by J.M. “Essie” Esterhuizen and M. Bruce Bayer. While Bruce Bayer is the writer of this piece is by convention prime author, Essie Esterhuizen is cited as such for the following reason; it honours an astonishing amount of field work and profound insights that many taxonomic botanists never acquire. It is instigated by Essie’s more recent exploration and comments he has made that reflect the writer’s own conclusions. Thus this article is intended simply to mirror the thoughts of open minds looking for answers in a domain dominated by academics.

Introduction and general preamble

The two of us have been long interested in nature and particularly Haworthia. We have a combined experience of at least 120 years of exploring the subject that we would like to share. Neither of us makes any claims to some or other authority or qualification that gives us more authority than anyone else. We have simply had an enormous privilege to have spent so much time in the field learning about these fascinating plants. Just like anyone interested in anything, we have needed a vocabulary and words or names to understand, organize and communicate our thoughts and words. This is either as internal private mental processes or as external communication with other people. The most important words we need are designations and names for the very objects of our interest. Perhaps for our own purposes we do not need words at all, but for external communication we certainly do. Then it becomes problematic because agreement, definitions and all kinds of conventions and guidelines exist that may not correlate with our individual capabilities, character, belief or value systems. In fact all this may clash with what our deepest individual understanding tells us.

The facts are that we have an organized system of information gathering and exploration we term ‘science’. Within that we have various disciplines of which botany exists for the plant kingdom. Within that we have a sub-discipline (taxonomy) of description, identification and classification. To guide this process international rules of nomenclature are agreed upon to provide a powerful framework of names that Essie and I now try to evaluate as a framework for our observations in that group of plants we know as Haworthia. Already there is a problem because Haworthia have been known in history as Aloe at the birth of the Linnaean system before being separated as Haworthia. At present there is one faction that maintains this arrangement and another that expounds Haworthia senso stricto, Haworthiopsis, and Tulista as a formalization of three distinct sub-groups (subgenera) that both of us have no problems with.

This all seems very good and well until one faces the harsh reality that science as a discipline is concerned with physical creation. Rather than serving the purpose of information gathering across every single aspect of sentient life, it is in fact restricted to what has been described as mechanistic materialism. This is where explanations are sought for anything and everything by processes of experimentation, measurement, analysis, reason and logic. Plant taxonomy, at its base, rests on the principle that there are basic life forms (species) as in the animal world and that there are basic discrete life forms kept apart by virtue of their closed reproductive systems. This is derived or adapted from zoology and tacitly transferred to botany when there is enough evidence to demonstrate that fertility can extend across generic barriers. There is in fact no species definition. There is also no recognition of metaphysical realities or even the possibilities of their existence. Curiously a formidable intellectual who has edited and largely authored a massive six volume encyclopedia of mystic terms by John Davidson M.A. (Cantab) concluded that the definition of the species concept as a basic life form was not the same for science and mysticism. This is patently absurd.

Endless debate can ensue, but Essie and I, in our quest to understand Haworthia, have simply wanted to know what these basic forms are in practical terms so that we can organize and communicate our interests and thoughts with each other or with anyone else that may have common interest. In our quest we have simply used the hundreds and hundreds of names that have been coined for Haworthia species to come to know what these tell us and how useful they are to us in understanding them. Rationally each name is based on the tacit perception that it applies to a group of plants that are, or potentially are, interbreeding. This is blatantly untrue and no good definition actually exists to our knowledge that in any way regulates what is formally described as a species. An example could be cited where a single plant specimen has been selected to represent a hypothetical, fictitious species. No name in mentioned to avoid hurt. So we (the authors) have labored under this handicap where no one knows what a name even means, in trying to use and apply the many names sensibly. Both of us have written extensively about our field experience and what we will do now is collaborate in this article to explain how we have used what is available to explain the relationship of various populations. This is with the recognition and realization that the plants occur in highly localized limited localities, are highly variable and yet somehow seem to be integrated and related according to a geographic modality.

