An edited copy of an unnecessarily harsh letter sent to Ingo Breuer, which includes a letter sent to Mr Harry Mays, editor of Haworthiad. That letter commented on an article by Breuer published in Haworthiad and my reaction to it. The comment was not for publication and was a request for assistance in countering bad and inaccurate writing. I will make any apology for any offence and hurt I have caused by writing in this way, but I cannot apologise for anything which is true outside of my own thoughts:-

Author Archives: Bruce Bayer

Addendum 6. A review of the book ‘The world of Haworthias’ Vol.1 by Ingo Breuer, Niederzier, Germany,1998.

In my Haworthia Handbook (1976) I wrote “In the by now vast and inconsequential literature on Haworthia…”. Breuer’s book is mostly an extraordinary and wonderful index of this literature and he advises us that “a hint on cultivation, caption or simple mention of a name” are excluded. I did not fully realise how much trivial literature there was. What I looked for in the book was its promise for Haworthia, and evidence that the author understood the literature he has so vigorously tracked. In 1983 I took Haworthia as far as I could with the data and material that was available, and had some well-developed ideas as to what the next step was. As it happened, Col. C.L. Scott’s book was published (1985) which inaugurated a tradition in Haworthia in which the scientific principle of organised scepticism is lost. I wrote several articles trying to clear the cobwebs of uncertainty and confusion that this tradition embraced. Apparently to no avail. I am already aware of several articles which Breuer has authored and which have been the subject of some criticism. For me they sow the seeds of concern for the future of Haworthia.

Addendum 7. Is classification science or art?

A manuscript for the journal Asklepios.

Is classification science or art? Part 1.

The common reaction and assertion is that classification (of plants) is a matter of opinion. It is also often stated to be an art, and even the late Prof.A. Cronquist in writing a book on the principles of plant taxonomy, describes it as ‘artful science’. John Lavranos in a letter (1998), and an anonymous referee for SA Journal of Botany in an assessment of a manuscript, state that taxonomy is to a degree ‘art’. It is necessary to examine this belief because it is intrinsic to our understanding of plants, the names we use for them and how we communicate about them.

Addendum 8. A letter of disquiet to the Haworthia Society.

1999-10-21

The Chairperson

Haworthia Society

79 Osborne Road,

Sheffield

S11 9BA

Att.: Mrs Dorothy Minors.

Dear Mrs Minors,

Thank you for your very kind and considered reply to my letter of 22scd Sept. My biggest regret is that I cannot put the names and faces together of all those real people that I met, and still meet, in my dealings with Haworthia.

I hope you have read the article I wrote which appeared in Asklepios recently. Science is actually at a bit of a crossroads and this partly accounts for my own desperation and concern for what is true. Science rests on classification. Its fundamental weakness is its classification of creation into “conscious” and “unconscious”, and it deals only with the latter. Science and materialism have become inseparable and falsely so. Knowledge cannot be based on such a basic and false hypothesis that creation is a mindless chance event. There is powerful evidence of an alternative hypothesis in a vast library of books and everywhere in human history. What we presume to be science is materialism and there are profound cracks in the foundation.

During the last two years since I wrote Haworthia Revisited, I have done some very intensive revisiting and have some extraordinary material. My problem is now to find an editor who is sympathetic to the position I find myself in. Neither Aloe nor Haworthiad provide an environment in which I feel that I can write with diffidence and reservation; and that the audience is adequately and correctly informed to digest and judge what I have to say. So it becomes pointless to say anything at all, and I am faced with the same problem that G G Smith ended up with i.e. invalidation.

Addendum 9. Observations on cytology as a character source in Gasteria.

Introduction:-

The classification of Aloe, Haworthia, Gasteria, Astroloba and smaller related genera is in the public domain in the sense that there is an immense public interest in the collection and cultivation of these plants. Unlike more general horticultural elements, succulents plants are of interest to collectors as natural “species” and hence the taxonomy and nomenclature are central to the activity and communication which takes place in the collector citizenry. Unfortunately the degree of interest and activity of competent (as opposed to trained) scientists (ie. botanists) has not reached the same degree and intensity. The need for information and classification has by default passed to non-scientists/botanists. A paper in respect of this topic is published in Asklepios (Bayer, Aug./Sept. 1999). This particular article is written to further examine the nature of the data obtained by scientists and presented as such to the amateur community. It is written particularly in the light of the conflict which has clouded the literature concerning Haworthia since at least 1947, and which continues unabated.

Haworthia maculata ↔ Haworthia pubescens, MBB8002 Cilmor

In Haworthia Update Vol 9 there is a report of a population MBB7997 identified as Haworthia pubescens from north of the Cilmor wine cellary. This is approximately 2-3km southwest of the type locality for the species. I noted that the plants have less spinuliferous leaf surfaces and there is a degree of surface translucens and maculation (spotting). I also presented 3 pictures of MBB7271 of what I identified as H. maculata from south of the Cilmor cellar. When I first visited this locality I had no problem identifying the few plants I saw as H. maculata on account of their marked spotting. However, on a recent visit we struggled to find plants at all and the few plants we found were too embedded in rock cracks to make any worthwhile identification. So we revisited the site to explore more extensively and located a large number of plants higher up and slightly west of our first sightings. These plants are illustrated here. They incline more to H. maculata than the plants at MB7997 and I have accessioned the population as MBB8002. There is the usual expected large variation in respect of superficial and observable characters. The plants can be proliferous and cluster, more so than at MBB7997. Similarly the leaves can have more translucens and even less spinuliferousness of the surfaces. Some plants have few and quite thick swollen leaves while others may have more and very slender pointed leaves. I have not observed the flowers and really do not expect them to make any difference to the problematic classification of populations that again are neither here nor there in a narrow concept of species. H. herbacea occurs at all four geographic positions at a radius of about 2km. At the brickfield to the northwest as well as just northeast of the Brandvlei Dam wall it is evident to me that there is a transition between H. maculata and H. herbacea. I did report the known distribution of H. maculata in Update 9. While there is no suitable habitat between Die Nekkies hills at the Brandvlei Dam and the Audensburg or Kanetvlei, there is unexplored suitable habitat southwards to Moddergat and Hammansberg. There is no evidence of H. maculata eastwards to where H. reticulata is known about 15km east on Ribbokkop. Westwards no Haworthia is known although G.J. Payne did inform me that he had observed plants in the hills immediately southwest of the Dam at the now submerged hot spring in the Brandvlei prison area.

The submitted pictures include two views. View 1 is looking north of east across the Breede River to the Sandberg where H. pubescens occurs. Its full occurrence on those low hills is not known and this I will explore soon. View 2 is looking eastwards looking at a Dwyka Tillite hill across the river in the upper right. We found no Haworthia on that hill although both H. pumila and H. herbacea are present on the smaller rise to the right and behind it – also Dwyka. H.herbacea is very abundant on a Dwyka tillite hill about 10km to the south. The corresponding hill on the left is Ribbokkop where H. herbaea, H. reticulata and hybrids are present, and H. arachnoidea also occurs. The limits of H. mirabilis are the higher hills in the background viz. Rooiberg, Gemsbokberg and those are Witteberg sandstones. ♦

Addendum Haworthia pubescens MBB8011, SW Sandberg

I need to point out that there is a still earlier article which covers Haworthia maculata (Haworthia maculata <–> Haworthia pubescens) that lays the basis for this discussion. In that article I note the position of the Sandberg to Cilmor and DeWetsberg and intended to include the Sandberg H. pubescens in that article. We could not get landowner contact and so that fell away. However, this problem was overcome and we first explored a Dwyka Tillite outcrop southeast of Sandberg. There is a vast accumulation of windblown sand on the first hill and we saw no Haworthia. There is a smaller hill further to the southeast that is also Dwyka and erosion exceeds wind deposition so smaller non-geophytes do quite well. We found both H. herbacea (see fig.1 MBB8014) and H. pumila there. From there we went to the southernmost point of the Sandberg. A misjudgment landed our vehicle in mud and the drama to get out limited the time we had to explore. We found a lone H. herbacea (fig. 2 MBB8012). Returning a week later we approached the Sandberg from the southwest, and almost immediately on reaching the top we found H. pubescent. Fig. 3 is a view towards Cilmor and DeWetsberg where the plants appear to be intermediate H. pubescens↔H. maculata. The picture is useful to get some idea of the role of geographic and geological considerations. The high mountains in the background are Table Mountain Sandstone and no Haworthia is known there. I am not certain that this is true and G J Payne did tell me that he had seen plants on the extreme lower right and south of the Brandvlei Dam. But also on the absolute distant and absolute left, is the Riviersonderend Mt. That is also TMS. The deep Wolfkloof Valley behind that is the locality for the much unexpected H. herbacea ‘lupula’. (These inverted single commas are not entirely necessary but I use them to underscore my informal use of names that have less reality. The var. lupula is real). The mountains ahead of that last line are Hammansberg on the left and the Moddergat to the right. Between there and DeWetsberg has not so far turned up Haworthia, but this is an exploration problem. Behind the DeWetsberg is also underexplored. H. herbacea does occur between DeWetsberg and behind the mountains on the low right just in the picture and also east of the brickfield out further right. H. maculata is only known in this area along the Nekkies north (further to the right) of the Brandvlei Dam just visible in the picture.

Prior to this exploration H. pubescens was to me only known from the northern part of the Sandberg that lies south of a road going eastwards to Eilandia between Worcester and Robertson. Here H. herbacea does occur on the lower northwest warm slopes. H. pubescens seems to occur only on the upper two ridges and H. herbacea is not known to intermingle with it. This is all Witteberg Sandstone that as a formation overlies Bokkeveld Shale and underlies TMS.

Coming back to the southwest corner of the Sandberg where we found H. pubescens. The plants seem very similar to the species as it occurs to the north. They were very cryptic and often in shady rock retreats where they were really hard to see. It was mid- to late-morning when we were there and the plants were not going to be better exposed as the sun moved further west. Although there was very suitable well-drained habitat lower down on the shaded east slopes, there were no plants and I speculate that this may be because the plants may need the cooling effect of wind movement up on the ridge. The pictures tell the story of variability in respect of a whole range of leaf and rosette characters.

It is worth noting fig. 43 of the dead remains of a plant under a clump of restioid. It seems that seedling survival is closely coupled to early protection giving rise to the concept of nurse-plants. Plants are often very difficult to find because they are so hidden beneath accompanying vegetation. But they do need light and the dynamics of vegetation growth and densification must have quite a big impact on the ageing and survival of plants. It raises again the question of how long do the plants live? For plants like Aloe ferox and A. dichotoma I do have a real experience of a lower limit of about 35 years and a top limit in the several hundred. In the field, the plants seem comfortably ageless.

The really interesting part is this. While I was busy tediously cleaning a plant to photograph it, Daphne called to me to come and see a lighter green plant she had seen. Moving in that direction I saw a plant that registered as H. herbacea but with some hesitation and doubt (see fig.4). I then went to see what Daphne had observed. They seemed less obviously H. herbacea but that seemed to be a logical and conservative opinion (see figs. 5-11). That was until Daphne found two adjacent rosettes at the foot of a restioid clump that left me in no doubt that they were hybrid H. pubescens/maculate (see figs 9-12). These were in bud whereas H. pubescens plants showed no sign of impending flowering. Note the buds are less well developed than MBB8014 further east, even if possibly insignificant. Going back to the other plants we confirmed my doubts. They were a lighter colour and apparently softer texture that we would have expected in H. herbacea. These were the only plants we saw in a space bridging the occurrences of plants of H. pubescens.

12-46 MBB8013 H. pubescens, SW Sandberg.

We did not explore the western slopes where habitat would have been more suitable for H. herbacea and I expect it does occur there. What puzzles me is that so frequently have I found very distinctive hybrids between species in close proximity and very seldom where the species are some distance from one another. I cannot say I have ever found a hybrid in the clear absence of both parents. The example of Astroworthia bicarinata at Lemoenkloof, east of Barrydale, may be an exception where only Astroloba corrugata (syn A. muricata, A. aspera) is present but H. pumila apparently not. Hybridization is thought to be an important element in the “evolution” of new species. I doubt this as it is quite evident that separation into two species is a pre-requirement. If new species have evolved in Haworthia by hybridization, how did they evolve as such in the first place? The answer to me lies in the continuities between populations. I observe, and have experienced of expected continuity between populations. While the Cilmor populations are thought to be H. pubescens ↔ maculata it cannot be said anymore that they are hybrid, or populations where the morph or drift to discrete elements has not reached a conclusion. The latter is more likely. As there is already apparent geographic continuity of H. maculata and H. herbacea, I was expecting some evidence of a similar relationship between H. herbacea and H. herbacea. So here it is. Hybridization as a factor in speciation in Haworthia does not seem to very likely. It confirms for me that there is a fractal “chaotic” order to species in Haworthia and the reality is that a view of many truly discrete species is a fabrication and a very ill-considered view.

