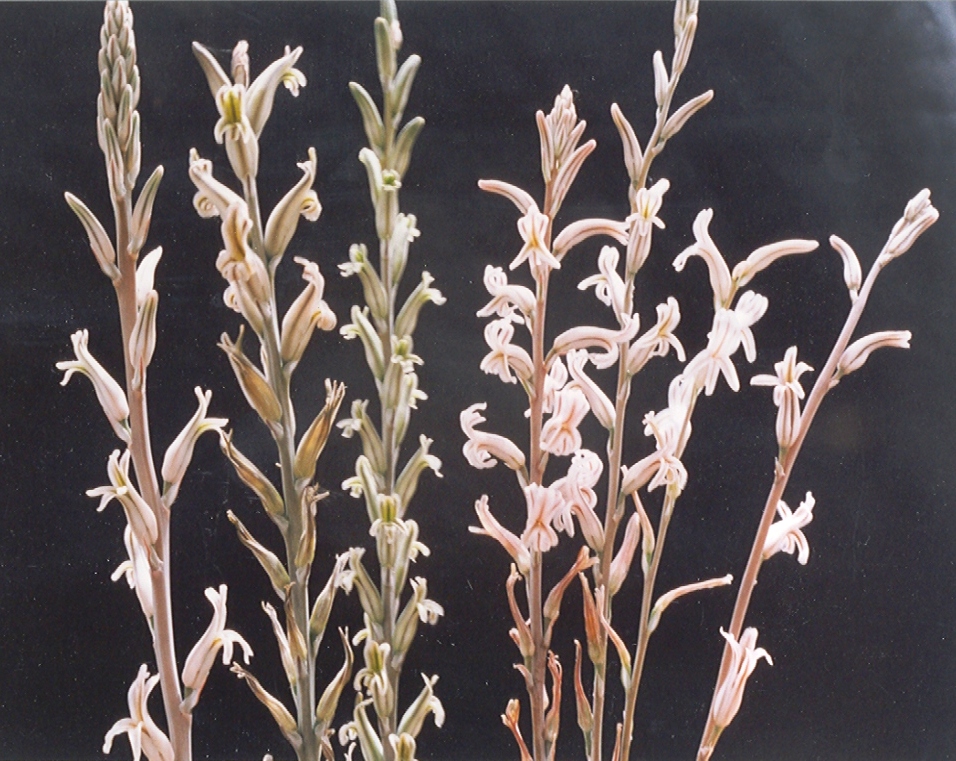

Here are H. maculata and H. nortieri var. nortieri – the former from the Audensburg north of Worcester, and the latter from the Sneeuberg in the Koue Bokkeveld north of Ceres. The plants are generally very similar and the argument to maintain species identity is no more substantial or tenuous than for any others of the subgenus. The flowers generally are different. H. maculata has the fish-tailed bud of H. herbacea and H. reticulata. This is evident in the illustration. The impact on the open petals is quite marked in that the upper outer petals tend to have pinched ends and the flower appears a little more regular i.e. the petals are equally spaced on radii from a point centred on the mouth of the tube. Colour is notable in this case because most of the Audensberg H. maculata flowers are notable pinkish. In the H. nortieri illustrated here they are white (ignoring the usual darker colour of the mid-vein). But I have photographed the one plant of H. maculata in which the colour is also white and the flowers less regular. It is almost impossible to separate this flower from that of the H. nortieri illustrated. This observation is also restricted to these particular specimens. It is well known that H. nortieri flowers can be very colourful with a notable yellow tube (yellowish-green, golden yellow and canary yellow fide G.G. Smith 1950).

The pinched bud does not always produce a more regular flower, and in H. maraisii, H. magnifica and H. mirabilis quite the opposite may occur with the upper outer petals almost overlapping behind the inner upper petal.