It is simply not rational that we may only confidently apply one or other of the many names if we know where a plant comes from. Lawrence Loucka has done an incredibly good job in creating a compendium of Bayer’s writing in a website Haworthia Updates (https://haworthiaupdates.org/). This culminates in a set of what were Facebook postings (in Haworthia Shucked ) under the title “Mysteries”). In these, particularly “part 36”, it is posited that named species such as retusa, turgida, mirabilis, mutica, pygmaea and emelyae are in fact one and the same species. All Bayer’s writing since the publication of his Haworthia Revisited in 1999 is in pursuit of the goal that Essie independently undertook circa 1980 viz. Just what constitutes Haworthia in respect of different life forms that intrigue all of us even it we do not cognitively know this. The section “Mysteries” in Haworthia Updates deals specifically with Bayer’s exploration in the Albertinia area while Esterhuizen has evidence from an additional six localities that provide the very evidence that Bayer was expecting and looking for.

Together we thus consider that the six species are in fact one single system according to a definition of plant species that we agree on and repeat here … A species is a complex dynamic conscious fractal system of living organisms that are metaphysically, and physically (genetically, morphologically, physiologically, behaviorally) continuous in space and time. It seems logical that these systems must be open as it the same one consciousness that pervades all of creation, and surely that is incontestable. Furthermore there is constant change and not necessarily at all in an interminably slow Darwinian selective way. Both of us have observed dramatic changes within our time spans of observation.

The evidence

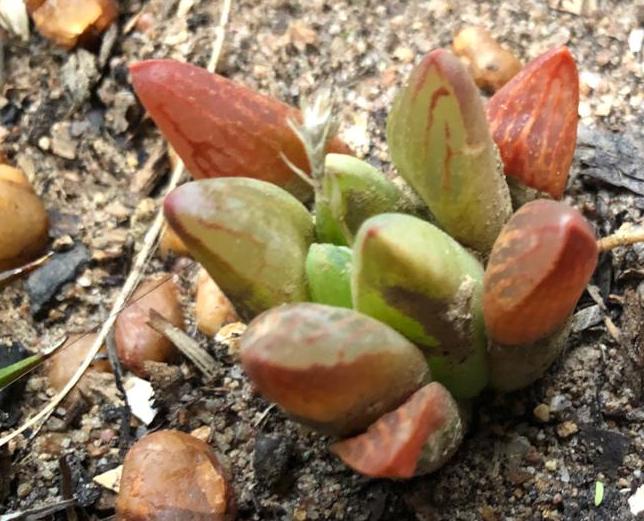

The evidence for our conclusions is in fact already out there in Haworthia Updates and also in Essie’s more recent Facebook Page Haworthia Veld Memories (https://www.facebook.com/Haworthia-Veld-Memories-110859041540965/). Here we simply post a selected set of 54 pictures of plants from 27 populations from between Riversdale and Albertinia to as far east as Great Brak, east of Mossel Bay. The published names, primarily of species (sic!) rank our present discussion covers are the six already named viz. retusa, turgida, mirabilis, mutica, pygmaea and emelyae, and then fusca, splendens, dekenahii, argenteomaculosa, acuminata, rodinii, pallidifolia, suberecta, esterhuizenii and vincentii. There are no doubt many more names that sprout from a need that should not be met by resort to formal botanical taxonomy or nomenclature. No further discussion of those names is deemed necessary because that is what the literature on the subject already does.

Very important in consideration of these pictures, is the question of randomness and bias. The pictures we have selected were based on selecting what is reasonable from those that are available. Unfortunately the range of pictures available is generally very limited for most populations. Secondly it is difficult to avoid any kind of bias when photographing. Populations can be extremely variable and one can select pictures to either prove similarity or difference. This needs then to be adequately weighted to geographical relationships and habitat. As an example of the latter point is that it the contention of the authors that turgida is really a cliff hanging variant of a flats dwelling retusa. Just how does one formulate a single image from a mélange of different ones? This is probably where the difficulty really lies in reaching agreement because we may simply be doing so differently.

Essie’ perspective.

(I have adapted Essie’s direct written contribution to this third person version to try and get a better fit …) Understanding Haworthia is like putting together a giant jig-saw of many thousands of pieces. Only nature knows the full picture, and we will only see that if we can complete the puzzle.

The difficulty we truly struggle with is this. If we try and apply the many names made available to us for plant populations we do know, to further new populations we come across in my field jaunts, we end up nonplussed and confused. In fact sometimes a name applied to some or other population does not seem appropriate even for many of the plants in those same populations.