Acknowledgement

We are always greeted with such kindness and helpfulness that we might have expected this from the Sandberg landowners too. It came in no small measure. Driaan Griesel was most enthusiastic and interested and also helped us with extracting our vehicle from the mud on the one occasion, and then jump-starting it after a flat battery on the second. Our imposition did not so much as touch his view of the day.

[Ed.] Bruce made another visit to Southwest Sandberg on 9 December 2012 and includes the following flower pictures. He makes this comment; personal correspondence 27 December 2012.

I am actually not sure at all about flowering time now. I used to be quite sure of being able to collect seed of pubescens mid-Nov. But I observed at Humansdorp that gordoniana peak flowering could be out by 6 weeks. In any case the plants can produce successive spikes so one can get delayed flowering and added to that energy in the first or the second flower set. I know mirabilis at MacGregor can flower from Nov. thru to March while at Montagu mirabilis can flower as late as April/May. Retusa and geraldii are quite happy to produce flowers in either Spring or Summer and Kobus observed that splendens did that too. Maculata can flower from Sept. thru to late Dec. And each population does its own thing.

.♦

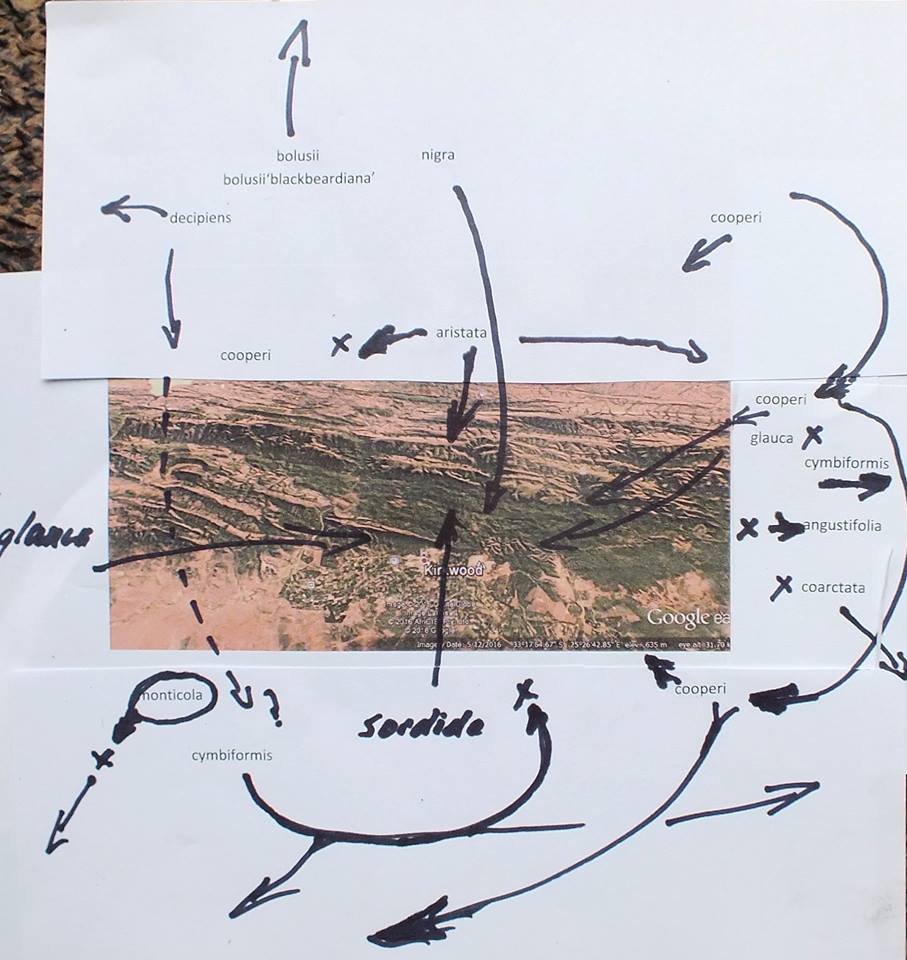

Genetic history – the place in Haworthia classification.

Preamble: Maybe the difficulties and strife in Haworthia classification is that we do not know what it is that taxonomists do. Taxonomy is the academic discipline of defining groups of biological organisms on the basis of shared characteristics and giving names to those groups. The scientists that do taxonomy are called taxonomists. The names taxonomists give to species don’t just tell us what they are called, but also tell us about how they are related to one another. In the following article Bruce Bayer shares his views that Haworthia taxonomy should be about more than identification and descriptions, rather the interpretation of the characters that reveal genetic relationships and evolutionary pathways. ~ Lawrence Loucka, 7 September 2012

Genetic history – the place in Haworthia classification.

By M. B. Bayer

This is a huge subject and I cannot by aptitude or knowledge attempt to cover it fully. However, it is so basic to plant classification and Latin naming that we all need to have some background understanding. The entire object of classification boils down to arranging living (and once living things) in a scheme that follows the theory of an evolution from simple life forms to the present array of creatures. This is because it is thought to be the logical way in which knowledge of the said creatures should be organised i.e. according to the way in which they traveled the creative way. All classification is simply a way of organising information so that one can generalise from the singular to the plural.

Whether one believes in such a progressive process or in a spontaneous divine creative event does not matter. All the evidence points to change of some kind and if we call it evolution does not alter anything. It is argued that there is in fact no direct proof that, say, man evolved from a primitive primate. That may well be so, but there are many fossil primates that are speculated to fill that gap. The case is that evolution is a scientific hypothesis and science does not, or cannot claim, that this is proven. A scientific hypothesis simple stands as a possibility or probability of something known. Such a hypothesis can only be proven untrue, and then it is replaced with a new hypothesis that stands as the accepted truth.

Whatever, the ultimate truth of the matter, classification in science is directed at reflecting how the different life forms are related to each other in respect of change? In the acceptance of evolution the process of change is the genetic history of the organisms and is referred to as the phylogeny. It is often depicted as a branching tree with the branches originating low on the trunk as ancient origin, to terminal branching for recent.

My experience with classification comes with education and qualification in entomology (insects). It so happens in insects (and higher animals) that there are many characters and structures that can be used to examine the process of change and modification that might go with evolution (change). The word “homology” is used. So, say, the wing of a bird is likened to the forelegs of a dog – they are said to be homologous structures. The change in structure from that of a segmented worm (eg. Onycophora) to say, a wasp, can be tracked through a whole range of insects. The head of a wasp is seen to be derived from 6 primitive body segments, the thorax from three, and the abdomen from several. There are muscles and nerve endings and sub-segments that are all evidence of these connections. In entomology, there was a stage when a qualification in insect classification required the student to also present a phylogenetic scheme to explain relationships relative to an origin. This all based on morphological characters, their homology and their interpretation as primitive or advanced. What is really odd is that too often a classification comes to deny the variability that a concept of selection and adaptation that evolution rests on, is denied.

In plants there is no luxury of musculature, or nervature or even detailed bone or segmented structure on which to base good homology. Botanists are therefore very hard-pressed to properly derive phylogenies or explain this genetic history. Nevertheless a very serious and honest effort is done to do this. The process of cladistics was derived from entomology (Hennig) and became the standard for the student in botanical classification. Students were required to evaluate characters on a basis of primitive and advanced, and construct cladograms that illustrated a hypothesized process of evolution. The advantages of the method over conventional decision making were that it is said to be an objective way of arriving at a conclusion rather than personal subjective decision making. With the complaints against my use of words and language, it is worth noting the remarks of a leading botanist who said that the methodology of cladistics was just the use of a new language that did nothing more than strain good-will. Agreed.

With the arrival of DNA sequencing, a whole new ball-game was created with each amino-acid base pair representing a character. So DNA sequencing has become the modern standard for the construction of phylogenies and genetic history – the phylograms. So much so that the article in Taxon 56:645-648, 2007 by A.B. van Wyk argues that the phylogram represents the process of phylogeny as the genetic history as opposed to the cladogram that attempts to construct the genetic history. I personally think that this is intellectual wizardry and the literature references in the Taxon article only expose the mystery that surrounds classification. It takes classification wholly out of the reach of any but a polymath. Basic to the whole issue is that scientists still have not reached any certainty about what a species is. The theory of evolution is not disproved. Van Wyk has said

Plant taxonomy, despite all its impressive achievements towards phylogenetic reconstruction, will then risk being denoted as yet another ivory tower science – a pursuit disconnected from the practical concerns and needs of everyday life, esoteric, over-specialized, its classifications of little practical use to the majority of end-users”.

It sounds very impressive, but I weep for the fuel that it adds to the fire of ignorance.

What truly appears to be the case to me is this. To construct a cladogram, the taxonomist needs to be very familiar with the plants and have a good understanding of the characters being used in the process; adjudging them according to some scale of advanced or primitive. The DNA sequencing method requires no knowledge of the plants at all and a phyllogram simply follows a statistical analysis of equivalence of the base pairs. What I see is DNA derived products that so far tell me no more than I already know about the genera, and nothing at all about the species other than some serious mismatches.

I argue for a species definition, not as some vague statement that species are things into which a genus can be divided, or simply a list of names under a Latin genus heading, or the zoological concept of closed breeding systems. My definition drawn from a lifetime of interest, observation and experience in things material as well as esoteric, is that the creation is a conscious one. This is not a new idea of mine. The conflict between religion and science is that the one maintains that creationism followed some sort of seven day event as in the book of Genesis. Whereas science (as we practice it today), has its origins in the quest for freedom from any such religious belief system. Whether creation began as a big bang, and complete or incomplete does not matter to me. We are faced with natural phenomena in the present that we can observe have changed and are changing. I do not think either the cladogram or the phylogram is anywhere near good enough as an answer, because they are two-dimensional diagrams that do not adequately portray the realities of time and space. Not only that, a three dimensional improved tree model will not show how fast things change within a time span. My model of the species tree is a fractal model that suggests species in a process of “chaotic” order. By the word fractal I mean the endless variation that seems to have no order. While I insist that the concept of a species of Haworthia must mean the same as the concept of a species of insect or frog, or bird or mammal, I do not mean that each species of Haworthia has the same branch clarity on any tree depicting relationships.

What I do not know is how fast populations might change in the process of genetic drift i.e. move off in a direction determined just by the local genetic content. Neither do I know how much nor how frequently interchanging of genetic material between populations occurs and how this is affected by distance between them. In the field there is a very distinct flow of difference (or similarity) with geographic spread. I have repeatedly found that with widely separated known populations, new populations between them are predictably intermediate. It does not seem entirely rational that there are not more random isolated individuals. My experience with hybrids is that they are very local to the mother plants while any populations tend to be very confined and local. What is odd is that hybrids may be found despite great differences in flowering times of the parent species.

The reality in Haworthia, however we define species, is that there are populations that are neither one taxon nor another. If the classification were to present a basic requirement that ALL populations known and unknown must fit the model, then definitely we have to consider that there are considerably less species than other writers are prepared to consider. One can continue building a classification from the top in which each new population is simply described as something new and given a Latin binomial. This process was suited to the origins of botanical exploration as well as nomenclature. It does make it a lot easier for collectors and the exciting process of always novelties for the collector. Alternatively one can decide that classification is by this stage a fully predictive one and one that must primarily suit the requirements of botany. If only botanical classification was more professionally and rationally based. Sampling is very extensive and a classification based on the known, is predictive. Personally I am very comfortable that I have achieved this in large measure – not entirely, but close enough and a lot closer than some critics will concede. With all that said and done, it is just a sad fact that formal classification is too often undertaken by people who have a need. That need may satisfy them within the limits of their personal experience and knowledge, with an uncomfortable disregard for the depth of knowledge elsewhere.

Reference: Readers can refer to the article in Haworthia Update Vol.2:149 (2006) “Nectar sugars in the Alooid minor genera and a need for another model”.

♦

Haworthia mutica (groenewaldii) and its twisted leaves.

In this article Bruce Bayer responds to the notion that apparent leaf twist arrangement is a defining characteristic and further explains his disagreement in recognizing the Buffeljags plants as a new species. (Also see Haworthia flowers – some comments as a character source, Volume 7, Chapter 4:- What is typical Haworthia mutica?, and Volume 7, Chapter 2:- Further exploration in Haworthia. Further to finale.)

