Printed in Aloe 12:89 (1974).

M.B Bayer, Karoo Botanic Garden, Worcester.

The ‘retuse’ haworthias are among the most fascinating of the genus and therefore Colonel Scott’s recent revision is of particular interest. This work…‘A revision of the genus Haworthia, Section Retusae” was published in ALOE, Dec.1973 and forms a new taxonomic record of the species involved. The object of the present paper is to examine the validity of this record particularly in the light of past history of Haworthia. A considerable literature on Haworthia is now available much of which points to the problems likely to be encountered in the group. Much of it also points to the consequences of inadequate species concepts for the group.

Prior to Scott’s revision, Jacobsen (1965) listed some 30 species in the section Retusae Haw. The problems in connection with the systematics of this group to which Scott refers presumably have arisen from the application of these 30 names. Application of existing names being essentially a problem of relating these to field populations by recognition of different populations and entities in a taxonomic hierarchy. Scott’s revision was undertaken with the expressed intention of “disclosing definite characters which would enable workers to distinguish between species, and to assist in the identifying of isolated plants”. It is also stated that “the variability of the species is partly the reason why it is not possible to construct a key . . . ”. Unfortunately Scott does not define the section Retusae, but from the text one can conclude that this is more-or-less as given by Jacobsen with the exclusion of H. correcta VPoelln. and the inclusion of H. laetivirens Haw. and H. caespitosa VPoelln. Scott also includes H. serrata Bayer and H. pubescens Bayer which were not assigned to any section when described. The word ‘retuse’ was originally used in reference to the recurving, apparently truncated end-area of the leaves and Scott offers no explanation as to why he includes species which have erect or incurved leaves, with no distinct end-area (e.g. H. laetivirens, H. pubescens), although the writer does not question the validity of so doing. The writer’s experience is that this may be a variable character in some species such as H. schuldtiana VPoelln. in which retused, erect, or incurved leaves are characteristic of different populations within fairly close geographic limits.

Of the 30 names listed by Jacobsen, 18 are by von Poellnitz the German botanist. The typification of these species is of considerable relevance and it is difficult to understand why Scott invokes the writers authority in this regard when he himself claims to have worked at the Berlin Herbarium where von Poellnitz’ types were purported to be. The passages in Scott’s article on p.14… “It it well-known . . . degree of certainty” refer to von Poellnitz’ species and are taken from the paper “Natural variation and species delimitation in Haworthia Duval …1. H. reticulata Haw.’ (Bayer, M.B. in Nat. Cact. & Succ. J. 27: 51, 1972). Unfortunately this passage is not entirely correct and the subject of typification of von Poellnitz’ species will be dealt with elsewhere.

The crux of Scott’s revision is the typification of H. retusa (L.) Duval on the basis of leaf-tiers, and the key to the species revolves on this character in addition to the angle at which the leaf end-areas are retused. In Haworthia the leaves are arranged in a continuous spiral and it is known that vertical and diagonal leaf tiers are a phenomenon related to this construction (see Aloe, 11 (3): 31, 1973). It is rather difficult to follow Scott’s elaboration on leaf tiers which in totality proves to be irrational. It is quite clear that Linnaeus identified his Aloe retusa with the Commelin and Tillius illustrations which, Scott points out, show plants with 5 tiers of leaves. It is not clear though that Scott actually recognises these as horizontal tiers. The paragraph on p.11…”In the field, plants with less than five tiers of leaves, have four or five leaves comprising a tier, while plants with five tiers of leaves have six leaves in a tier. It is the author’s opinion that Linnaeus was therefore referring to the five tiers of leaves of his species, rather than the number of leaves.” is incomprehensible. Linnaeus described Aloe viscosa using the word ‘trifarium’ to refer to the three vertical leaf tiers in this species, and there has never been any doubt that the use of ‘quinquefarius’ referred to anything but the same vertical or subvertical arrangement in H. retusa. A. retusa as described by Wilidenow is simply a record of Linnaeus’ species as is the subsequent listing by de Candolle. Redoute’s plate is a beautiful illustration of a plant with five vertical leaf tiers, but here Scott counts three leaves in the horizontal tiers and refers to the plant as three-tiered. This is the eventual basis for the recognition of H. solitaria as a discrete species. Salm Dyck’s t.3 of H. retusa which Scott claims to be four-tiered (p.37) is both described (and illustrated) by Salm Dyck as ‘quinquefarius’. Similarly Salm Dyck’s t.2. of H. asperula Haw. is selected by Scott as the type for a four-tiered species despite Salm Dyck describing and illustrating the plant as ‘quinquefarius’ (five-tiered).

