M. B. BAYER

Karoo Botanic Garden, National Botanic Gardens of South Africa

Published in CACTUS & SUCCULENT JOURNAL (U.S.), Vol. XLVI, 1974

‘Out of Africa always something new’ is an expression the reader may excusably believe no longer applicable in the case of Haworthia. However, in the last 8 years no fewer than seven new Hawrthia species have been described. Three of these are by Col. C. L. Scott, one by Dave Hardy and Mr. Obermeyer and three by the writer. Many species have been deleted in the past two years and many more are destined to a similar fate—but it is also likely that new species will still emerge.

The real problem in Haworthia has been and still is the question of deciding just what constitutes a species, as this concept is rather difficult to define even for the most general application. A species is obviously not one single plant, but an aggregate of individuals which look alike and comprising a population or series of populations adapted to, and propagating in particular habitats. A species should not be described without duly considering this. In Haworthia one cannot generalize too much about what a species is either, as in the three subgenera (and add Astroloba and Poellnitzia if some authorities exercise their will) one finds apparently quite different systems in operation. Peter Brandham of Kew has recently demonstrated that entire and even widely separated populations of H. reinwardtii may comprise or contain genetically identical plants. This shows this species does propagate vegetatively and a species concept here may be quite unfitted for other species such as H. lockwoodii which do not propagate vegetatively in nature. In many cases the writer has found odd populations which are each quite distinctive and yet which must be outliers of more widely distributed and commoner species. If these are all to have names, taxonomy in the group may become quite unmanageable. It thus seems far wiser to adopt a rather broad species concept and rather include such populations under their apparent points of origin—if it is possible to do this.

H. geraldii Scott was described from the Riversdale area and is found just north and northeast of the town. The writer has only visited the northern locality where the plants do present a remarkable sight. Huge solid clusters of up to 1/2 meter or more in diameter containing 60 or more large rosettes slightly raised from the ground—beautifully colored greenish-yellow, with prominent face lines on the heavy thick leaves. About 200 meters to the west is a smaller population of another plant which appears to have some affinity to H. asperula (synonymous with H. schuldtiana?). This latter plant seems to breed true from field seed, which may seem rather odd when one considers how close it is to H. retusa and H. geraldii. A few kilometers east is the site of H. fouchei, and still further east in the Kafferkuilsriver one finds forms which lead on to H. longebracteata from the lower reaches of this river. The story does not end there, because westward from Stilbaai andsouth of Riversdale one finds populations still very near to H. longebracteata, until at the Duiwenhoks river at Heidelberg one comes to the source of H. nitidula. North of Heidelberg one finds a most classic example of ecotypic transformation in Haworthia. In the sandstone formations are typical H. laetivirens, in theshale a little to the south, the plants are larger and unspined until in the conglomerate at Heidelberg there is a motley complex of plants tending to H. nitidula (and hybrids with H. floribunda!). It is certain that all these populations must be regarded as components ofone species and that names such as H. fouchei, H. longebracteata, H. nitidula and also H.geraldii cannot rationally be maintained. Species such as H. turgida, H. dekenahi and H. caespitosa may also yet be excised. However, this is an extraordinarily difficult complex and good facts are really needed on which to base sound argument.

H. springbokvlaktensis Scott is unquestionably a good species. Known for many years and recognized as H. mutica by collectors such as Major F. R. Long, W. E. Armstrong and other enthusiasts of the pre-war period, Col. Scott has correctly separated this species at Springbokvlakte. Growing together with Lithops terricolor in the typical sandy Karoid area east of Steytlerville, it is a most striking plant. The very rounded leaf tips and thumblike leaves, the purplish, translucent face area and darker face-lines make this a most attractive plant. It does not seem to be very plentiful and is seldom proliferous. More than one locality is known and evidence suggests that it is to some degree intergraded with the H. emelyae complex around Oudtshoorn. At Uniondale one finds plants which also indicate affinity with H. comptonii which in any case may best be regarded as a near ally of H. emelyae. H. mutica is now well-known to occur in the Bredasdorp/Caledon area (H. otzenii is synonymous here)—inclined to a purplish hue with unpointed leaves, it does extend eastward toward the notorious Riversdale area. It is very difficult to convincingly separate H. mutica from H. retusa and even from H. pygmaea at Mossel Bay.