The species definition Bayer uses is that populations are fractal and DNA is governed by mathematical non-linearity. What does that mean? We have space with two dimensions latitude and longitude, and we have time with two dimensions – calendar time, and the speed (instability) of the arrangement of the DNA base pairs. At any moment in linear calendar time there will be an arrangement of the DNA depending on the stability of the DNA. At one time there will be a clear set of ‘species’ and at another time a different set as the mix of characteristics continually change within and between the populations. ~ Lawrence Loucka

Haworthia mutica (groenewaldii) and its twisted leaves.

By M.B. Bayer

There is some argument about the status of this population of plants at Buffeljags. I have explained my opinion of it based on a species definition that I use. I also have reported on three other populations a short way away at Rotterdam. Furthermore I have discussed the flowers at length in a flower report. These are all available free on Haworthiaupdates.org. Gerhard Marx does not agree. The disagreement first has its roots in what constitutes a species and Marx stays with the standard view that characters are what define species. I opt for the view that species are systems related to geographic distribution and to all the elements that drive vegetation and change (evolution + equals change from some unknown initial condition). I think these patterns of change and difference are fractal i.e. detailed pattern repeating itself. Perhaps it would be more correct to say that the organization of pattern is according to a mathematical function which is non-linear. This means that the end product has many different outcomes. But this is complexity just of argument that none of us can deal with.

What comes into the geographic nature of species is also the nature of habitat. What happens is that we have a set of apparent species in Haworthia with a known distribution range. These species are primarily H. retusa and H. mirabilis. There is clear evidence that H. pygmaea and H. mutica emerge from a milieu of populations of those two and that H. floribunda is also involved. Buffeljags is geographically central to this arrangement and the habitat (wrongly described in the description of H. groenewaldii) is very unlike those where the named species generally occur. It is thus no surprise that the plants appear different. The Buffeljags population and its habitat also differ to a small degree from the west side of the river, but both are essentially geologically fairly recent river alluvial deposit.

Marx is insistent that the plants at Buffeljags are so different as to be a discrete species and I disagree. My disagreement is based on my experience of characters in plants. In Haworthia I think these are few and obscure. Thus it is almost impossible to delineate or circumscribe a species by characters and no one has succeeded in producing an identification key that can work. All the differences of opinion and argumentation about names come down to this issue of a species definition and the characters available to recognize them.

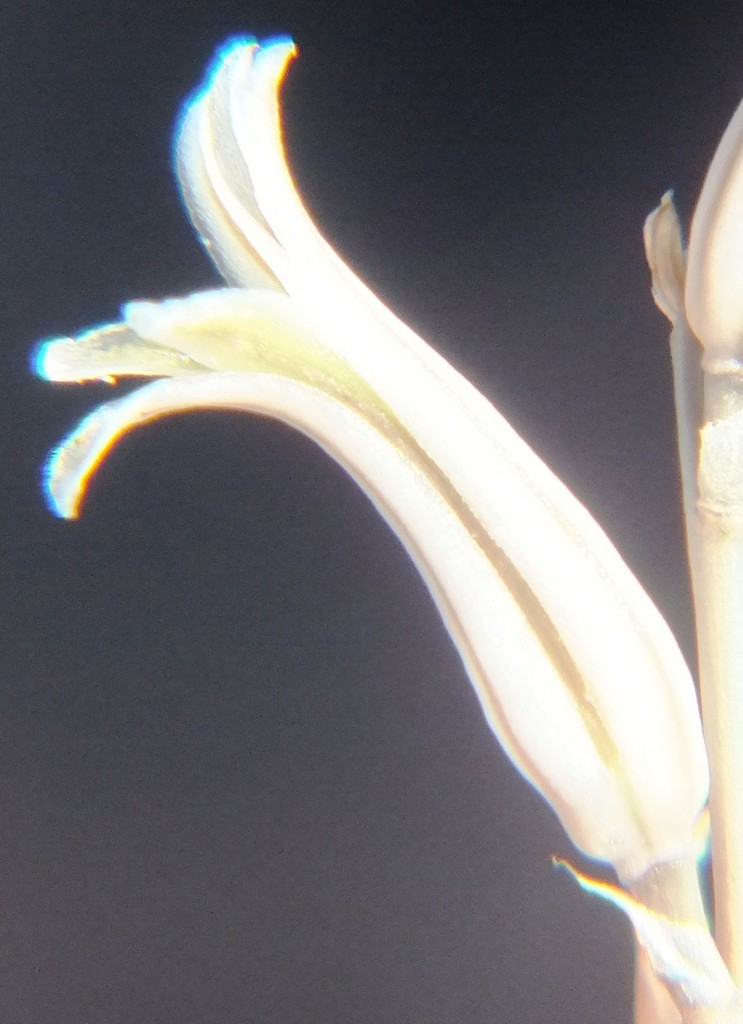

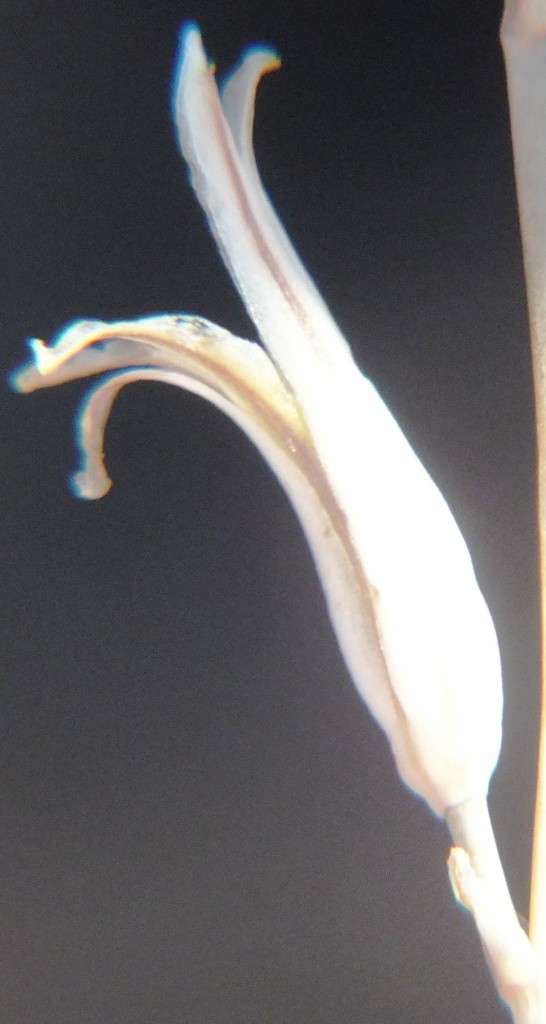

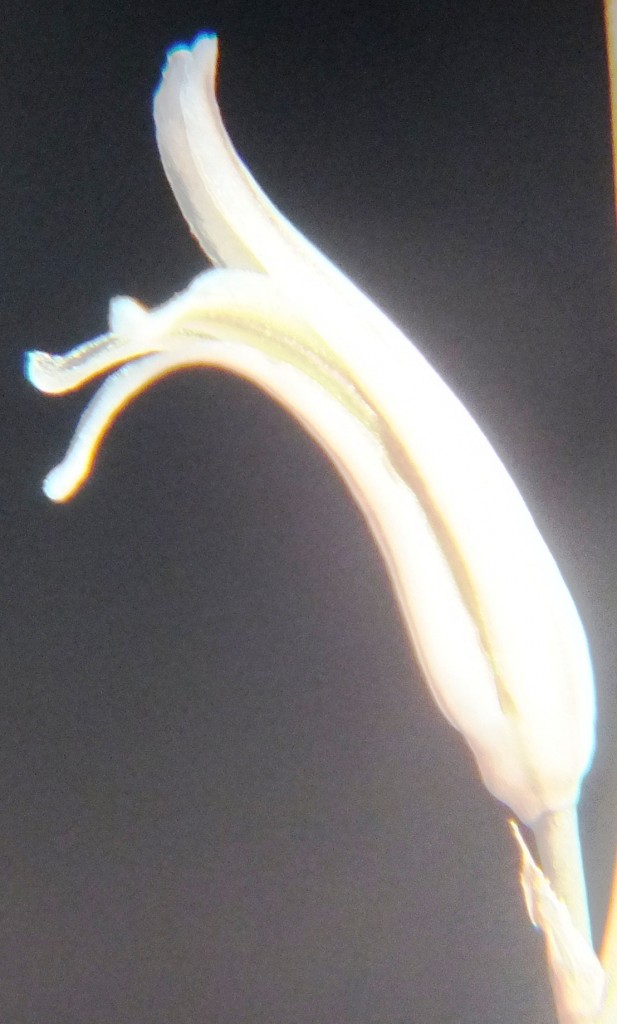

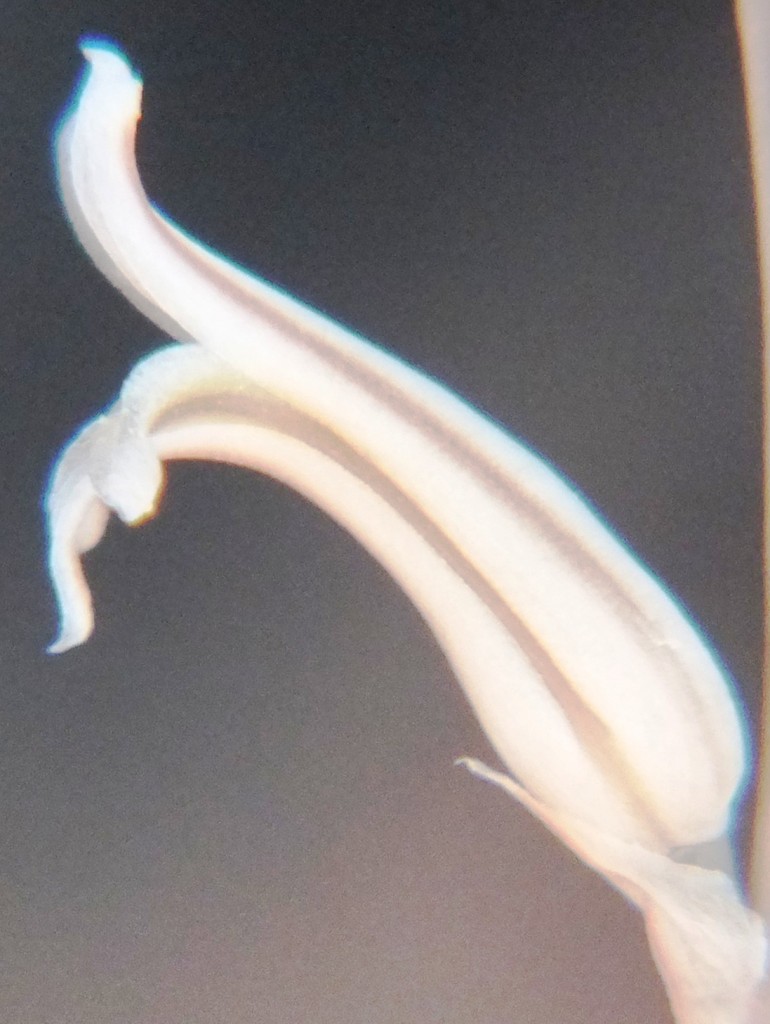

The essential points made for H. groenewaldii as a species is the shiny leaf surface and the flowering time. H. mutica does flower four months earlier – agreed. But H. marginata in the same close area also flowers similarly out of synchronicity with H. marginata elsewhere, as H. minima was also observed to do. In elaborating differences for H. groenewaldii, Marx offered the facts that the plants had fish-tail buds and that H. mutica did not. Very soon after he stated that he did not actually know what the case was in H. mutica.

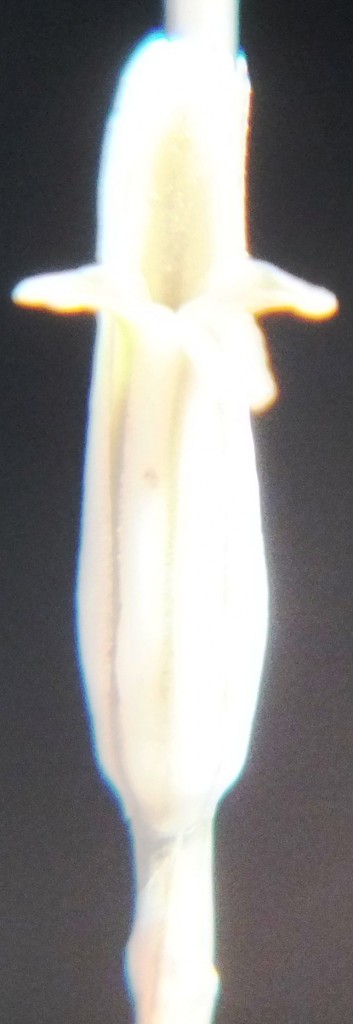

Fig. 1 to 9, MBB7801 Haworthia mutica (groenewaldii), Buffeljags.