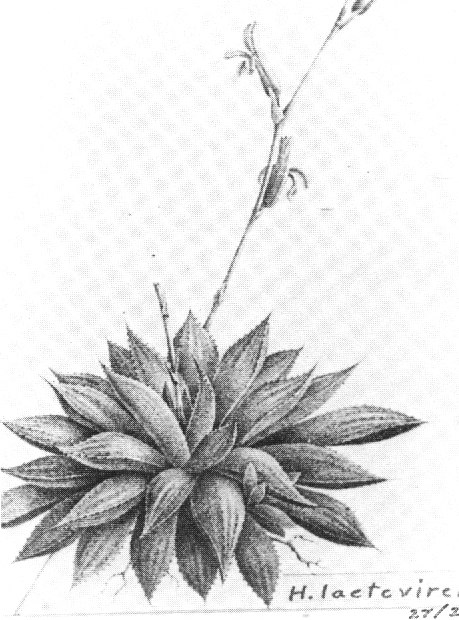

The map ‘Oudtshoorn SE 35/20’ issued by the Trigonometrical Survey Office in 1929, shows the Pogha hills to be west of the Gouritz river and north of the Langeberg mountains. Despite the significance Scott attaches to the discovery of a five-tiered plant in these hills, he does not cite a single specimen of H. retusa from that area. His citations are all south of the Langeberg. If so vital to the argument it hardly seems necessary to have invoked the Schryver expedition as Scott also states of the SW Cape “where a wide range of plants with different numbers of tiers may be found”. Scott reduces H. laetitvirens, Haw. H. turgida Haw. and H. caespitosa VPoell. under his ‘H. retusa’. However, there is no real relation between Salm Dyck’s illustrations of Haworth’s two species, H. caespitosa from the Tradouw Pass (type locality fide G.J. Payne — private communication) and H. retusa as illustrated by Commelin and Tillius (the former, H. laetivirens and H. turgida are described and illustrated as ‘multifarius’, see figs. I and 2). There is also no logical connection between Salm Dyck’s Aloe retusa, t.3. and Aloe turgida, t.5. It is obvious from this discussion that Scott’s concept and use of leaf tiers is irrational.

The angle of retusion is similarly inadequately dealt with and is untenable as a keystone of the revision. Scott does not indicate whether angles are to be measured from the vertical axis of the whole plant, or from the longitudinal axis of the individual leaves. Scott defines H. retusa as having…”the end area recurved at an angle of 60—90° (p.37)”, but in the key as 30—60°. The photograph shows a plant with some leaves retused more than 90° to the vertical. The pictotype has some leaves retused to at least 90° to the leaf axes and far more to the vertical. Similarly of H. mirabilis Haw., which is keyed on leaves retused 30—60° but described as having leaves retused between 60—90°. So, however intended, this character is dealt with inconsistently and in contradiction.

On the positive side it may be suggested that Scott has subconsciously used total number of leaves and degree of ‘flatness’ across the top of the plants in framing his species concept. The writer considers that this to a degree is feasible, but nevertheless still does not explain curious typification and assessment of the species. The individual species accepted by Scott can be further analysed to determine if, despite an irrational prologue and unworkable key, these can be recognisable and correct. This is as follows:-

1. H. comptoniana Smith. Scott’s illustration is Smith’s original photograph of the type GGS 3433. This species can be located in the field, but in the two collections at the Karoo Botanic Garden consisting of 19 plants, only one specimen has leaf margins serrulate. Thus Scott’s key is unworkable for this species. In any event it appears from field observations that this element varies continuously with H. picta VPoelln. (now H. emelyae) and very likely with H. willowmorensis fide Scott (the latter probably a synonym for H. mirabilis).