H. baylissii Scott is from Oudekraal in the Somerset East district. This species has not been seen by the writer in the field and with two very disparate collections from that locality as well as deviations from the description, doubts as to its validity must exist. A collection at Kirstenbosch apparently received from Col. Bayliss (the collector of the species), is clearly H. angustifolia but with shorter, thicker leaves than normally encountered in that species. The locality is a little far west for H. angustifolia (not to be confused with H. monticola from the southern Karoo!) but the plants do also have the silver flecks as in co-types of H. baylissii, also in cultivation at Kirstenbosch. The main distinction of H. baylissii was said to be the recurving leaves, but this is not a stable character and none of the plants in cultivation either at Kirstenbosch or the Karoo Garden have this character. Why this species should have been placed in the section Muticae really serves only to underscore how abysmally weak the sections actually are. This section was originally created by Berger for H. reticulata, and eventually contained ‘H. hurlingii, ‘H. haageana’, ‘ H . intermedia* (all synonymous now) as well as a few other species including H. caespitosa. H. baylissii has quite patently no close affinity, difficult and obscure as Haworthia taxonomy may seem to be, with any of these species and until better understood should be considered close to H. angustifolia, but not necessarily to all species in the section Loratae.

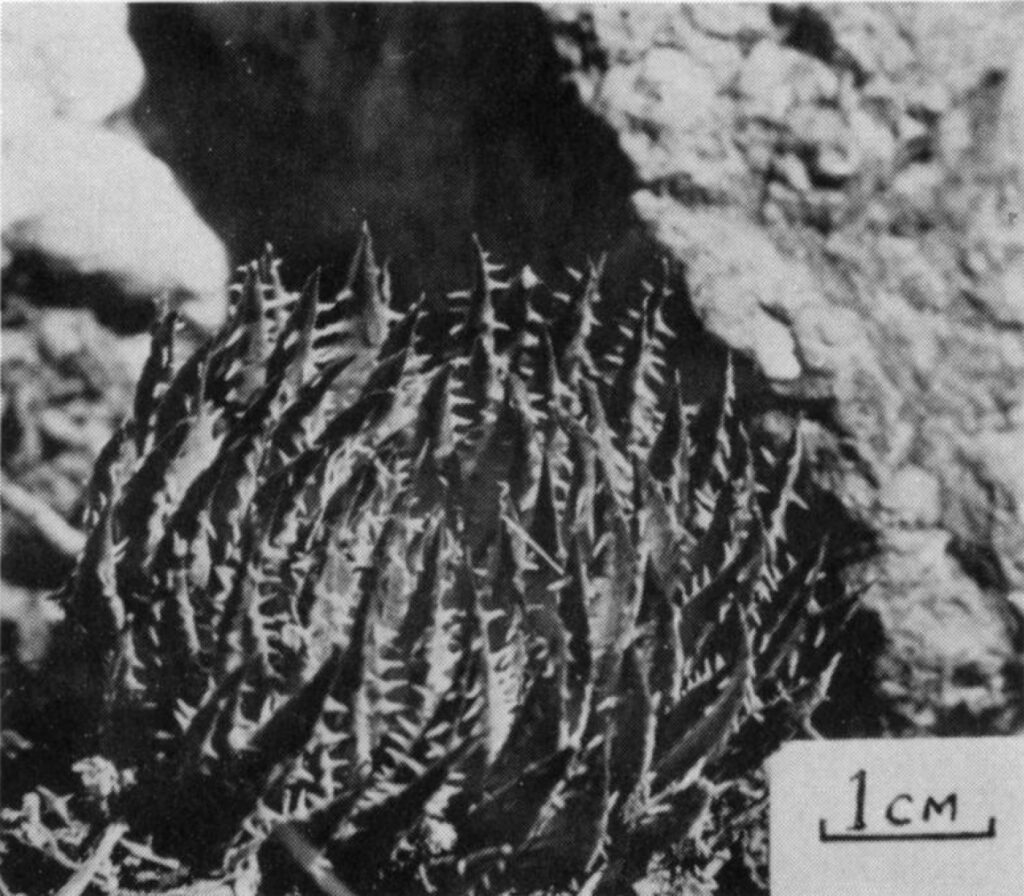

H. koelmanniorum Obermeyer and Hardy was described from Groblersdal in the eastern Transvaal and this is far to the northwest of the nearest species, H. limifolia. The differences by which it was first separated from that species are quite invalid. As far as suckering is concerned, the different forms of H. limifolia do not all sucker freely, if at all; H. limifolia does not have a significantly different base to the rosettes, and if it did, would probably require separation at