In addition he maintained that the leaves in H. groenewaldii were different as follows…”In terms of the angled newer leaves of H. groenewaldii, have a look at the plants again and you’ll see the young leaves are consistently twisted sideways. A spiraling effect. This never shows up in H. mutica”. I find this statement very odd because such a structural difference would come down to a difference on the level of genus or even family. So I looked at the plants I have in my possession and provide illustrations here to demonstrate no significant deviation in respect of twisting. I have even included a picture of a mature plant (fig. 10) of H. mirabilis to show the same “character”. The spiralling effect is universal in the aloids and is even visible in those species with distichous leaves. In the retusoids, where H. mutica belongs, the leaves have been said to be 5-farious. More usually it is possible to see them as trifarious. In young seedlings the leaves are bifarious as the very basic spiral effect comes into play.

I do not think this is a character one can use to distinguish a species at all. There are many cases where it is fairly possible to characterize populations by a wide range of so-called characters. My opinion is that generally in the many species (by my definition) of Haworthia this can virtually only be done at individual plant level. The Buffeljags and Rotterdam populations are simply the western counterparts of populations around Albertinia (eg H. mirabilis ‘splendens’, H. pygmaea ‘fusca’, H. pygmaea ‘esterhuizenii’) that emanate from the relationship of the prime species that I named above.

♦

Comprehension and significance

My writing has been described in all kinds of terms, hermetic and pretentious being two of the adjectives used. Recently Kris Tamayo also suggested that he had trouble understanding what I wrote or write. The fact is that writing and expressing yourself is difficult. But the first place is to be clear about what you want to say.

Writing is a means of communication and it really only should start when you are clear about what you think and what you want to say. Then it requires that the listener is clear about what one wants to hear and has the common cultural heritage that permits communication and understanding to occur?

In writing and talking about plants I personally get very frustrated by the technical problems of definition and knowledge that mess up communication completely. This is one of the obstacles in classification where there is no species definition and we do not actually know what species are. There are a lot of other obstacles. Recently someone wrote and implied that there were a lot of significant differences among Haworthia that could be used to arrive at a better classification (than any already available). The point I would make is that this person has his own idiosyncratic view of what significance means. This is not strange at all because a prominent scientist was once applying the statistical measure of standard deviation to two and three measured samples. That measure probably cannot be used until many more measurements are made. What is taken to be significant may be quite irrelevant to the actual question of whether there are more or less species. This is why amateurs and collectors should keep clear of classification. The professionals already have too many problems.

The characters we use to make identifications are important in that they may be of the yes and no kind i.e. present or absent, or they may be graded from vague to prominent. So it is very easy to go to one end of the scale and take only the prominent or what happens to strike your eye. This is exactly what happens. Unless followers and interested parties realize the impact this sort of decision making affects what they may want to know and understand, there can never be any harmony and peace in the classification process.

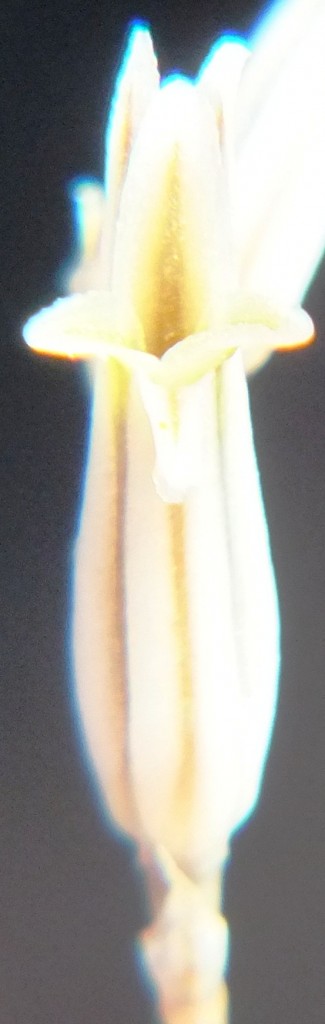

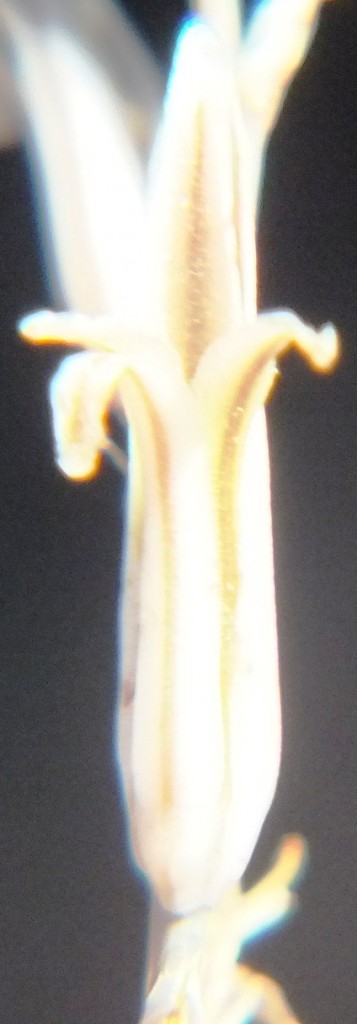

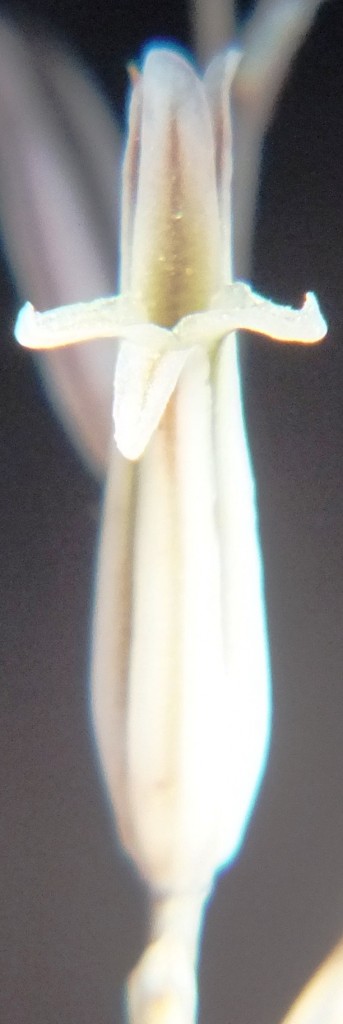

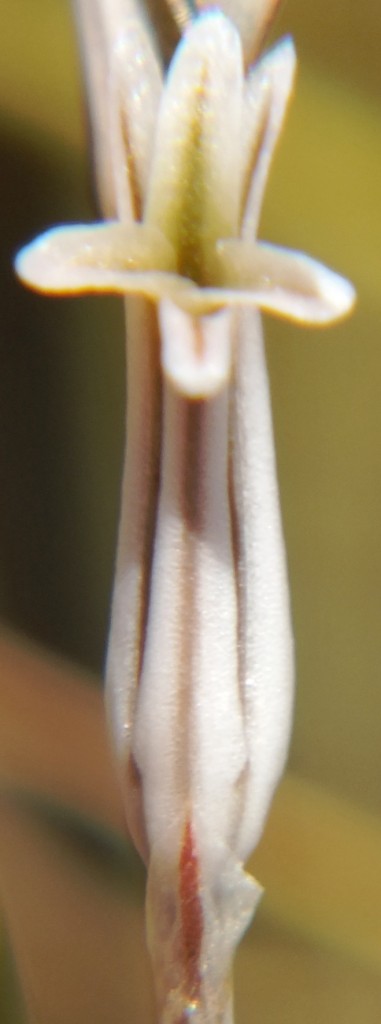

Look at these flowers and see what you can glean from them…

These just happen to be the only three flowers I have of a few plants of Haworthia herbacea from recent sampling. They are shown here in correct proportion to one another with the third being 18mm across at widest spread of the two upper outer petals. So we have two things we can call characters i.e. size and colour that we could say in respect of this simple sample, that they are significantly different. No matter how many times or how we measured these two things, this fact would stay the same. The plants happen to be from two populations and we can then ask if this is true for those populations. I did ask such a question of both H. herbacea and H. reticulata, and ended up by learning that I needed a sample of about 200 flowers to arrive at a statistically true answer at a probability of 95%. The thing is that I could go a little further south and sample another population and get a really pink flower with a spread of 25mm or more that would nearly double the spread of my measurements.

There are several incidentals here. One is the delineation of the mouth into the tube of the flower. Why is it so clear in the third picture? The second is that the first flower has not opened as flat across the face as the other two despite being at the same expected state in respect of time from opening. The third is that the name “subregularis” was used in this genre of flowers because the petals are so equally spread; perhaps less-so in the middle picture. Still a fourth curiosity is that in the southwestern species with the more extreme biarcuate bud with the fish-tail tip, is how the tips of the upper outer petals are “replicate” – i.e. the margins tend to fold together. In the Worcester/Robertson Karoo particularly H. herbacea and H. reticulata have the “regular” flower shape. But in H. mirabilis in this area, the upper outer petals may be held in a plane directly behind the inner outer petal and do not spread at all. There the bud tip is still fish-tail and the upper outer petal tips very replicate. ♦

MBB6694 Kanetvlei, Hex River Valley as a variant of Haworthia nortieri.

In Haworthia Update Vol. 9 dealing with H. maculata, I again draw attention to several populations that are problematic in an area very difficult to explore. The populations are MBB7865 at Keurkloof southeast of DeDoorns, EA1441 at the Hex River Pass, an unrecorded population south of Sandhills (about 3km east of Kanetvlei) reported by Ernst van Jaarsveld. In addition there are two populations apparently of H. arachnoidea at Tunnel Station east of Osplaas.

The illustrations that accompany this article are:

- MBB6694 Vreesniet, Kanetvlei.

- EA1441 Hex River Pass, east DeDoorns.

- MBB7865 ex E. Van Jaarsveld, Keurkloof, DeDoorns.

This population MBB6694 is at Kanetvlei southeast of Sandhills, and I originally ascribed it to H. arachnoidea but this is not correct. To this I can add unexamined populations reported by P.V. Bruyns deep in the Langeberg at Keerom Dam and another of Ted Oliver in the mountains north of Nuy. MBB6694 is only 200-300m north of MBB7994 also in sandstone. The sandstone strata are by no means all the same and one can even find shale bands in what is essentially a sandstone formation. H. maculata flowers late winter to early spring and these other populations in early summer.

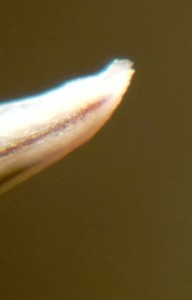

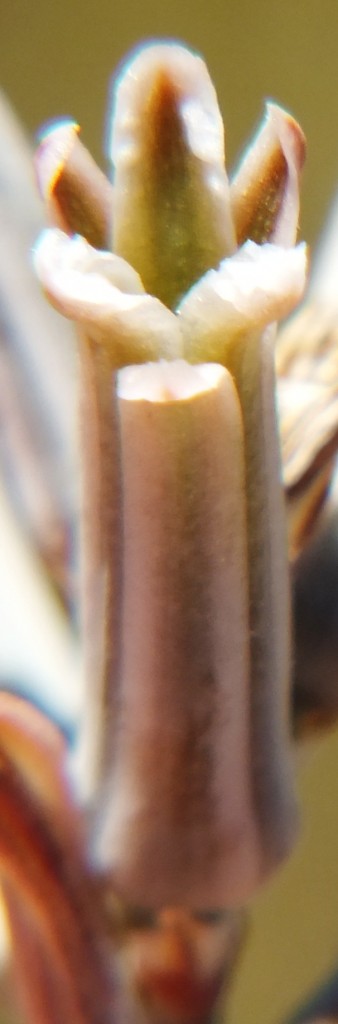

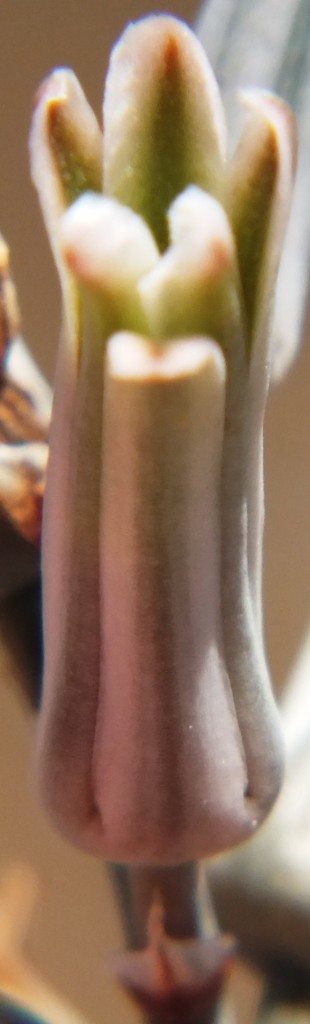

I have not examined the flowers in any number and remain doubtful that this information will clarify any deductions that can be drawn from the vegetative characters or the geographic positions of the populations. It appears to me that consideration must be given to a relationship with H. nortieri that in my assessment occurs from the far northwest to as far east as Prince Albert, i.e. H. nortieri (devriesii). What I have seen of the flower, and shown now is that it definitely does not belong in the context of the Southern Cape species where the bud-tips tend to be “fish-tailed”. The inflorescence are slender and few flowered.