2. H. dekenahii G.G. Smith. Field examination by the writer does not tally with Scott’s observations. In his discussion Scott tacitly recognises a distinction between H. turgida and H. retusa. The farm Draaihoek is also the locality for H. turgida var pallidifolia G.G. Smith but it does not grow with H. dekenahii. The two localities are about 1 km apart and the distinction between the plants at these two sites is apparently further evidence of ecotypic differentiation. Scott places the entity pallidifolia under H. retusa. At the type locality for H. dekenahii var argenteo-maculosa Smith, only very isolated plants agree with Smith’s description. The bulk of the plants would fall under Scott’s concept of perhaps H. solitaria Smith.

In discussion Scott emphasises that the species was felt to be different to H. mutica Haw. partly because it grows in rock crevices. In the passage on p. 30 …”has located H. mutica at several places… are still visible”, Scott has been less than honest in ascribing the finding to himself. This is a direct transcript from a letter by the writer to Scott dated 28th July 1971. In a reply dated 11th Nov. 1971, Scott admits that the only locality on which he now based a revised concept of H. mutica (cf J. of S. Afr. Bot. 36; 287, 1970) was the one shown to him by the writer 24 km north of Bredasdorp (cited by Scott in his revision as ‘20 km SW Swellendam’ ?). Here H. mutica grows on a low clay bank in contrast to all the other localities known to the writer where it is in shale (i.e. rock crevices)..

3. H. foucheii VPoelln. Here von Poellnitz cited the type locality as “Grootvlei” 3 km N of Riversdale.’ Scott cites the locality as ‘Blinkbonnie’ and it would help to know that this is the actual farm where Fouche originally collected the plants. Scott describes this ‘species’ as 4-tiered (using his interpretation of horizontal tiers). Figure 1 is of a plant collected at the type locality having 5-tiers (the five vertical tiers of the true spiral leaf arrangement). Many specimens here are indistinguishable from plants growing at the locality for H. geraldii even to the point of forming large clumps.

4. H. geraldii Scott. It must be noted that this ‘species’ was originally collected by J. Dekenah who also claims to have shown the locality to Scott. Smith’s field records cite Dekenah’s collection ‘GGS 5377… on a dry and stony hill, under bushes in clusters up to 6 rosettes’. Scott uses these exact words in describing the species ‘geraldii’ and goes on to say…”readily and easily identified by the large clusters it soon forms” and “most proliferous of all”. In the field the clusters are immense with considerably more than 6 rosettes, but H. foucheii from the nearby type locality may also form large clusters. There is a population less than a kilometre west of H. geraldii which is also very proliferous, but a much smaller darker element which may perhaps agree with H. asperula (actually now H. magnifica). Field examination does not suggest that there is any basis for separating H. geraldii and H. foucheii, and other populations along the Kafferskuils (now Goukou) River suggest continuous variation with H. longebracteata Smith (now H. turgida). The writer would ally all three elements with H. retusa.

5. H. mirabilis Haw. Originally described as ‘quinquefarius’ (five-tiered), Scott describes and keys out a four-tiered species. The passage on p.25 relating to H. badia VPoelln. “s no more. . . are evident” is a direct transcript from a manuscript the writer sent in courtesy to Scott and actually referred to H. mundula Smith. Despite listing H. serrata Bayer under H. asperula on p.17, Scott disposes of the species as a synonym of H. mirabilis. The reason for this is that in the description, the author of the species likens it to a species taken at the time to be H. triebneriana from the Ladismith area. H. serrata more correctly belongs with H. heidelbergensis Smith.

6. H. magnifica VPoelln. Keyed out with leaves retused 30-60° and leaves in 2—4 tiers, the photograph (p.26) shows a plant with five distinct vertical tiers, and the description reads…”leaves recurved at about 90°”. In the writer’s opinion, the affinity of this species should be sought in H. asperula fide Scott.