generic level! The tubercles on the leaves of H. limifolia vary enormously over the distribution range—from colorless, wavy, undulated ridges, to prominent white bars—from small, concolorous tubercles to large, raised pustules. The difference in phyllotaxis is also fallacious, as any admirer of the arrangement of spines on cacti will be quick to grasp. A l l Haworthia have their leaves spirally arranged and H. limifolia together with H. tesselata are rather exceptional in that the angle of leaf divergence is rather high, in the vicinity of 160°. This means that the two primary counter spirals are more readily apparent than the three secondary spirals. When grown together with many other collections of H. limifolia, the writer can see no exceptional reason for separating H. koelmanniorum from that species, other than the color being a deeper, translucent gray-green and the leaves bluntly tapering. The flower in H. limifolia is rather variable and there is no evidence here to suggest the H. koelmanniorum is distinct. Floral characters in the whole subgenus Hexangulares are, however, rather much of a muchness and not very helpful. H. tuberculata, together with H. starkiana, does have unique floral characters and to suggest the H. koelmanniorum has an affinity here is to do justice to neither species and offend the small differences which are of taxonomic value in the genus. Geographically speaking, the species is of note but it is not correct to talk of ‘outliers (of the genus) extending to Zululand, Swaziland and southeastern Transvaal*. It must be obvious from the above that probably only one species, H. limifolia, is involved, but perhaps sufficiently differentiated for local populations to be recognized at subspecies level.

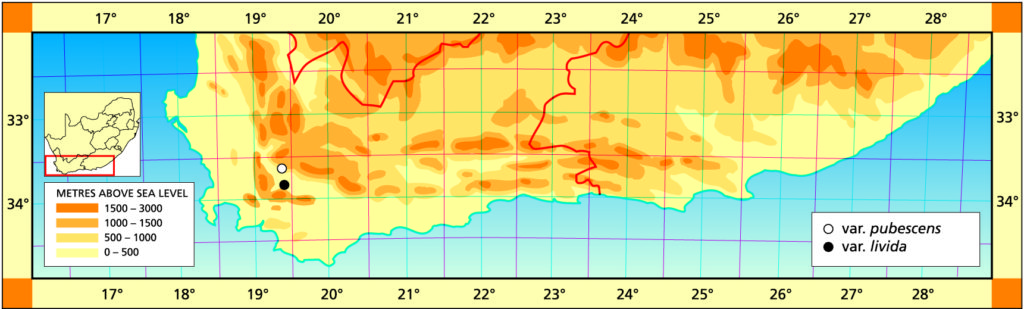

H. pubescens Bayer is, with the next two species, a ‘creation’ of the present writer—and perhaps enough said! There is no doubt that this species has an affinity with the very difficult and variable H. schuldtiana complex. However, it is equally allied to H. herbacea.