There is some criticism of my emphasis on geographical distribution as a key indicator of species. It was even said, as though I would have denied the fact, that I could not identify plants unless I knew where they came from. There is an incredible amount of both ignorance and the obtuse behind these statements. One critic feels that I have ignored detail and even ignored flower characters in the development of my opinions. This same critic claims a high degree of agreement with me (80%) based apparently on the view that so much of my classification is correct (meets with his approval), and presumably that the 20 percent that he contributes to the system makes it 100% correct. This is wholly wrong. This critic is simply unable to bridge the historical chasm between his introduction to, or knowledge of, Haworthia and mine. He simply does not recognise the shift in method and why I switched from a “character-based” approach to a phytogeographic one. It is really very simple in that the character based system as used from the very beginning of classification, has not produced a solution to the identification and classification of Haworthia. It all rests on a very weak and shaky definition of species determined by breeding barriers and consequently that morphological differences necessarily exist. My approach was to show that breeding barriers (at least in plants) could be integral to species and that morphological differences could equally be nothing but variation within species. Therefore I arrived at a definition of species from the view that they were phenomena spread in space and changing with time. This is just a fundamental of plant species as they constitute the vegetation and the floras of the world. Virtually the first question following “What is that?”, is “where does it come from?”.

Why 6694 is so interesting is precisely because it occurs in an area which is so poorly known and represented in our knowledge of Haworthia. The reality in the subgenus Haworthia is that there are several areas of great species richness and there is real pattern in the distribution of the various elements as they are listed in the 80% agreement area. The 20% disagreement zone concerns truly trivial opinion and unsubstantiated statements, and almost ignores the real reasons for disagreement at all. The real reasons are the realities that superficial morphological difference does not mean species and I have posted a vast amount of material that demonstrates that. I have shown repeatedly that differences in single characters in what can be rationally said to be the same species, can be greater than between different species.

In the case of 6694 I did not pick any particular character to identify the plants as H. arachnoidea from probably as far back as 1975 and I can find no earlier record of this location. I do recall a specimen in the Compton herbarium made by W.F.Barker that I mentally allied with H. arachnoidea but it is not cited as such in my revision. The identification was based on little else other than the spiny-ness of the plants and the fact that the nearest known locality for that species was a very new one of mine a few kilometres to the southwest. At the time, H. nortieri was barely known and this was from far to the northwest at Clanwilliam. Since then H. nortieri has become much better known although still some distance north of Ceres, and with its globose-flowered variants at Laingsburg and eastwards. H. arachnoidea remains remarkably unknown from the Cedarberg and Koue Bokkeveld mountains but does appear in the upper Hex River Valley. Here it is odd that the leaves tend to have the translucent dots that one would expect to characterise H. nortieri. But otherwise the leaf coloration is the much darker green that is associated with H. arachnoidea. A twist is that at Kunje, southeast of Citrusdal, H. nortieri does have very dark green leaves and there is no doubt that confusion with H. arachnoidea is inevitable. I have very little to offer in this regard because this degree and level of confusion or doubt is intrinsic to the genus anyway.

Why I now decide to relate this Kanetvlei population to H. nortieri is not to be construed as a decision now to call white what previously was clearly and definitely black. It is taking all my knowledge and experience to suggest simply that this is a better reflection of the situation where there is not enough hard data to determine identity at a higher level of certainty than about 50%. What I do suggest that there are many situations in Haworthia as the case with H. maculata and H. pubescens only recently exposed. In this case the two very different elements can be very confidently be said to be the same in respect of distribution and linking populations AND characters. Throughout, particularly the subgenus Haworthia, we have situations of continuity and spatial (geographic trend) and nearly all my many publications deal with exactly this reality. What it suggests is that my critic should come to consider if he has some other motive between punting points of difference that prevent him from finding points of agreement, besides those that rest coldly on logic.

1. MBB6694 Vreesniet, Kanetvlei.

Flower profiles.

Flower faces.

Flower buds.

2. EA1441 Hex River Pass, east DeDoorns.

3. MBB7865 ex E. Van Jaarsveld, Keurkloof, DeDoorns.

♦

Haworthia minima and pumila flowers

This H. pumila flower is apparently persistently regarded by botanists as actinomorphic (star-shaped, radially symmetrical) – as though zygomorphy (yoke shaped, bilateral, asymmetrical) in the aloids is an uncommon condition!

Radial symmetry means the flower can be divided into 3 or more identical sectors which are related to each other by rotation about the centre of the flower. Typically, each sector might contain one tepal or one petal and one sepal and so on. It may or may not be possible to divide the flower into symmetrical halves by the same number of longitudinal planes passing through the axis. Zygomorthic flowers can be divided by only a single plane into two mirror-image halves, much like a yoke or a person’s face.

If you see the way the inner upper petal overlaps BOTH the two lower inner petals, you recognise that there can not be actinomorphy in aloid flowers.

Haworthia pumila

Haworthia minima

♦

MBB7989 Haworthia pumila, Lemoenpoort

Kobus drew my attention to a glabrous plant of Haworthia pumila while he was photographing this species at Lemoenpoort. The plants here have a missing chromosome and tend to have a purplish colour. I have seen smooth non-tubercled leaves elsewhere. But do check out that one plant – if you look carefully you can see the leaves are in 8 nearly vertical tiers. Proper botanists recently, for Taxon, described the arrangement of leaves like this in only two tiers (e.g. H. truncata) as “distichous insertion”. This is weird. Are the leaves in this plant of H. pumila “octichous”? Is H. viscosa “tristichous”. No, the leaves in the aloids are alternately and spirally inserted.

Flower profiles

Flower faces

♦

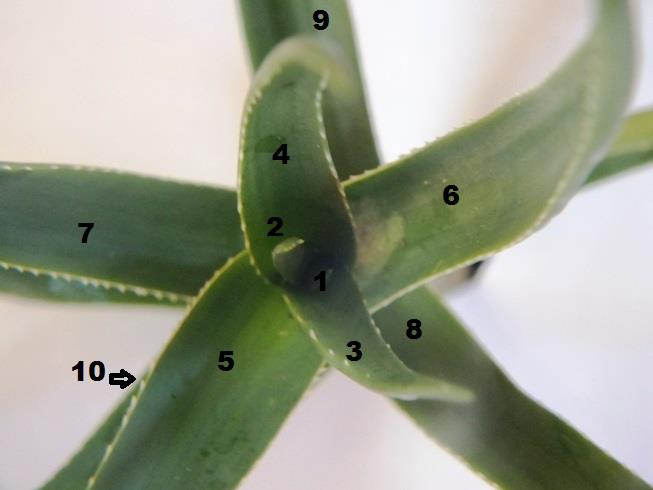

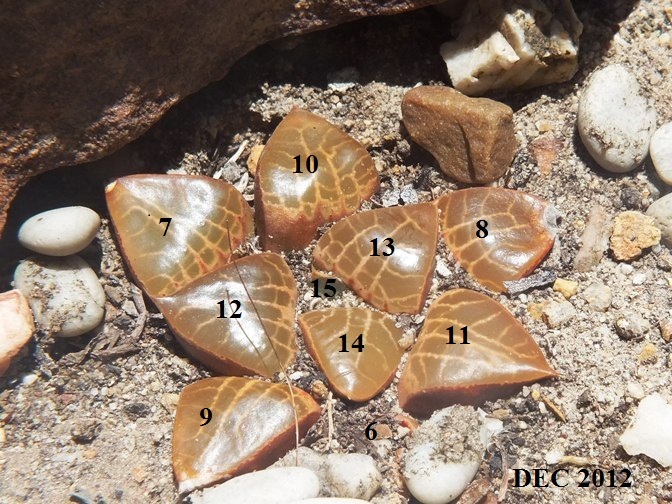

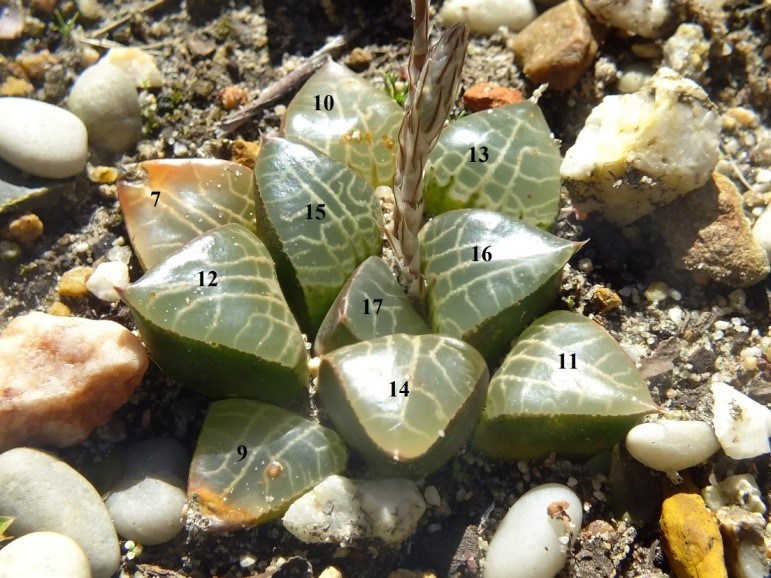

Leaf arrangement in Aloe striatula

Herewith is an image of the leaf arrangement in Aloe striatula. I have numbered the leaves in inverse order to show that the leaves are as much distichious as trifarious i.e in two rows or three. The primary set is 1 through 10, the distichous set is 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. The trifarious set is 1, 4, 7, 10; 2, 5, 8 and 3, 6, 9. I have also added a picture of the leaf insertion – here it is entire and there is a leaf sheath around the stem – the actual point of insertion is at the pointer although the “veins” continue through that point to the stem itself. In this species the next leaf is inserted just below the opening of the previous sheath. Despite the leaves being alternate, they are spirally arranged. In Aloe broomii the leaf insertion is continuous and you can peel all the leaves off the stem in one piece. In most Haworthia the leaves are imbricate (overlapping alternately) but always in a spiral sequence. H. wittebergensis has leaves that have entire insertion and by memory the same is true for H. blackburniae and maybe for H. viscosa. ♦

Just what do we do with names for Haworthia?

Previously published in BCSJl (Cactus World) 30.4:211(2012)

M B Bayer

Taxonomy always provokes differing views, and Haworthia in particular has been subject to years of vacillation. The author has long been a campaigner against the haphazard proliferation of new names for every new, morphologically different population or variant. He questions the vagueness of a conventional species concept and pleads for a more reason-based, logical and sensible, communal approach to understanding and classifying Haworthia species. He hopes in this article to convey a message which is relevant to whatever genera of plants you grow. Photography by the author.

In Haworthia, professional botanists have struggled with and avoided the group because it is so infused with amateurs whose interest in the genus far outweighs any knowledge of botany. So classification of Haworthia has muddled on with scant regard for the discipline of botany as a science. Whether that has changed, is not for me to say. I have personally been gathering information on distribution and variation for over 50 years and have very seriously tried to keep that in the context of the science I was trained in and present it in a manner that botanists can follow and hopefully accept.

What has developed is that academic and professional botanists have been working with the tools of molecular biology and the results of five independent studies have all pointed towards the same conclusion, which is that the species of Haworthia are elusive, and the related genera are also not adequately distinguishable in the DNA data. The best solution they can offer is to merge the genera back into a single genus, namely Aloe. My personal reaction is that this is not a new idea and also Gordon Rowley pointed this out as far back as the 1970’s. I have also said that the subgenus Haworthia does not sit comfortably with the other two subgenera. Had I been a true taxonomist I would have implemented that by separating Haworthia into three separate genera and that is what I really would like to see. But the reality is that this does not solve the other problems that exist regarding Astroloba, Chortolirion, Poellnitzia, Chamaealoe, Leptaloe, Lomatophyllum, and the small Madagascan aloes. True botany alone can resolve the current and a new classification (still in manuscript form) has been proposed by a group of scientists that will really ‘rock the boat’ as far as collectors are concerned.