7. H. nitidula VPoelln. The type is cited by Scott as…”Worcester: 3km N Worcester Maj. H. Venter …” and a neotype selected. The type must be the photograph extant in the Berlin Herbarium and von Poellnitz actually cites…”in the environs of Worcester, Caledon, Bredasdorp, and Robertson, without precise locality, Maj. H. Venter 15”. GGS 3907 is listed by Smith as ‘H. nitidula Greyton, Maj. H. Venter 15’. GGS 3904 is ‘H, nitidula Bredasdorp Venter 24’ and it is Smith’s photograph of this plant that Scott used to illustrate the species. Although Smith has a number of other citations which name specimens from Heidelberg as nitidula none are Venter Collections. He also listed specimens collected by Otzen and Reid from Bredasdorp. It seems obvious from these records that Venter 15 came from Greyton and it is easy to reconcile von Poellnitz’ type photograph with H. mirabilis which occurs both there and at Bredasdorp. There is therefore no connection with Smith’s H. longebracteata which the writer does not consider to be a valid species either.

8. H. mutica Haw. In originally describing H. springbokvlakensis Scott goes to some pains to relate H. mutica to plants collected near Mossel Bay by a Bruce Ramsay. This led to the correspondence between Scott and the writer concerning the relation between H. otzenii Smith and H. mutica. In his revision, Scott now places the Mossel Bay plants correctly under H. pygmaea VPoelln. but in synonomy with H. asperula. In illustrating H. mutica, Scott has used Smith’s illustration of the type of H. otzenii. There are however, problems relating to the typification of that species as firstly Smith has given an incorrect locality, and secondly the Curator of the NBG herbarium has recorded that types were never deposited. Scott interestingly cites the specimen Smith 7475 from both the NBG and Pre herbaria and the exclamation mark after NBG is presumed to confirm that the specimen was actually seen. The Director of the PRE herbarium informed the writer (private communication) that no specimen (of otzenii) was present there either. There is apparently now no basis on which to determine H. otzenii and a statement of these points are vital to any treatise purporting to be a framework for further study.

9. H. asperula Haw. Scott has included a wide diversity of species in synonomy under this entity. Preliminary observations by the writer suggest that

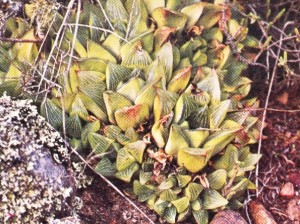

H. pygmaea belongs nearer to H. mutica on the basis of floral structure. H. pubescens similarly has a floral structure at variance with the bulk of the principal complex (H. schuldtiana VPoelln.). This species was recognised largely because of its apparent relation with H. herbacea (Lam.) Steam and this was clearly indicated in the original description. Whether H. asperula can in fact be directly linked with H. schuldtiana, or even H. paradoxa, is debatable. The photograph used by Scott to illustrate the species appears to be of plants from Tradouw Pass. The plants here are very difficult to relate accurately with either H. schuldtiana or H. retusa.

10. H. parksiana VPoelln. This species is keyed out and described as having leaves retused at an angle of 30 – 60°. It is clear from Smith’s photograph which Scott has used, that there is no distinct end area and that the older leaves recurve considerably more than Scott indicates. The type must remain the photograph extant in the Berlin herbarium.

11. H. picta VPoelln. There is some confusion concerning this species. H. emelyae VPoelln. is several times dubiously recorded in Smith’s notes, but there is one good record which states…”26 miles from Calitzdorp on the road to Vanwyksdorp” ascribed to the same Mrs le Roux mentioned by Scott. The writer has been shown populations in this general area which are readily identifiable with H. picta and varying continuously with that species. The name H. emelyae is thus apparently the prior valid epithet. Scott has excluded H. correcta from his revision which is a great pity as it originates from the collecting of Mrs Ferguson and Scott holds her collecting records. The correct locality for this species may reveal that it is also allied with H. emelyae. (see H. willowmorensis).