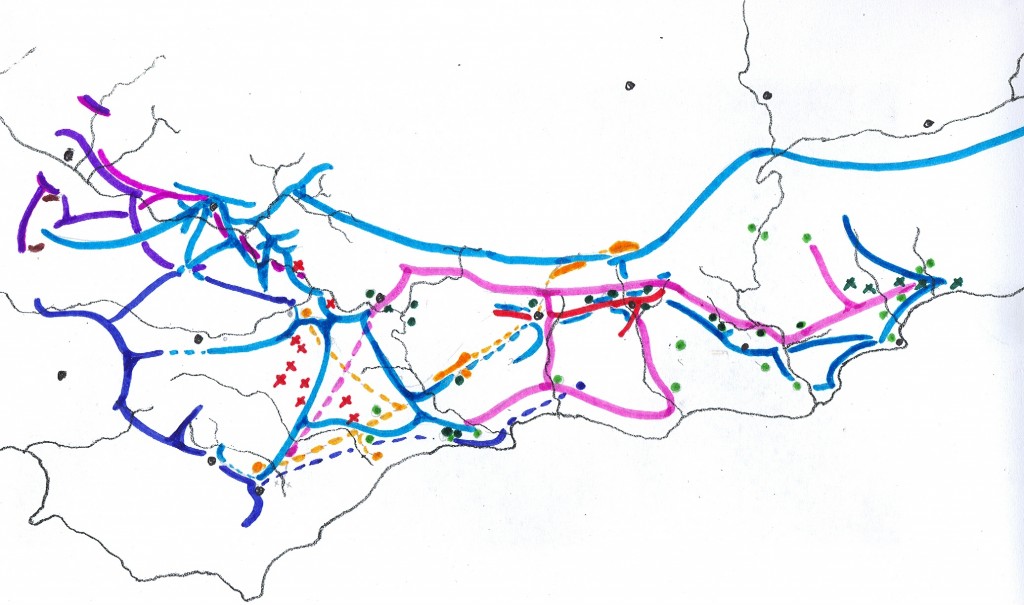

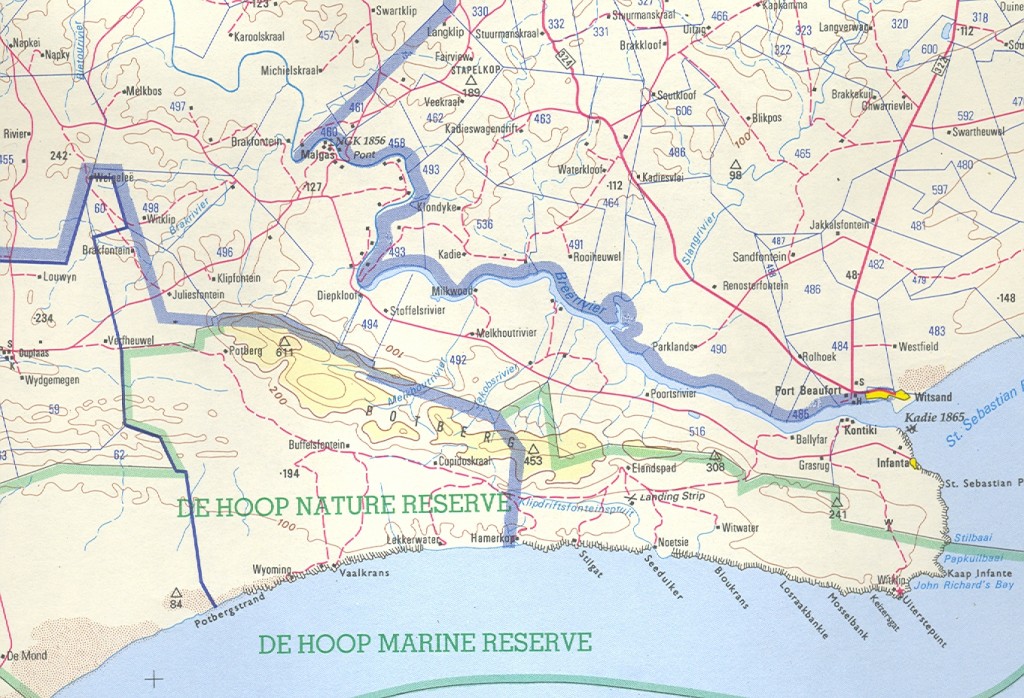

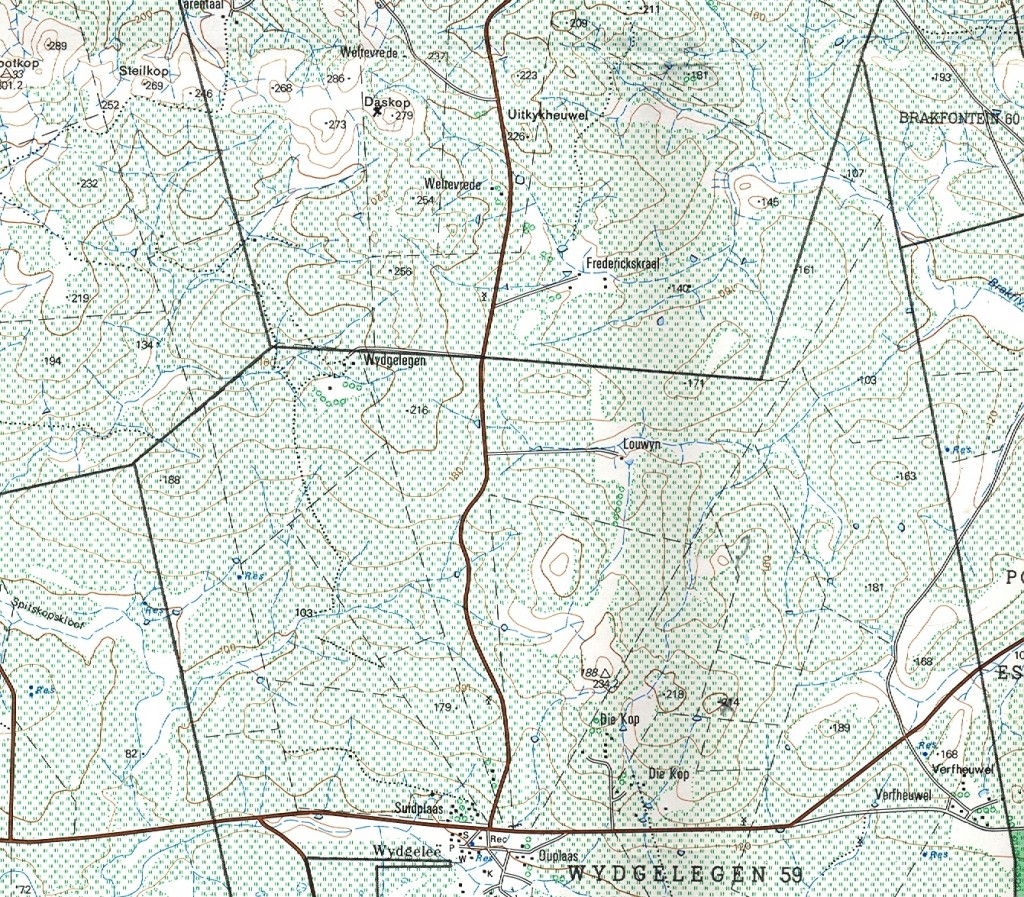

It has become increasingly evident to me that the separation of H. arachnoidea and H. mucronata as two independent systems, and therefore species, is difficult. Therefore I illustrate five specimens from four populations in:

The spike on the left is of a doubtful population of H. arachnoidea. The plants are spinose as H. arachnoidea is supposed to be, but generally less than is expected in that species, and its location between Barrydale and Montagu makes it suspect. The second spike is that of unmistakeable H. arachnoidea var. setata from Prinspoort where the variety nigricans and H. mucronata var. inconfluens are also in proximity. The third spike is that of H. arachnoidea var. arachnoidea from west of Robertson. The fourth and fifth are of a collection from near De Doorns in the Hex River Valley. There are four plants in the collection and they have translucent spots on the leaf rather similar to H. marumiana var. dimorpha. The inflorescences are quite lax and as these two shown occupy a place in the greenhouse alongside the Robertson H. arachnoidea, it is obvious that the sparse lax spike is not light influenced. The flowers are sparsely spaced on this lax spike and the tube and flower colour is notable greenish. There does not seem to be any notable consistency in these differences and in many collections this kind of difference appears. The plants and flowers obfuscate the separation of H. arachnoidea and H. marumiana. The problem also arises as to how to name it. It is not typically H. arachnoidea var. arachnoidea as the nomenclatural system requires, and neither is it any of the other named variants.