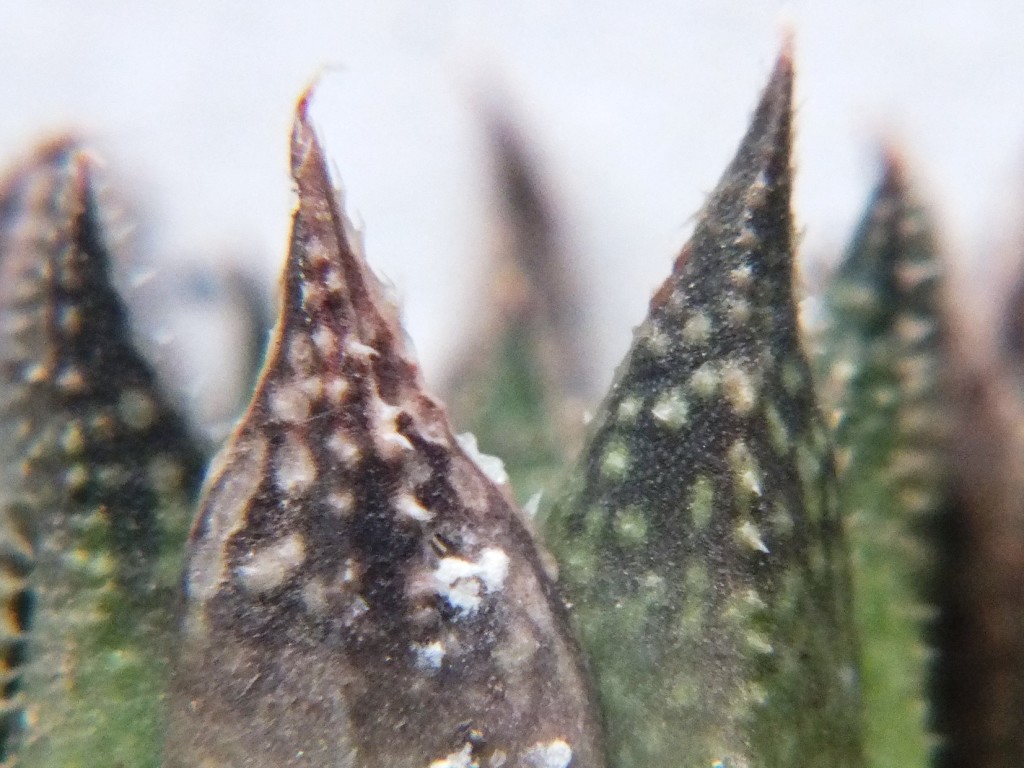

Important distinctions include both vegetative and floral characters, flowering times, locality and ecological associations—and the author is not concerned with single plant characters or collections. H. pubescens comes from a very dry area south of Worcester and is hard to grow, requiring strictly winter watering and no direct sunshine. A well-grown plant is a pleasure to behold—the whitish pubescens on the dark green background give the incurved, abruptly pointed leaves a velvety appearance.

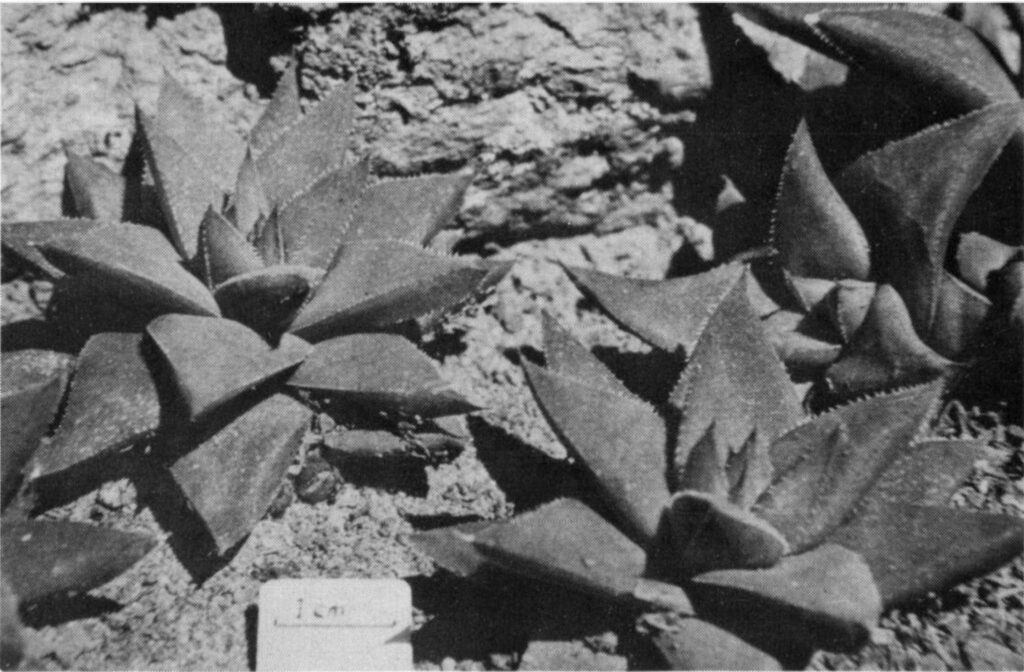

H. pulchella Bayer, nom. nov. in manuscript, can also be put in the gem category. The small, sparkling spined, emerald ball is the real jewel of the Karoo garden collection. First known to the writer through its discovery by the late Mr. Roy Littlewood and the recollected by Mr. F. J. Stayner, this species is from the very dry, desolate hills of the Touws River area. Its affinities are doubtful and the flower is as ordinary as that of an haworthia can be. Associated species do not give any leads either and the nearest species geographically speaking are H. setata and H. tessellata. Much further away are H. wittebergensis, H. lockwoodii and H. margaritifera. If the writer was forced to select a near ally, it would be H. monticola on the basis of floral similarity.

H. serrata Bayer is no less contentious than H. pubescens. Occurring at several localities within a relatively small area, this species is one of the affiliates of the Heidelberg complex. In some forms the leaves are incurved, suggesting a robust plainly marked specimen of H. herbacea, while in others the leaves recurve as in H. heidelbergensis. The flower is characteristically rather bright green in the veins and does not have the closely plicate tips of the upper, outer tepals as does its expected relatives. That many leaves, among other considerations, remove it from H. retusa, and it must have close ties with H. rossouwii at Bredasdorp. H. serrata demands recognition, but how best to express its distinctiveness in among several almost unique populations in that area still eludes.

In concluding it may not be necessary to say that taxonomy in Haworthia has passed beyond cursory examination of the simple, external structure of the plants. What is really needed is some good morphological study aimed at analyzing characters which might be of better value in separating and circumscribing the species. Nevertheless, some kind of structure is necessary even to base such a study on, and any contribution must be gratefully welcomed.