12. H. retusa (L.) Duv. In the writer’s opinion, Scott’s passage…”On high krantzes . . . no satisfactory way of subdividing the material into smaller units’ could have been more widely applied to include his concepts of H. solitaria, H.,geraldii and H. foucheii. There is little doubt that H. laetivirens can be identified with the many-leaved species found in the sandstone formations of the Langeberg mountains. Where this species descends to the formations of the Bokkeveld and Uitenhage geological series, profound ecotypic differentiation occurs. There is thus quite correctly ‘a bewildering range of plants’. (Scott had effectively transposed the conventional and correct interpretations of H. retusa and H. turgida).

3. H. solitaria Smith. Scott writes of H. mutica…”margins smooth as compared with the tubercled and toothed end area and margins of H. soltaria”. H. solitaria is keyed out on one lead…”end area of leaf not papillose”. It is described by Scott as having…”end area . . . rough with small concolourous tubercles”. . In essence there is no real distinction seemingly between Scott’s solitaria and Salm Dyck’s H. asperula Haw. which Haworth any way allied to H. retusa.

14. H. springbokvlakensis Scott. This species is correctly recognised as a good entity but the writer does not agree with Scott’s conclusion that it does not resemble any described species in the Retusae. Collections have been recorded in the Oudtshoorn area which do relate with the peculiarly rounded leaves of this species and perhaps also to Scott’s version of H. willowmorensis. This is not a contradiction of Scott’s species but merely an additional comment.

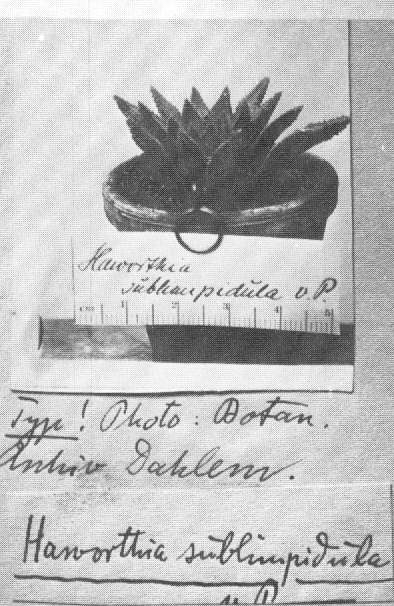

15. H. sublimpidula VPoelln. The type of this species should be the photograph in the Berlin Herbarium which was published with the description of the species. There is no evidence on the herbarium sheet to indicate that Scott saw it, and the photograph shows a plant with blunt sub-scabrous leaves. This is quite unlike the photograph of Smith’s 6566 (of the type of H. heidelbergensis Smith) which Scott uses to depict his concept. The writer has letters from P.L Meiring written to Long, Triebner and Herre which suggest that he was responsible for collecting the species in the Bonnievale area. Fourcade’s 172 of…“H. sublimpidula ex Winton’s nursery-agrees with fig. in Sukk” does in fact agree with that, and this is at variance with Scott’s concept of the species. Winton’s Nursery was owned by Hurling and Neil (Hurling the cited discoverer of the species) and Fourcade’s photograph must be of a co-type. Strangely enough Scott does not cite von Poellnita’ article in Sukkulentenkunde (1939) (in which both H. sublimpidula and H. willowmorensis VPoelln. are figured) under the former species, but does so under the latter. It is unlikely that Scott saw the reference cited, as plants agreeing with the description and illustrations of H. sublimpidula noted above are present in the Bonnievale/Robertson area. These are identifiable with H. schuldtiana and perhaps H. guttata Uitewaal.

