When I wrote the first part of this essay, I was anticipating completing it in three parts. However, I was also in the process of exploring more widely and thoroughly, and the problem and its explanation seemed to grow exponentially. The result was seven essays, and they are presented here as close as possible to their original format. The purpose is to show how a classification should have predictive value, and how an understanding of plants can develop, or fall apart, as more information accumulates. The seven parts were published in Haworthiad 17:1:24-32, 17:2:53-54, 18:1:21-33, 18:2:52-57, 18:3:92-101.

Part 1: Haworthia mutica var nigra indeed!

An early problem in my career as a Haworthia taxonomist was that I had plants of H. mutica which I could not distinguish from plants of H. pygmaea. The former is from the Caledon/Bredasdorp area in the west, and the latter from Albertinia/Mossel Bay in the east. I had also had a collection between these, from Kransriviermond south of Heidelberg, which did not fit comfortably with my perception of H. retusa at Riversdale, or with either that of H. mutica or H. pygmaea. I was also stuck with the probability that there could be other continuities by virtue of unrecorded and unknown populations. A known troublesome population was that from south of the Tradouw Pass that I eventually included in a wider interpretation of H. magnifica, however uncomfortable that was. A problem here is that in separating magnifica from maraisii as species, and in also recognising the variety H. magnifica var. atrofusca, the closer identity of magnifica gets lost in a fragmented residue. As will be seen in the following discussion, this also relates to the understanding of H. mutica var. nigra.

While there was initially a limited amount of material to go by, it might have been thought that more collections would clarify the problems. Instead it became increasingly evident after my first two handbooks that additional collections were confounding the picture even more, and they certainly have. Esterhuizen made the first of such collections from Klipdrift, northwest of Heidelberg. Then there were two populations recorded by Venter, from east of Heidelberg and southeast of Heidelberg. I did not have material of Esterhuizen’s collection but mentally included it with the Tradouw pass population as H. magnifica var. magnifica. The last I included in my concept of H. mutica var. nigra while I was not immediately certain what to do with the population just east of the town of Heidelberg, close to where H. heidelbergensis occurs. I knew these retusa-like plants from photographs and specimen in G.G. Smith’s record. They are very similar to the Klipdrift plants except the habitat is again slightly different and the plants are solitary and the leaves level with the soil surface. It should be noted that I drew attention to this aspect before, when I suggested that H. retusa was in reality a ecotypic adaptation to level ground as is the vegetatively proliferous turgida the adaptation to steep rock faces. The problem was lack of material and the best I could do then was to predict continuity between mutica and retusa. Thus the variety nigra was out of the geographic areas of either and yet not substantial enough to suggest that it was a separate SYSTEM. I have since seen Smith’s plants live as JDV90/113 in cultivation and in the field.

In the last two years I have paid more attention to H. mirabilis and the disconcerting variability of this species. A closer study of the var. sublineata has produced a dismaying degree of variability and I do not doubt that an argument could be made on this score for including the Tradouw Pass plants under H. mirabilis. This is not as improbable as it may seem if all the variants are considered such as in H. heidelbergensis, H. maraisii, H. floribunda. Experience with the Eastern Cape complexes also leads me to predict that these western species are similarly going to be inextricable from one another.