The two left spikes are of an H. arachnoidea/H. mucronata intermediate from near Montagu. The flowers are more compressed together on one spike than on the other. The collection is notable for the intense yellow colour in the tube. The third spike is from the same geographic continuum also near Montagu but slightly eastward, inclining more to H. mucronata; as do the collections and next two spikes from Schoemanspoort near Oudtshoorn and the Touwsberg north-east of Montagu. The collections are probably of the variety H. mucronata var. mucronata. But I have explained elsewhere that H. arachnoidea var. nigricans is a buffer to absorb these problem elements which are neither one species nor the other, and not constituting any geographically cohesive entity. Incidental is that the third spike’s origin is in JDV97/56, a collection which also has the number MBB6689 and which contains individuals which could be H. arachnoidea var. nigricans, H. mucronata var. mucronata, H. mucronata var. rycroftiana, or none of these! This helps explain why I object so to opinions which are based on the unrecognised contention that one specimen can represent a population, a variety or a species. It also shows that it is better to work with a single accession system and one collector’s number rather than generate a series of personal numbers.

Is a montage of two spikes on the left of H. arachnoidea var. nigricans from between Barrydale and Montagu. Then there is a spike from a plant from Waterford near Jansenville (my new H. decipiens var. virella). The plants are on the broad interface of that variety with H. decipiens var. xiphiophylla and they are not typical of anything. The next two spikes are from plants of H. arachnoidea var. scabrispina from south-west of Laingsburg. The differences are self-evident viz. a densely compacted raceme and a sparsely flowered one. Colour also differs. The sixth and seventh spikes are of H. decipiens var. pringlei from Mt Stewart and of H. cooperi var. gordoniana from north of Jeffrey’s Bay (this latter is actually close to H. cooperi var. picturata). The differences across the figure are actually minuscule and when one has to compare several spikes from each collection these differences become quite untrackable.

Consists of a specimen which on vegetative grounds is unquestionably H. cymbiformis (but which variety is it? a la H. arachnoidea above). In the context of its near neighbours on the Zuurberg, and their similarities, it is actually continuous with H. cooperi. The plant (and others in the population) is very bright green yet in every other vegetative aspect is typically cymbiformis. The inflorescence is a bit sparse while the flowers are less white and perhaps sturdier than any norm which can be stated for that species. However, this inflorescence and flowers do not enable any better differentiation of the series of populations which link H. cooperi, several of its varieties, and also H. aristata in that area. The second and third spikes are from a collection of H. decipiens var. decipiens from south of Aberdeen. They are very different from each other. The fourth spike is of H. cymbiformis var. incurvula from Pluto’s Vale (and I have found it possible to make a perfect match of such a flower with the very improbable H. pulchella var. globifera, which is patently from another system). The fifth spike is from H. cooperi var. viridis and the last two are of H. cooperi var. isabellae from Holriver, south of Patensie and Milton south-west of Hankey.

Lastly Figure 6. These are flowers of H. bolusii var. blackbeardiana from Cradock, H. decipiens var. decipiens from east of Willowmore (note the many florets per bract), and H. decipiens var. decipiens from Springbokvlakte. The fourth spike is of H. cooperi var. gordoniana where it intergrades to H. decipiens at Willowmore and Uniondale. The last is another also of H. decipiens var. decipiens from the Springbokvlakte.

If any one species complex (as I have identified and recognised them) is taken, the same problem of variation arises. The variation in the flowers is of the same degree and intensity perceivable in the size, leaf arrangement, number, colour, texture, spination and armature of the rosette and leaves.

The conclusion I would like to make is that it is not possible to generate a classification system on any other logic than that I have used viz. geographic arrangement and broad vegetative similarity. It is possible to generate a diagrammatic model to show a cladistic (branching) structure and model for species. But this will have to have three axes – two for geographic space, and one for time. This is realistic, and far more so than the pressure that is exerted to produce the artificial two-dimensional cladograms botanists seem to favour and which the nomenclatural system caters for. ♦