In Haworthiad (2012:4), I wrote about Haworthia mirabilis ‘submagnifica’. (Ed. note: The name in inverted commas, according to the author’s system indicates a variant name rather than a formal conventional variety, subspecies or form. It is his contention that there is no species definition and thus formal names have a large element of uncertainty. Another option is to drop the use of any rank denotation at all). It is one of the first populations linked to von Poellnitz’ H. magnifica long before so much was learned about distribution and variation. I used the prefix “sub” because this means “somewhat”, “almost”, “slightly”, “partially”, and possibly a few other words that mean… it is, but it is not. The population concerned is Komserante (Figs 1-2) and this particular population has acquired the name H. vernalis (Figs. 3-4). But I think we need to start from scratch and drop all the ‘baggage’ of the years. I personally have learned so much since I wrote my revision in 1996 that I know it is not possible to properly backtrack and retrace the passage forward by the use of Latin names. Interfertility is the basis of the system we use to identify and describe species and my field experience was already proving that this cannot possibly apply in the way in which Haworthia has been, or is to be, classified.

It is quite evident that H. retusa and H. mirabilis, both of which I accept in a very much broader context, do hybridise and there are populations that fit between. But first let me just explain that I regard H. retusa now to include H. turgida and all the variants of that species (nomenclatural priority obviated the use of the name turgida to cover the greater body of populations for this species). In the same way I regard H. maraisii, H. magnifica, and H. heidelbergensis and whatever variants were attached to those, as H. mirabilis. There are thus two species. My further observation is that H. pygmaea and H. mutica are segregates from the common gene pool of H. retusa and H. mirabilis. The Komserante population is the one in which that same gene pool is re-combining (Figs. 5-10). I am not in the least sure of all the intricacies but it seems to me that it is actually the group of populations that I recognize as H. retusa var. nigra that is pivotal in the relationship of all these species that I recognize. In this we discuss populations using names as prescribed by convention. This convention caters for chronology and authorship and not for evolutionary pathways. Both the names “retusa” and “turgida” precede the name “nigra”, but the populations that I now assign to H. retusa ‘nigra’ may better fit the concept of evolutionary origin.

The picture is complicated by the role of H. floribunda. This also hybridizes with both H. mirabilis and H. retusa as odd hybrids as well as at a population level. Just what are we to do? History has demonstrated all too well that a bevy of ill-assorted interested parties trying to impose a botanical classification is going to produce nothing but conflict and confusion. This has been going on now since the time that Smith, Von Poellnitz and Resende were simultaneously describing new species. How are we going to turn around and arrive at the understanding and stability of names that we seek?

In the past I have been extremely reluctant to make the following suggestion, and even now am a bit hesitant. What we need to do is turn to people who are employed to do this work. Herbaria and herbarium botanists are tasked and entrusted to classify and name plants. Perhaps it testifies to the complexity of the subject, or just its enormity, that these botanists have too often needed to defer to amateurs who have the interest, energy and enthusiasm and commitment to acquire field knowledge that a professional could never get the time or funds to do. The unfortunate part is that sometimes amateurs may not be able to relate their knowledge adequately to academic botany.

So what is the solution? It is that the community leaders assume the responsibility for the establishment of a system of classification that is meaningful to the community they serve. By community, I mean initially the botanists who should be providing us with scientifically sound classifications, then editors who are familiar with what botanists do, next are the Societies with their memberships, and also opinion formers in those groups. Finally included are the reviewers and commentators who lead opinion in one direction or another. It is surely not that difficult to sit down together to discuss and arrive at a set of guidelines by which a decision can be reached as to what (not whose) system to accept. A solution does not belong to anyone. Latin names are assumed to refer to an entity called a “species”. Botany has indeed been very lax and remiss in not providing a definition and this is the prime reason why amateurs have had so much freedom in generating Latin names for the most frivolous reasons. Botanists themselves have often not been far behind.

I think it is time to change all this and must excuse myself from any decision making body or process because I have a vested interest in respect of all the words I have written on the subject.

- Haworthia revisited. Umdaus Press, Hatfield. (1999)

- Plants in my collection 7: H. mirabilis ‘magnifica’. Haworthiad 26(1): 4-5 (2012)

♦

Nomenclator (2013)

The Haworthia nomenclator: a list of accepted species with some guidelines for infraspecific names

M.B. Bayer* and J.C. Manning**

*PO Box 960, Kuilsriver 7579, South Africa

**South African National Biodiversity Institute, P/Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa

7 October 2012

(revised 1 February 2013)

With the impending revision of the IOS Succulent Lexicon and a growing awareness that the current classification of the genus Haworthia is unnatural, the time is ripe to propose a list of species names that I (MB) consider worthy of recognition. This list is essentially the same as that published recently in Haworthia Update 7(4): 30–40 (2012), in which we formally published numerous new combinations and new synonyms. There are two changes from that list implemented here. New information prompts us to recognise H. marxii as a species distinct from H. emelyae, and we transfer var. livida from H. pubescens to H. maculata also on the basis of new information.

My considered opinion is that there are at most about 60 species in Haworthia and that a better and more critical treatment would reduce this still more. This contrasts markedly with Breuer (2010), who lists 368 ‘accepted’ species and reports the even more startling claim that Hayashi recognises 550! Some of this increase is due to the tendency for these authors to treat my varietal names as full species but they have also described many new species de novo. I am unable to accept all of their proposed taxa in the context of my extensive field knowledge of the genus and my practical experience of patterns of variation among wild populations.

Species concepts in the genus have always been idiosyncratic, driven primarily by a propensity to recognize variation over similarity and fostered by a general ignorance of the extent of intra-population variability in the wild. The recent almost exponential proliferation of names has succeeded in surrounded the genus with a thicket of nomenclatural twigs that is almost impossible to penetrate and which obscures rather than illuminates any real understanding of the genus. The very appeal of the genus is its almost infinite capacity to vary, and it is a tragedy that they are no longer appreciated for their individuality but are instead pushed into or pulled out of taxonomic boxes almost willynilly. It is very difficult not to suspect the motivation behind some of this bedlam.

While we in no way wish to proscribe anybody from expressing their opinions, we issue an urgent plea for restraint. The nomenclatural flood that has all but submerged the genus will only be exacerbated by floating additional formal names and combinations on the turbulent waters. In fact, we go so far as to recommend a moratorium on the publication of any new taxa in the genus that are proposed without an extensive survey of relevant variation patterns in the wild. Scientific journals reduce the chances that inadequately researched papers will see the light of day by sending all submissions to competent referees for comment and evaluation. Popular journals that transgress into the scientific arena by accepting descriptions of new taxa should do the same and the responsibility for this lies firmly with the editors.

Every scientific name that enters currency has to be accounted for by botanists in their lists and publications. To remove them from circulation requires a separate, formal act for each and every name. Dealing with the many dubious names in Haworthia is taxing task that can be ill afforded. Numerous invalidly published or illegitimate names have also entered circulation through non-adherence to the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, which aims to regulate scientific names. This adds to the confusion and to the work.

What in fact is the primary purpose of these scientific names? Among botanical circles, species names carry a great deal of weight. In most instances they imply that individuals that share a name also share a common ancestry and can interbreed to produce viable seeds. Species with different names will not. Is this philosophy applied in Haworthia? The process of recognising species in botanical circles is generally top-down, with genera being first split into component species and the species then into subspecies or varieties acording to the particular patterns of variation shown by the constituent populations. This does not seem to apply in Haworthia. Here the process is largely bottom-up, with individuals or populations being given names and then shuffled into or among species. This is patently absurd.

In general terms, botanical names largely reflect similarities whereas horticultural names highlight differences. The two systems are thus not always congruent and little is to be served by confusing them. We therefore recommend that growers exploit the advantages of an informal system of nomeclature that will give them unlimited flexibility without clogging up the formal nomenclature any further. We also urge the Editors of popular journals to encourage the use of this system among their contributers. The great advantage of such an informal and non-ranked system is that it removes the hierarchical constraints that are inherent in the Linnaean system and that have already created problems with the placement of varieties and forms of Haworthia.

It could not be easier to implement and use: instead of worrying about the taxonomic level at which the variant is to be recognized (is it a subspecies, or a variety, or a form) the name appears in inverted commas without any indication of its rank. Such informal names can also be moved between species without any formal changes that are otherwise necessary. They are likely to be more descriptive and meaningful than a bare Latinised trivial epithet. As an example, should Mr Smith consider that the form of H. mirabilis var. sublineata from south of Bredasdorp with paler, attenuate leaves deserves special recognition, then he might usefully refer to those plants under the informal name H. mirabilis ‘Bredasdorp Pale’ Smith 2015. A typical illustration should be designated to fix the application of the name. Transferring of the variant to another species should follow the Zoological Code in carrying over the first author only (now in brackets) and not the transferring author as well. Thus: H. mirabilis ‘Bredasdorp Pale’ (Smith 2015). We are most grateful to Harry Mays, Editor of the Haworthia Update for his assistance and advice on this aspect.

THE LIST: All taxa that we accept are indicated in bold.Taxa that are not accepted at any rank are included as synonyms. Where possible we formally synonomise such names that have not yet been formally synonomised but many others (indicated with an asterisk *) do not appear in the International Plant Names Index (www.ipni.org) as of 20 January 2012 and are thus evidently unpublished or manuscript name. The publication of such names in the literature is irresponsible. Names that are separated by a full stop (.) are based on different types (heterotypic or taxonomic synonyms) whereas those separated by a colon (:) are based on the same type (homotypic or nomenclatural synonyms).

Haworthia Duval Pl. Succ. Horto. Alenc.: 7pp (1809). Baker in Jl. S. Afr. Bot. 18: 197(1880). Baker in Fl. cap. 6: 332 (1896). Berger in Das. Pfl. 4: 74 (1908). Bayer, New Haworthia Handb. (1982). Scott, The genus Haworthia (1985). Type species: H. arachnoidea (L.) Duval. [Typification largely by Breuer & Metzing in Taxon (1996)].

= Catevala Medik. (1786). Apicra Willd. (1811).

± 60 species, very variable and complex. The taxonomy of the genus is still unresolved. Species concepts used here largely follow Bayer’s (1976, 1982, 1997) treatments and are based on geographical distribution and co-occurrence.

NOTE: Recent phylogenetic analyses of nuclear and plastid DNA sequence data supports the view that the three subgenera comprise quite distinct lineages not immediately related to one another. They are thus as distinct as some of the other smaller genera and should thus logically be treated as separate genera. A more useful option is probably to include all of the alooid genera within Aloe.

Key to the subgenera

1. Flowers triangular or rounded-triangular at base; tube obclavate-curved; outer tepals free; style upcurved; seeds irregularly angled . . . subg. Haworthia

2. Flowers hexangular at base, gradually narrowing to junction with pedicel (substipitate); tube obcapitate-curved; outer tepals partly fused to inner; style straight; seeds irregularly angled . . . subg. Hexangulares

3. Flowers rounded at base and abruptly joined to pedicel (non-stipitate); petals partly fused; tube obcapitate-straight; style straight; seeds flattish . . . subg. Robustipedunculatae

I. Subgenus Haworthia. Type species: as for genus. ± 41 spp.

H. angustifolia Haw. in Philos. Mag. J. 66: 283 (1825). Neotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Grahamstown to Alicedale, Bruyns 1653 (NBG).

= Aloe stenophylla Schult. & Schult.f. (1829). H. albanensis Shonl. (1912). H. angustifolia var. grandis Smith (1943).

H. angustifolia var. angustifolia

H. angustifolia var. altissima Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 26 (1999): H. altissima (Bayer) M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 3: 13 (2000). Type: Riebeek East to Carlisle Bridge, Smith 5220 (NBG).

H. angustifolia var. baylissii (Scott) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 27 (1999): H. baylissii Scott (1968). Type: Oudekraal, Zuurberg, Bayliss sub Scott 796 (PRE).

H. angustifolia var. paucifolia Smith in Jl. S. Afr. Bot. 14: 48 (1948): H. paucifolia (Smith) M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 22: 11 (2010). Type: Frazers Camp, Smith 6819 (NBG).