Essie grew up in Heidelberg so it was just logical that H. heidelbergensis would be the first species he came to contend with. It was described as coming from under one bush just west and practically within Heidelberg itself. What he found there did not match what Smith or anyone else wrote or said. Later he found a second population nearby in which there was nearer agreement at least with the original description. But he also looked at about 10 other populations in the general area and could not imagine how one could apply the criteria of the description to all the variants he was seeing. As originally selected and described, H. heidelbergensis is not even representative of the population from which it came. He had a similar experience with H. turgida that occurs abundantly in and around Heidelberg. It just seemed irrational to formally recognize all the variations. His exploration further east of Heidelberg gradually lead him into a swamp of variables and names that included amongst many more H. heidelbergensis, H. magnifica, H. retusa and H. atrofusca. He could not see or decide where one started or stopped or how the descriptions could possibly explain the situation.

Widening his exploration still further to the east and then west, south and north simply added to his dilemma. Just where did a “species” stop or start? H. dekenahii was a particular problem for him because he saw it change status from a discrete species to a variety of either H. mirabilis, H. pygmaea or H. retusa. He ended up in a situation that he could not give a name to a plant unless he knew where it had originated. This is not something any of us would like to admit to because there are four reasons for the unfortunate truth of the issue. Firstly there is the extraordinary intrinsic genetic variation of the plants themselves, secondly the variation coupled to age and growing conditions (in the field or in cultivation), thirdly the extraordinarily idiosyncratic way in which names are generated and imagined to have meaning, and lastly what we all do have to admit to viz. personal perceptions.

Concluding remarks

No formal taxonomic alterations are suggested. The communities and persons involved and interested in these plants need names and we still use names just as if they never disappeared from a formal revision and new classification. Bayer suggested in his very first Handbook (1976) that it is quite unnecessary to consider names as lost just because a taxon is no longer regard as formally valid. It seems foolish to us to expect formal taxonomy to submit to a hobbyist interest, even though it should definitely underlie whatever names are used there.

More important is the idea put forward here that H. retusa and H. mirabilis are a single system that cannot be subdivided into any set of names with equal rank. It does not offer any solution in respect of better delimitation of other species. We have not presented any evidence regarding H. emelyae for example, or how species like H. herbacea and H. reticulata relate to the system we have covered here. The article does not touch on a definite and incredible role that H. floribunda plays as part of the puzzle. Nor on the intricate close relationship this species has with H. chlorocantha, H.variegata and H. parksiana. Furthermore we are both acutely aware that the same complexity is evident among other acknowledged species. So even having a species definition is not resolving the issue of names.

Dr. Davidson has suggested that perhaps the metaphysical element needs to be explored and understood. What this means is that we cannot to continue believing, as “science” intends us to do, that consciousness has evolved in creation. Instead it is creation that has evolved from consciousness. Rather than cite any references to this concept we suggest searching the internet on the topic. The conclusion really seems to us that the systems, organizations and individuals (tasked or self-anointed) to describe and name plant species and their variants, are simply not up to the task. This is largely because of a paradigm of science that is self-limiting.

End note

While drafting this article I learned that Davidson has in fact authored a book ”Natural Creation or Natural Selection”. I would have asked “Intentional Creation or Accidental Creation”. Unfortunately too few of us are intellectually up to arguing the subject and it seems to me that our whole society has been dumbed down and fooled into believing that we human beings are the central and most important entities in creation viz. anthropocentrism. There is another belief paradigm that all forms of life have intrinsic value viz. biocentrism. Personally I favour this point of view, even going so far as to say that it underlies this curious preoccupation and brotherhood I feel with Haworthia! There are other authors such as Capra, Sheldrake and Meyer that emphasize a creation that stems from consciousness rather than the converse.

Acknowledgement

Both of us have an enormous debt to the incredible number of people who we have touched on our journey and the best we can do is just adopt an attitude of great gratitude for all the interactions great or small, our last hurrah.

Suggested literature

Capra, F. The Web of Life, Anchor Books. 1996

Davidson, J. Natural Creation or Natural Selection, Vega Books. 2012

Roads, Michael. Talking with Nature, Journey into Nature, Six Degrees Publishing Group. 2018

Sheldrake, Rupert. A New Science of Life, J.P.Tarcher. 1982

Meyer, Steven. Darwin’s Doubt, Harper One. 2010

Pingback: Mirabiloid continuum of the Lower Goukoe River - Haworthia Updates