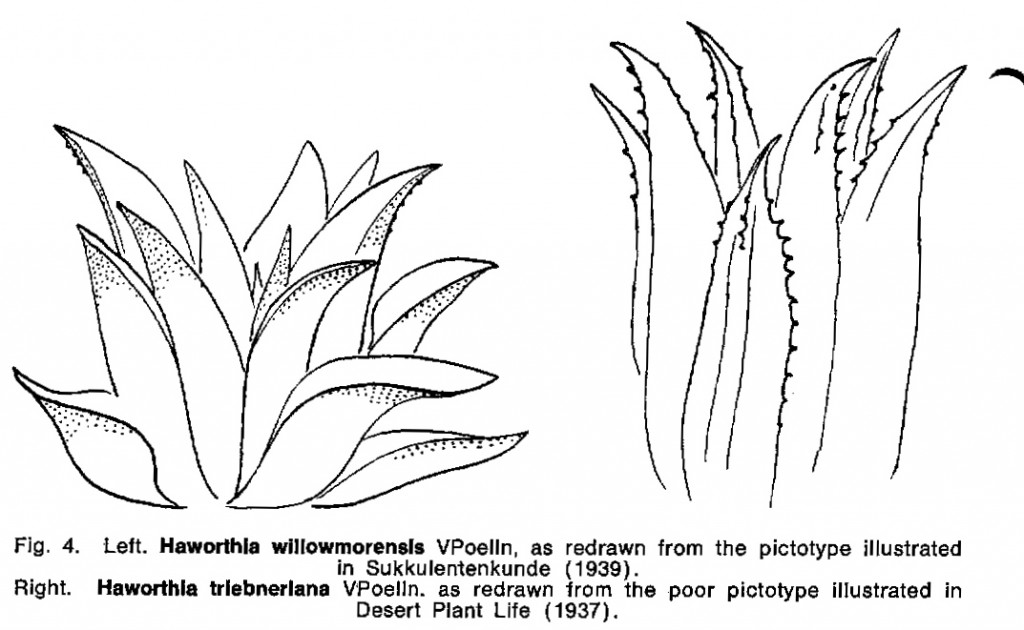

16. H. willowmorensis VPoelln. The type of this species is cited by von Poellnitz in Fed. Rep, 41:210 (1937) as…”Cape; Willowmore, Mrs Helm, coll. Triebner 840”. Scott cites the type as Triebner 978 collected by Mrs Blackburn. In personal communication with the writer, Mrs Helm could not recall collecting in the Willowmore area at any time and did not even recognise the name of such a species. Von Poellnitz’ illustration is very like some of the forms of H. mirabilis. It should also be noted that H. triebneriana which from a photograph of the type is also assignable to H. mirabilis, was said by von Poellnitz to have been collected by Mrs Helm at Strydomsvlei. This was a plant passed on by Triebner (841) and bearing a consecutive number to H. willowmorensis. The writer has searched fruitlessly for any semblance of these two species in the Willowmore area and concludes that Triebner perhaps transcribed Stormsvlei as Strydomsvlei. In this case both species can be better allied with H. mirabilis. Finally Scott’s illustration and description of H. willowmorensis bear no relation to the original. This appears to be a new element which can be reconciled with other collections by the writer in the de Rust/Oudtshoorn areas, and by use of the name asperula by von Poellnitz in reference to plants from this area. Finally floral character does not support the view that H. atrofusca can be associated with plants collected by the writer allied to Scott’s concept of H. willowmorensis. (I am not sure that I can properly explain away the confusion in respect of this issue which involves H. picta and H. emelyae as well. Scott confirms Mrs. Ferguson’s note that H. emelyae was collected by a Mrs Le Roux of VanWyksdorp and thus my contention that the correspondence in Smith’s records that Mrs. Le Roux also collected it there are valid. Hence the name emelyae precedes correcta from the same area. Scott’ specimen citations for his willowmorensis include emelyae, bayeri and magnifica var atrofusca as I treat them. My reference to “a new element” is actually to H. bayeri which I later included in an expanded concept of H. emelyae.)