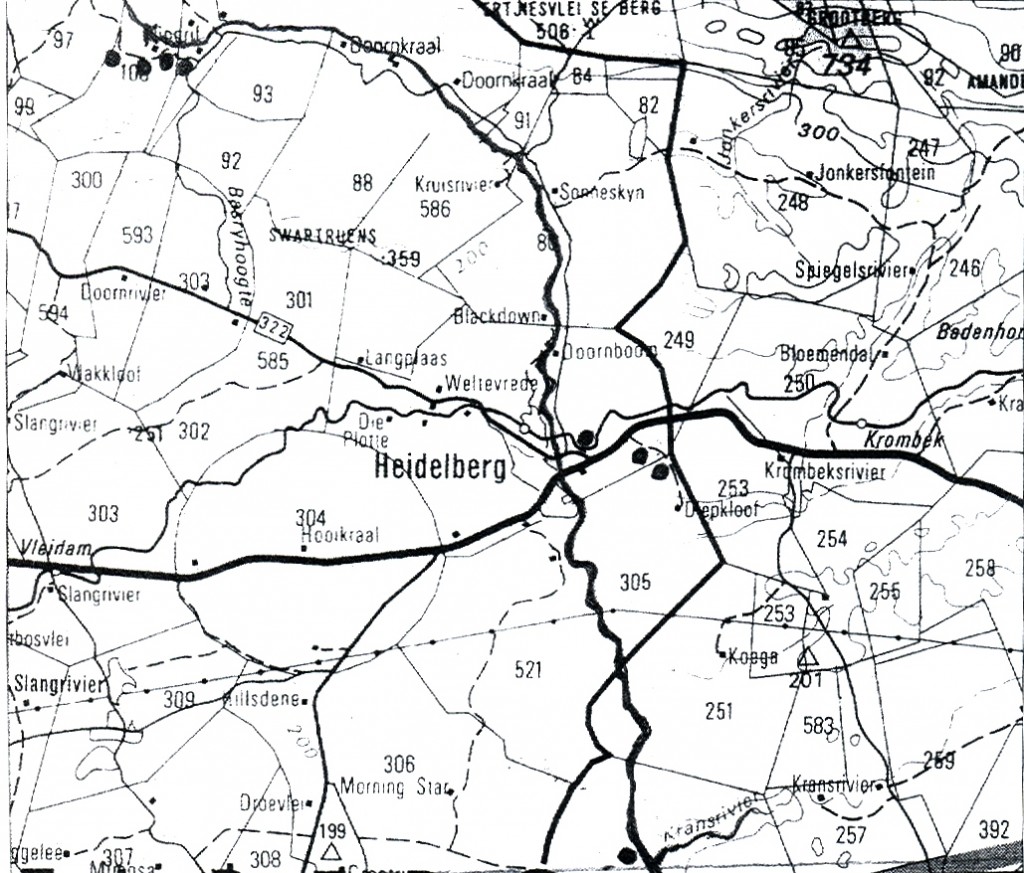

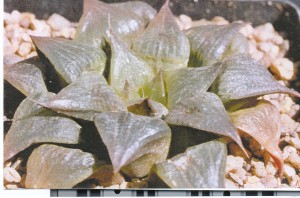

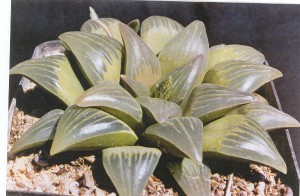

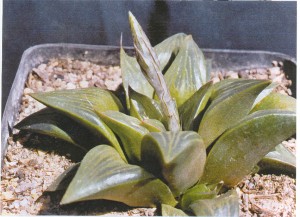

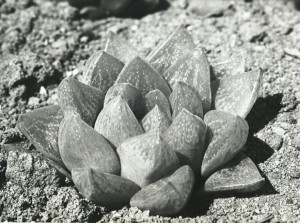

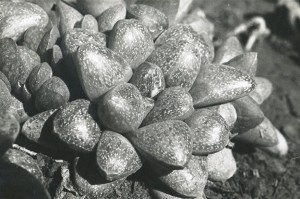

Without proposing another solution, other than for the Tradouw plants, I needed to first explain the Esterhuizen population. Here I was fortunate to have the interest and hospitality of Dr. Christie Venter who grew up on a farm just to the northwest of Klipdrift. He now has a property near Zuurbraak where he accommodated my wife and I and we were able to explore the Klipdrift area (see map, Fig.1) to good effect. We found four populations along the southern side of the Duiwenhoks River, two on Goedehoop (Figs.2 & 3) to the west of Klipdrift, one on Klipdrift itself (Figs.4, 5 & 6) and another on Doornriver to the east (Fig.7). From there we went to the two sites east and southeast of Heidelberg (Figs. 8, 9 & 10), as well as to a further population midway between these two. We also revisited the familiar locality for H. heidelbergensis east of the town.

What do these populations suggest and what is the solution? These plants do not fit the bill for H. magnifica because they lack the deep dark colouration of that species or the generally shortened leaves. They do not fit with H. mirabilis because the leaves are generally more recurved, the reverse of the leaves is less spotted, and the surfaces are generally smoother. The geographical location does not agree either. The plants cannot be placed comfortably with H. turgida var. turgida, which is a smaller more spinose and clustering species in sandstones. There is some correspondence to H. turgida var. longibracteata and also to H. retusa. From the latter it differs in having fewer more recurved and less spinose leaves, while from the latter it differs in being smaller, more translucent and with narrower more erect leaves.