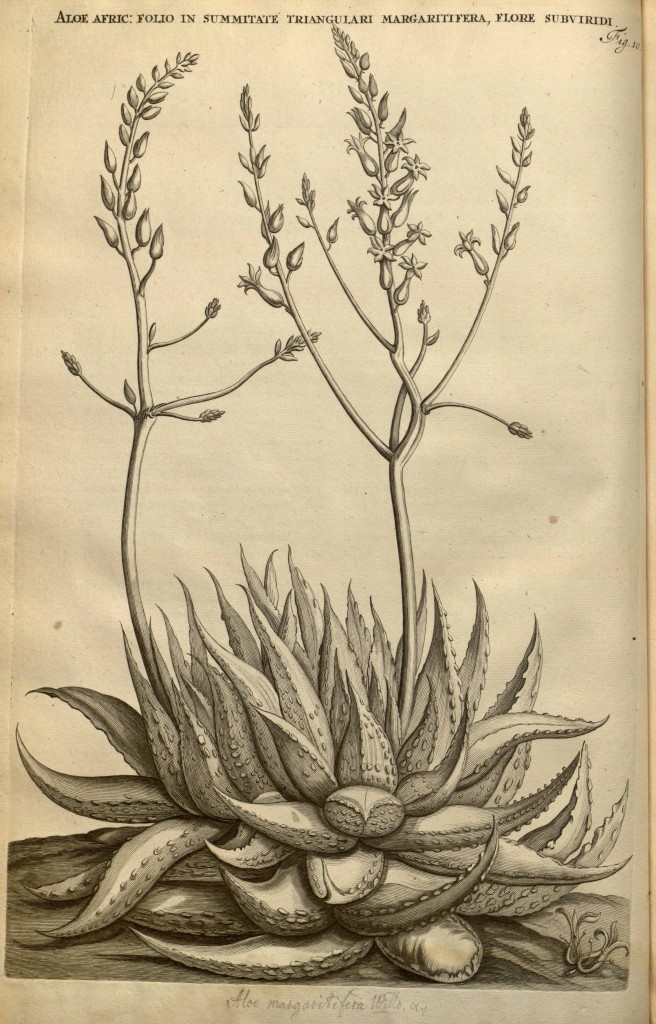

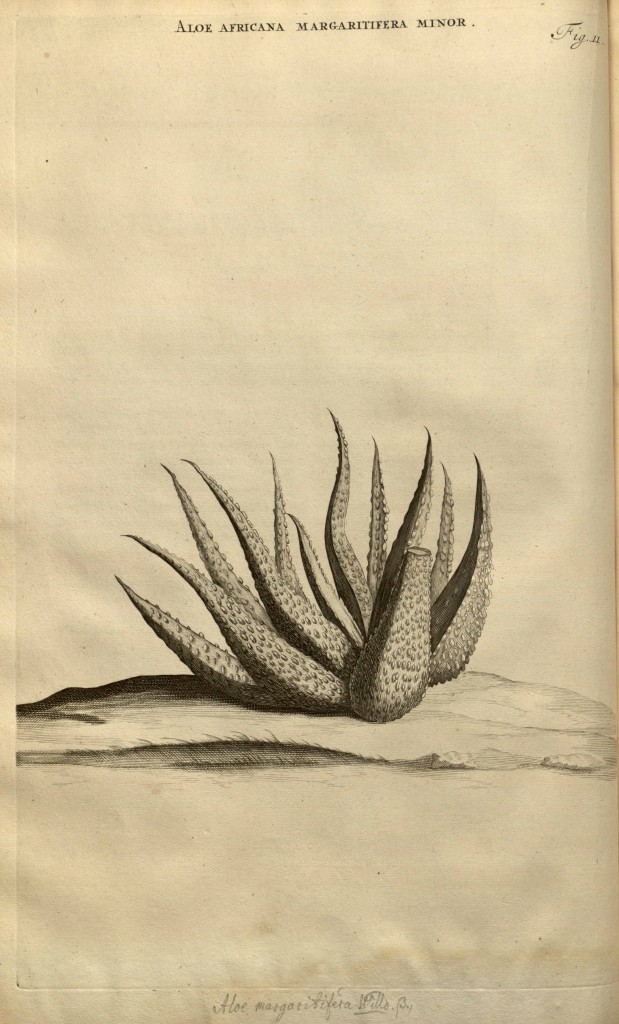

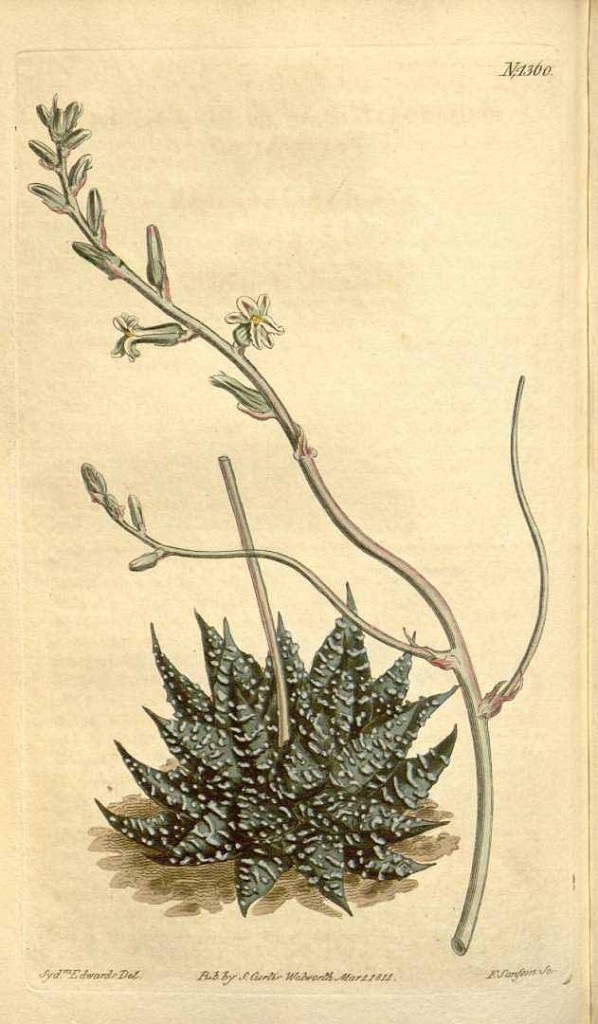

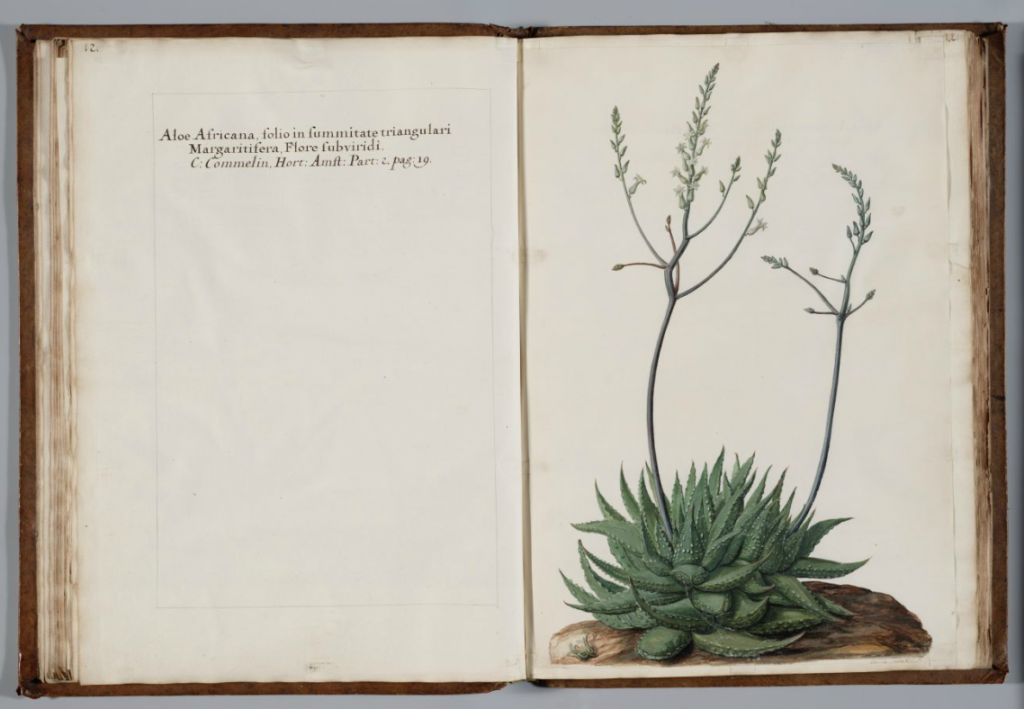

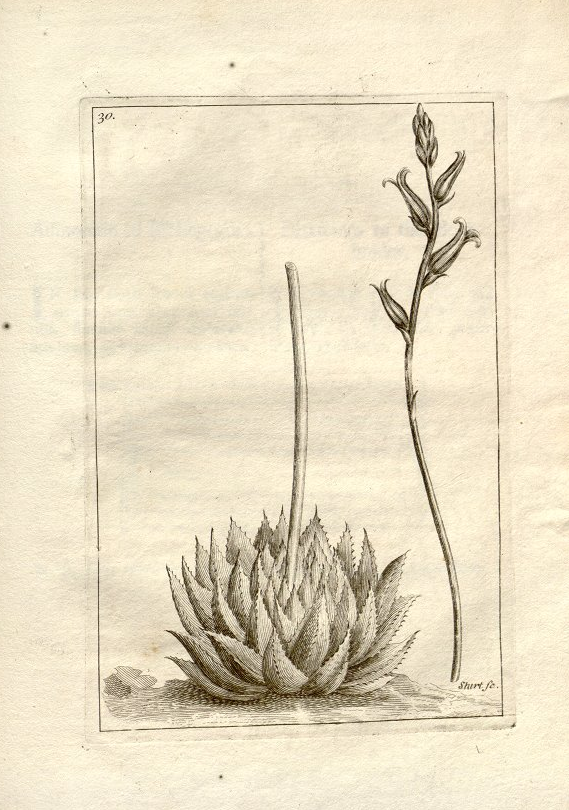

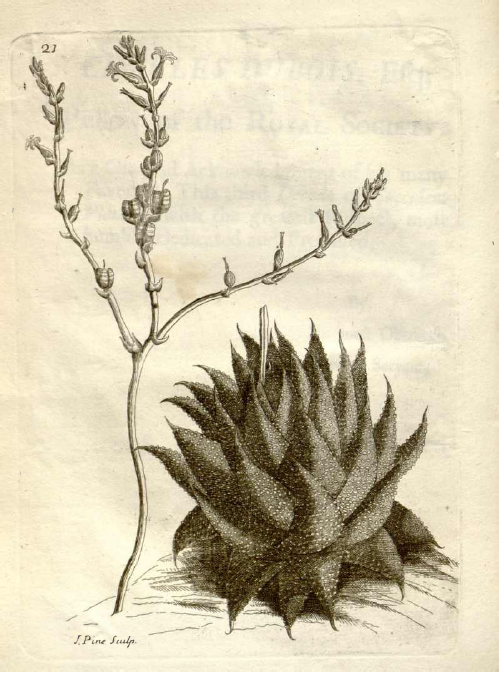

H. arachnoidea (L.) Duval in Pl. Succ. Hort. Alenc.: 7 (1809): Aloe pumila var. arachnoidea L. (1753): Catevala arachnoidea (L.) Medik. (1786): Apicra arachnoidea (L.) Willd. (1811). Lectotype, designated by Scott (1977): Commelin, Praeludia Bot.: t. 27 (1703). Epitype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Buitenstekloof, Langvlei, Bayer 153 (NBG).

= H. arachnoidea var. minor Haw. (1819).

H. arachnoidea var. arachnoidea

= H. joubertii M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 16 (2005), nom. inval. H. laxa M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 14 (2005), nom. inval. H. limbata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 16 (2005), nom. inval. *H. isomorpha *H. gilva

H. arachnoidea var. aranea (Berger) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 30 (1999): H. bolusii var. aranea Berger (1908): H. aranea (Berger) Bayer (1976). Lectotype: Engler, Pflanzenr. 33: 114, f. 39 A–E (1908). Epitype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Robinson Pass, Moeras River Drift, Bolus 12372 (BOL).

H. arachnoidea var. namaquensis Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 31 (1999): H. namaquensis (Bayer) Breuer in Gen. Haworthia 1: 7 (2010). Type: Karrachabpoort, Richtersveld, Bayer 1674 (NBG).

H. arachnoidea var. nigricans (Haw.) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 32 (1999): H. setata var. nigricans Haw. (1821). Neotype, designated by Bayer (1997): SW Vanwyksdorp, Bayer 2419 (NBG).