17. H. rossouwii. The writer has previously applied this name to plants collected 12 miles N of Bredasdorp for two reasons:- firstly this is a site that Payne (private communication) could recall to have visited with Rossouw, and secondly von Poellnitz cites the same collecting number (Triebner 1059) as the type for H. altiinea var. bicarinata. At Payne’s locality there are three elements which the writer hopefully tried to reconcile with either of these two names. However, Scott must be taken to be correct in locating H. rossouwii south of Bredasdorp where H. triebneriana var sublineata VPoelln. occurs. This is a synonym under H. mirabilis but there are a number of discrepancies in Scott’s citations of types under this species including the one for sublineata. Payne’s written collecting records indicate that the locality was the mountains south of Bredasdorp. He has Triebner’s number 1106 attached to this record and Von Poellnitz cites this same number with the comment ‘grows between cliff rocks’. Scott cites the same number and adds the information ‘4 km north of Bredasdorp’. There is no record of the element concerned in the Berlin Herbarium, nor is there any suggestion by Scott as to where the additional information derives from. (Recent field work has located rossouwii at three localites close northwest of Bredasdorp and it is patently synonymous with my later H. serrata).

18. H. notabilis VPoelln. Scott claims to have investigated this species in the field and rejects it as a hybrid between H. arachnoidea (L) Duval and H. reticulata. The writer is very familiar with the locality at Wolfkloof, Robertson and has been unable to locate H. arachnoidea (=H. setata Haw.) at this specific site. However, H. notabilis does occur at several other localities as clearly habitat specific populations, and at Buitenstekloof, Robertson, both H. arachnoidea and H. reticulata also occur. Here each of the species occupy different ecological situations and they flower: H. reticulata — late winter, H. arachnoidea early summer, and H. notabilis late summer. H. notabilis does not show any characters which suggest shared genetic elements of the other two species. If, on the other hand, it is considered over its entire distribution range, H. notabilis can be recognised as an ecotypic element of H. schuldtiana. Hybridisation is a term which is rather loosely used (by the writer too) to cover problems of variability. In the writer’s experience, only once has a hybrid been found positively involving a member of the Retusae. This was the hybrid H. laetivirens x H. floribunda VPoelln. Scott several times uses the words ‘hybrid segregation’ whereas hybridisation is an introgressive process for which little factual evidence exists. (I was not aware at the time that Scott was using arachnoidea where I was using herbacea and he was thus justifiably confused by the complex interaction of maraisii, reticulata and herbacea).

Conclusion:

The history of Haworthia is unfortunately one of controversy, and this paper further demonstrates the problems which can arise from ill-considered and inadequately researched publication. (Which is still rife. In scaning and editing this article together with other earlier articles of mine, I think it is absolutely unacceptable that other writers have not properly and publicly considered the issues which I have raised about workable and rational species concepts. It is inexcusable that present day writers are simply the repeating the same mistakes that led to the kind of confusion this article illustrates.) Opinion is involved in any decision making process but informed opinion based on factual evidence is essential in taxonomic work. The writer does not suggest in the least that there is a simple solution to taxonomy in Haworthia but with due respect to Col. Scott his revision must be rejected as fallacious. The nomenclatural changes proposed therein must therefore be formally invalidated. It is shown in this paper that the basis of Scott’s species concept viz, leaf tiers and angle of leaf retusion is invalid. The problem does arise as to how the entire complex should be handled. It is obvious that the method of describing species from average specimens as G. W. Reynolds did in Aloe is both obsolete and inadequate. Most Haworthia descriptions are padded out with irrelevant and useless data such as…”leaves, spirally arranged”, “peduncle simple terete” or include detailed dimensions of a single inflorescence taken from a single flowering plant. To be understood, the Retusae will need to be treated as an ecological continuum, completely abandoning the present artificial sections and including species such as H. herbacea, H. reticulata, H. floribunda and H. variegata Bolus. A further essential is the adoption of a realistic and practical species concept where the ‘aggregate’ is used to avoid artificial strictures of the species/subspecies categories. Some flexibility is needed to retain entities in an information retrievable manner until a better classification is achieved, where phylogenetic and evolutionary trends can begin to be guessed at. For this to be done, use will eventually have to be made of all morphological and physiological characters comprising the complete plant.

Fig. 4. Left. Haworthia willowmorensis VPoeIIn, as redrawn from the pictotype illustrated in Sukkulentenkunde (1939). Right. Haworthia triebneriana VPoelln. as redrawn from the poor pictotype illustrated in Desert Plant Life (1937).