There actually does not seem to be a categorical answer, which is just what I would have expected. There seems to be this pointer to the new language we need, where we agree on the meaning of names in a fairly arbitrary way. I suggest that for the present this group of populations of doubtful identity should be treated as H. mutica var. nigra. I am quite conscious of the fact that there is an opposition body that wishes to re-interpret such doubtful elements as even H. asperula, and probably produce an entirely different classification and new names. I respect this point of view and it was Prof. G.F. Smith who stated in the introduction to Breuer’s book The world of Haworthia, Vol. 2, this is a golden age and we are each now able to make our own decision! For communication purposes it would be wise if we tried to agree on one set of names. Simply each of us naming plants as species as they come before us has no intrinsic meaning or message for anyone else. It will work for a closed group in close contact with one another, and all seeing and talking about that limited range of specimens. For me who has seen so many plants over so many years, it just becomes quite meaningless. It means that we have a set of names which has no practical value for anyone outside of that group and nor does it have any value for say biologists or scientists working in other disciplines where the names have to have meaning in the broader sense of biological systems as applicable to all life forms.

Fortunately there seems to be an awakening in the botanical fraternity to the fact that our classification system and the notion of a branching tree with the species dangling on the straight branch ends, is faulty. One only has to think what happens when we have a species and then describe a variety of that species. The nomenclatural system requires that a typical variety be automatically created. The implication is that the two varieties stand equal to one another – and this is patently and obviously untrue and unworkable in practise. It actually means that while the variety may be fully distinctive and even be derived from a single always fully recognisable clone, the typical variety has to accommodate every other variant in the species. Thus the more varieties that are described, the more shattered, indefinable and unrecognisable is the “typical” variety. In this is just how it should be if we properly and logically think about distribution of phenomena in space and change with time. Where subconsciously we probably think of species as very definite definable things, the reality is that it may only be individuals (individual clones and vegetatively propagated plants) that have any individual recognisable identity. It is just a myth to say that in a species, the flowers of the individuals are always all similar (identical), or that the leaves have this special character – and so on. If readers are familiar with Haworthia Update Vol.1, they will appreciate that considerably more illustrations are required to truly reflect the relationships of the populations I discuss here and extend this to the broader geographic area i.e. H. heidelbergensis, H. magnifica, H. maraisii, H. mirabilis and others.

A consideration I must add is that the question of very local adaptations to habitat complicates the picture enormously. Thus the complex geology, topography, and climate of the southern Cape are as important as reasons for the extremely rich and variable flora as may be any history of the origin of vegetation from a distant past. Here I am dealing with just the drainage systems of a small river, the Duiwenhoks, which runs from north-west of Heidelberg first towards the south-east and then south to the sea. Other “species” in the close area are H. heidelbergensis, H, turgida and H. magnifica (note that the variety atrofusca thoroughly obscures the identity of the typical variety, and this is further clouded by other varieties, what to say of some of the names now proposed for elements within this huge complex).

Part2: Consequent to Haworthia mutica var nigra indeed!

I omitted illustrating JDV90/113 and of plants from the type locality for H. mutica var. nigra from Part 1, stating simply because these two populations lead from that system to another further east that is more complex. But this is not quite true. What is true is that G.G. Smith was considering the population later collected as JDV90/113 (as a single plant too, no doubt) to be either a new species or a new variety of H. retusa. What is thus difficult to explain is that it is not just a question of how this population related to H. retusa or to H. mutica. It is a problem of how is it related to either of these complexes that have their own internal as well as other external associations (see figs 11 & 12).

In the case of H. mutica var. nigra (Figs. 11 & 12) itself from Kransriviermond, I did not happen to have a picture then available and in any case it is illustrated in Haworthia Revisited. With this short note, the position was rectified and pictures of both collections are provided. It can be noted that JDV90/113 (Figs. 13 & 14) is within 50 meters of the population that I took to be the type locality for H. heidelbergensis. There are not many plants and they are solitary and the leaf surfaces are level with the soil surface. This is the general pose for H. retusa where it grows exposed on level habitat (see figs 13 & 14).

Why have I then not called these plants H. retusa? It is because I considered there was a continuous range of populations that linked H. retusa and H. turgida, and the Kransriviermond population was at variance with this opinion. It is of course equally valid to say that the plants I have illustrated as H. mutica var. nigra could also be regarded as possibly continuous with either H. retusa or H. turgida, as well as include some influence from either H. magnifica or H. heidelbergensis or both.

So what more needs to be said that can be said? An explanation really only begins to make sense when all the role players are examined in detail. H. mutica cannot be represented by a single plant and neither can H. retusa or H. turgida or H. magnifica. Even when one has all these myriad collections in front of one, one wonders what more is there which will cloud the issue further! It is evident that we tend to seek an answer in an easier two-way comparison, when the solution is a much more difficult manifold or reticulate relationship.

Part 3: Still consequent to Haworthia mutica var nigra indeed!