= H. helmiae V.Poelln. (1937): H. unicolor var. helmiae (V.Poelln.) Bayer (1976). H. venteri V.Poelln. (1939): H. unicolor var. venteri (V.Poelln.) Bayer (1976). H. scottii Breuer in Avonia 21: 55 (2003). H. nigrata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 15: 14 (2006). *H. apata *H. regens *H. formosa *H. kuromisa

H. arachnoidea var. scabrispina Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 34 (1999): H. scabrispina (Bayer) Breuer in Gen. Haworthia 1: 8 (2010). Type: Baviaans, Bayer 2105 (NBG) *H. matjiesta

H. arachnoidea var. setata (Haw.) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 34 (1999): H. setata Haw. (1819). Iconotype: artist unknown, specimen received from Dr Mackrill ex Cape (K).

= H. setata var. media Haw. (1821). H. setata var. major Haw. (1821). Aloe setosa Schult. & Schult.f. (1829). H. gigas V.Poelln. (1932): H. setata var. gigas (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1938). H. minima var. major V. Poelln. (1938): H. tenera var. major (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948). H. pectinis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 10: 13 (2003). H. tretyrensis Breuer in Avonia 21: 58 (2003). H. candida M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 16: 16 (2006). H. cangoensis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 13 (2005), nom. inval. H. angiras M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 13 (2005), nom. inval. H. kogmansensis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 14 (2005), nom. inval.

H. aristata Haw. in Suppl. Pl. Succ.: 51 (1819). Iconotype: (K). Epitype: Deadman’s Gulch (Soutkloof), Smith 3550 (NBG).

= H. denticulata Haw. (1821). H. lapis Breuer & M.Hayashi in Alsterworthia Int. Special Issue 7: 6 (2004). H. rava M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 11 (2005), nom. inval.

H. bayeri Hammer & Venter in Cact. Succ. J (US) 69: 75 (1997). Type: S Uniondale, Stayner in KG164/69 (NBG).

= H. hayashii M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 7: 14 (2002). H. laeta M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 13 (2004). H. indigoa M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 13 (2004). H. truterorum Breuer & Marx in Aloe 48: 54 (2011).

H. blackburniae Barker in J. S. Afr. Bot. 3:93 (1937). Type: Calitzdorp, Reynolds 1842 (NBG).

H. blackburniae var. blackburniae

H. blackburniae var. graminifolia (Smith) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 42 (1999): H. graminifolia Smith (1942). Type: Schoemanspoort, M. Courtenay‑Latimer in Smith 5222 (NBG).

H. blackburniae var. derustensis Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 41 (1997): H. derustensis (Bayer) M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 3: 13 (2000). Type: W. De Rust, Vlok sub Venter 93/24 (NBG).

H. bolusii Baker in J. Linn. Soc. Bot.:215 (1880). Type: Graaff-Reinet, Bolus 158 (K).

= H. odetteae Breuer in Avonia 21: 51 (2003). H. odyssei M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 11 (2005), nom. inval. H. capillaris M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 16: 16 (2006).

H. bolusii var. bolusii

H. bolusii var. blackbeardiana (V. Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Hand.: 31 (1976): H. blackbeardiana V.Poelln. (1932). Lectotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): ex cult. V.Poelln. 1932 (B).

= H. blackbeardiana var. major V.Poelln. (1937). H. inermis V.Poelln. (1932): H. altilinea var. inermis (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1937): H. altilinea var. limpida f. inermis (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1940). H. batteniae Scott (1979). H. calaensis Breuer in Alsterworthia Int. Special Issue 7: 5 (2004). H. specksii Breuer in Alsterworthia Int. Special Issue 7: 8 (2004).*H. hogsia *H. speciosa *H. malvina

H. bolusii var. pringlei (Scott) Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 62 (2002). H. decipiens var. pringlei (Scott) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 67 (1999): H. pringlei Scott (Bradleya 12:103,1994). Type: Adelaide district, Scott s.n. PRE 8970 (PRE). H. hisui M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 10 (2004). H. lazulis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 11 (2005), nom. inval. H. aquamarina M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 10: 13 (2003). H. hastata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 9 (2004).

H. chloracantha Haw. in Revis.:57 (1821): Aloe chlorocantha (Haw.) Scult. & Schult.f. (1829). Neotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): N Herbertsdale, Bayer KG411/75 (NBG).

H. chloracantha var. chloracantha

H. chloracantha var. denticulifera (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Hand.: 112 (1976): H. angustifolia var. denticulifera V.Poelln. (1937): H. denticulifera (V.Poelln.) M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 3: 13 (2000). Type (icono.): (B).

= H. angustifolia var. lilliputana Uitew. (1953).

H. chloracantha var. subglauca V.Poelln. in Kakteenkunde 9:135 (1937): H. subglauca (V.Poelln.) M.Hayshi in Haworthia Study 3: 13 (2000). Neotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Great Brak, Hurling & Neil (BOL).

H. cooperi Baker in Refug. Bot. 4: 233 (1871). Type: Cape, Cooper (K).

= H. vittata Baker (1871).

H. cooperi var. cooperi

= H. pallens Breuer & M.Hayashi in Alsterworthia Int. Special Issue 7: 7 (2004). *H. turcosa *H. elegans *H. foeda *H. yocans

H. cooperi var. dielsiana (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 51 (1999): H. dielsiana V.Poelln. (1930): H. pilifera var. dielsiana (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1940): H. obtusa var. dielsiana (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948). Neotype, designated by Bayer (1999): Sheldon, A.J. van der Merwe in Smith 1140 (NBG).

= H. joeyae Scott (1975).

H. cooperi var. doldii Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 65 (2002): H. doldii (Bayer) M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 11 (2005). Type: Chalumna, Dold 3961 (GRA).

H. cooperi var. gordoniana (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 52 (1999): H. gordoniana V.Poelln. (1937): H. pilifera var. gordoniana (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1938): H. obtusa var. gordoniana (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948). Neotype, designated by Bayer (1999): Patensie, Smith 3028 (NBG).

= H. harryi M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 9 (2004). H. jeffreis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 10 (2004). H. pusilla M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 10 (2004). H. ligulata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 6 (2004). H. venetia M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 6 (2004). *H. brandea *H. cineraria *H. compressa *H. gelatina *H. ionandra *H. neritica *H. silvicola *H. tomentosa

H. cooperi var. gracilis (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 64 (2002): H. gracilis V.Poelln. (1929). Neotype, designated by Bayer (1999): Hellspoort, Britten (PRE).

= H. caerulea M.Hayashi & Breuer in Haworthia Study 12: 7 (2004).

H. cooperi var. isabellae (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 62 (2002): H. gracilis var. isabellae (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 77 (1999): H. isabellae V.Poelln. (1938). Neotype, designated by Bayer: Humansdorp, Gamtoos bridge, H. Hall sub NBG 68799 (NBG).

= H. azurea M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 9: 12 (2003). H. arabesqua M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 7 (2004). H. bella M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 8 (2004). H. florens M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 11 (2004). H. pilosa M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 7 (2004). H. bathylis M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 15: 116 (2006). H. lachnosa M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 16: 16 (2006). H. ciliata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14: 11(2005), nom. inval. *H. kromia. *H. patriae *H. cuprina *H. dasylis

H. cooperi var. leightonii (Smith) Bayer in Haw. Hand.: 128 (1976): H. leightonii Smith (1950). Type: Kayser’s Beach, Smith 6938 (NBG).

= Haworthia leightonii var. davidii Breuer in Avonia 21: 49 (2003).: Haworthia davidii (Breuer) M.Hayashi & Breuer (2005). Type: SW East London, Breuer 6970 (TUAT). *H. sabita?

H. cooperi var. minima (Bayer) Bayer (2012): H. minima Baker (1880) hom. illegit. non (Aiton) Haw. (1812): H. gracilis var. minima Bayer [as (Baker) Bayer] (1999). Iconotype: (K).

= H. tenera V.Poelln. (1932): H. translucens subsp. tenera (V.Poelln.) Bayer (1976): H. gracilis var. tenera (V.Poell.) Bayer (1999): H. cooperi var. tenera (V.Poelln.) Bayer (2002). H. cummingii Breuer & M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 10: 4 (2003).

H. cooperi var. picturata (Bayer) Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 65 (2002): H. gracilis var. picturata Bayer (1999): H. picturata M.Hayashi (2000). Type: Enon, Thode 21507 (NBG).

= H. oculata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 10 (2004). *H. florida *H. imperialis *H. kubusie

H. cooperi var. pilifera (Baker) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 54 (1999): H. pilifera Baker (1871): H. obtusa var. pilifera (Baker) Uitew. (1948). Iconotype: Refug. Bot.: 234 (1871).

= H. stayneri V.Poelln. (1937): H. pilifera var. stayneri (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1938): H. obtusa var. stayneri (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948). H. stayneri var. salina V.Poelln. (1937): H. pilifera var. salina (V.Poelln.) V.Poelln. (1938): H. obtusa var. salina (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948): H. salina (V.Poelln.) M.Hayashi (2010). H. pilifera var. dielsiana f. acuminata V.Poelln. (1940): H. obtusa var. dielsiana f. acuminata (V.Poelln.) Uitew. (1948). H. luri M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 14:11 (2005), nom. inval. *H. sabrina

H. cooperi var. truncata (Jacobs.) Bayer in Haw. Rev.: 55 (1999): H. obtusa var. pilifera f. truncata Jacobs in Nat. Cact. Succ. J. 10: 81 (1955): H. ikra Breuer (2010). Neotype, designated by Bayet (1999): Runlets, Mgwali, Smith 5295 (NBG).

H. cooperi var. venusta (Scott) Bayer in Haw. Revis. (1999): H. venusta Scott in Bradleya 14:87 (1996). Type: NE Alexandria, Britten 781 (GRA).

H. cooperi var. viridis (Bayer) Bayer in Haworthiad 16: 65 (2002): H. gracilis var. viridis Bayer (1999). Type: Perdepoort, Smith 6867 (NBG).

= H. hamata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 10: 12 (2003). H. emeralda M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 11 (2004). H. subhamata M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 11 (2004). H. teres M.Hayashi in Haworthia Study 12: 7 (2004). *H. swannea

H. cymbiformis (Haw.) Duv. in Pl. Succ. Hort. Elenc.:7 (1809): Aloe cymbiformis Haw. (1804): H. concava Haw., nom. illegit. superfl. (1821). Neotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Port Elizabeth, Walmer, Smith 2844 (NBG).

= H. planifolia Haw. (1825): H. cymbiformis var. planifolia (Haw.) Baker (1880): Aloe planifolia (Haw.) Salm-Dyck (1840). H. cymbiformis var. angustata V.Poelln. (1938): H. angustata (V.Poelln.) Breuer in Gen. Haw. 1: 7 (2010). H. cymbiformis var. angustata f. subarmata V.Poelln. (1938). H. cymbiformis var. compacta Triebn. (1938): H. compacta (Triebn.) Breuer in Gen. Haw. 1: 7 (2010). H. planifolia var. exulata V.Poelln. (1938). H. planifolia var. planifolia f. agavoides Triebn. & V.Poelln. (1938), et f. olivacea Triebn. & V.Poelln. (1938), et f. robusta Triebn. & V.Poelln. (1938), et var. incrassata V.Poell. (1938), et var. sublaevis V.Poelln. (1938), et var. longifolia Triebn. et V.Poelln. (1938), et var. longifolia f. calochlora Triebn. et V.Poelln. (1938). H. planifolia var. poellnitziana Resende (1943). H. lepida Smith (1944). *H. cana *H. ingens *H. plena *H. rosea

H. cymbiformis var. cymbiformis

H. cymbiformis var. incurvula (V.Poelln.) Bayer in Haw. Hand.: 124 (1976): H. incurvula V.Poelln. (1932). Neotype, designated by Breuer & Metzing (1997): Pluto’s Vale, Britten s.n. BOL71307 (BOL).

H. cymbiformis var. obtusa (Haw.) Baker in J. Linn. Soc. Bot. 18: 209 (1880). H. obtusa Haw. in Phil.Mag. 46: 282 (1825). Iconotype: (K).

= H. umbraticola V.Poelln. (1937): H. cymbiformis var. umbraticola (V.Poelln.) Bayer (1976). H. hilliana V.Poelln. (1937): H. umbraticola var. hilliana V.Poelln. (1938). H. obtusa var. pilifera f. truncata Jacobs. (1960). *H. blinkia

H. cymbiformis var. ramosa (Smith) Bayer in Haw. Revis.: 60 (1999): H. ramosa Smith (1940): H. cymbiformis f. ramosa (Smith) Bayer (1976). Type: Wooldridge, Smith 3168 (NBG).