In this part of the essay I discuss what I refer to as “the distant turgida connection”. In the two preceding notes I commented on the problem of using the name retusa in connection with H. mutica var. nigra. It was not unduly surprised to read that Esterhuizen claimed that nigra was rather a variety of retusa than mutica (Alsterworthia). This observation of his is perfectly valid and only misplaced in the context of what I had written before, and as far back as the original Haworthia Handbook. Where the difficulty lies, apart from the intrinsic difficulty of the problem, is with our so-called “typological” concept of species. Thus we form a mental image of, say, H. retusa from an illustration, either the original type illustration: or one that has been chosen to resemble that original. Then we build images around the name of other plants that we come to know as H. retusa. But these images are seldom composite ones that accommodate all the variations and are also limited by how much we have seen. Similarly we then generate images of, in this case, H. turgida and H. mutica and then try to weave them together into a single mental construct.

In this case the introduction H. pygmaea would be somewhat of a surprise. But I did say at the start that one of my very early disconcerting experiences was having plants of H. mutica and H. pygmaea, and finding that I could only separate them on the basis of known origin and the colour of the floral bracts. Without going into the lengthy detail of the variation of H. pygmaea and its associations which include H. turgida and thus to H. retusa, briefly the tale is this: It can be taken as read that the colour of the bracts is not diagnostic for any Haworthia species, where all we then have in this particular instance is geographical information. These single images we build leads to confusion and to misapplication of names. When we think we are specifying, we are actually making very general statements, which in turn help to confound attempts at identification and classification.

Therefore I want here to just illustrate some variants of H. turgida in order to provide a broad image of this species so that its role in the tale can also be guessed at.

I do this for six reasons:-

1. I started a series of articles with the grandiloquent title “Natural variation and Species Delimitation in Haworthia”, for the National Cactus and Succulent Journal way back in 1972. One of the manuscripts I started concerned H. turgida. I had a vast amount of material and I was rather stuck as to how to illustrate it all. It was also obvious that there was a great deal more to see. So the project was shelved until now when this discussion generated the need.

2. While going through my files, I found a few of the old pictures I would have used.

3. I think that readers should be made aware of this major pitfall of perception now that so many writers are in the arena.

4. In addition to H. turgida, the following cannot be positively excluded from reckoning: H. retusa, H. heidelbergensis, H. mutica, H. maraisii, nor H. magnifica. Other authors are very industriously adding new names that will cloud the issue still further.

5. I still would like to see more H. turgida and more H. retusa. I am now quite well positioned in terms of new material, to write about the other elements.

6. The literature is now fragmented beyond sensibility and it is difficult even for me to follow it all and keep a chronological account of what is written there. Other writers have the same problem while they are not even paying proper attention to what has gone before. This is of course their prerogative; and that of the editor who permits his authors to wander where they will.

I do agree with Esterhuizen’s contention that H. mutica has not been found east of the Breede River, which could suggest that the relationship of mutica var. nigra is better sought with H. retusa. However, this would make sense if the typological concept of species was sound and if the concept of the phylogenetic tree with sequential single-branching stems was true. The fact is that one can find the characters that we might use to diagnose any one “species” across the board. Thus I can find “nigra” or similarities, in populations of turgida, retusa, heidelbergensis, magnifica, maraisii and mirabilis. Esterhuizen is quite happy (I have done so myself and it is no criticism) to use the name retusa for plants from near east and even west of Heidelberg, when in fact there is exactly the same problem of “identity” at Riversdale and beyond. This is that retusa is probably an ecotypic variant of turgida. Forget that the name retusa would have precedence over turgida if the taxonomic chips were down.

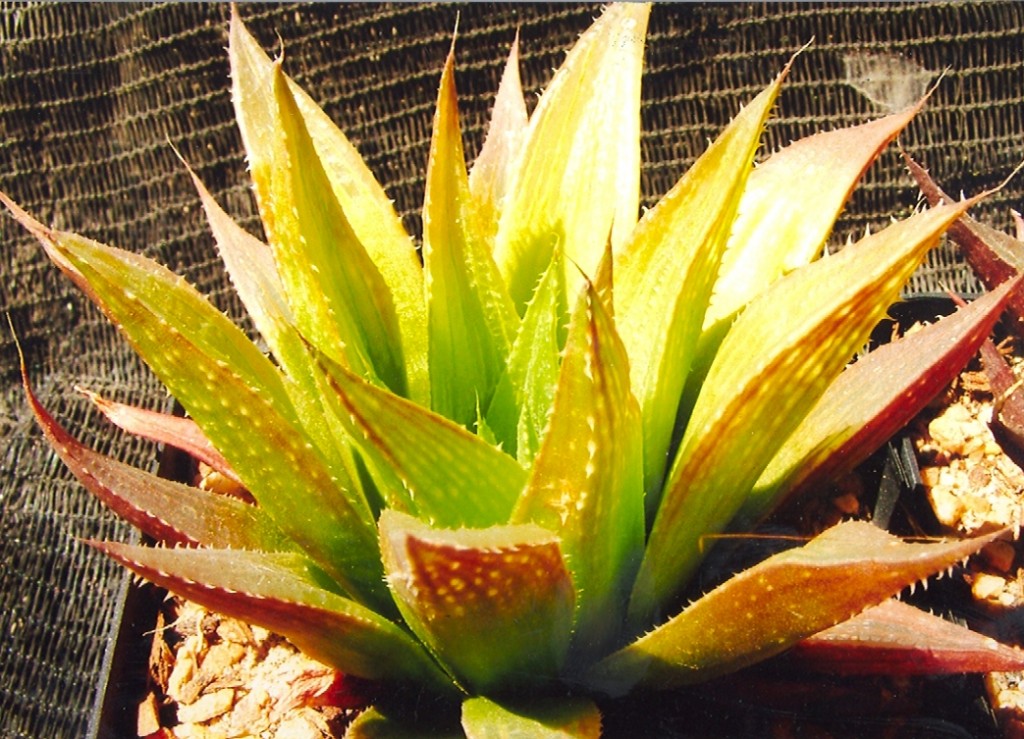

The first three illustrations (figs 15, 16 & 17) are of H. turgida in a sequence from north to south towards Heidelberg. I choose (chose) this sequence because “turgida” is the sandstone ecotype, and these populations suggested to me that there was a continuous set of populations which linked “turgida” to the more solitary clay-soil, level-ground, silcrete-hill “retusa”.

Perhaps I should also emphasise the point that I am using single clones to illustrate populations and systems – where this does not actually work. It is already an approximation. Immediately north of Heidelberg, there is a problem where turgida merges with heidelbergensis. Heidelbergensis itself has its origin in a few plants found beneath one bush, 0,4km West of Heidelberg (I was wrong in following Dekenah’s contention that the type locality was the population 0,4km east, and also heidelbergensis is extraordinarily abundant and variable just west of Heidelberg). It is apparent that the concept of heidelbergensis is based on the interface of two systems viz. turgida and one other. This “other” carries the name “heidelbergensis“, and I will in due course present some of the very extensive ramifications that have emerged in the last few years concerning this particular problem.

The next three illustrations (Figs 18, 19 & 20) are from populations quite some distance from the sandstone range of the Langeberg Mountains (which is the main “turgida” domain), for which I use the varietal name longibracteata. I could not really censure Hayashi for finding new names for any of these. There are several other such non-sandstone populations that I should illustrate, and I know I have not seen them all. I add two illustrations (figs 21 & 22) of the var. suberecta for the eastern forms of “turgida“. To finally knock a nail into the coffin, I add a picture (fig.23) of H. mirabilis var. consanguinea from the Riviersonderend sandstone mountains south of McGregor. Why I name it “mirabilis” is for very good reason, and this reason is as complex as is the full “turgida” saga or that of others. It is thus very frustrating to read simple solutions that are being presented by writers who in my opinion just do not have the competencies or material to do so authoritatively.

Part 4: Still on about Haworthia nigra var mutica.

When the previous Part 3 of this small series was published, a few words were omitted from the title. These were, “The distant turgida connection”. This part could have been entitled the close retusa connection. What I was actually looking for was a more definitive explanation and I could not find it. In writing about the relationship of H. floribunda, both Esterhuizen and myself have assumed that the plants I attribute to the species H. variegata viz. the varieties hemicrypta and modesta are in fact that species. It is probably truer to say that they are not and that they are simply part of a much larger complex system for which classification solutions are right for one part of the distribution range and wrong for another. I say this because in this article I will be using the name heidelbergensis in the same way (in the text all references will be in terms of the typical variety. Technically there is no population of this species in which the plants all generally resemble those from which the type was supposedly derived).

What I want to write about is a series of populations from east of Heidelberg that really throws a cat among the pigeons. There is a low flat plateau between Heidelberg and Riversdale named Kiewietskraalse Vlakte (to be referred to simply as Vlakte) at an altitude of 300m (see map Fig. 24). It is divided into three farms, Kweekkraal East, Kweekkraal West and Melkboom further west. The area to the east, north and west is very broken and generally unsuitable for cultivation. Southwards the terrain is lower-lying at about 150m and is largely cultivated. The pattern of cultivation suggests that the soils in that area are arable and hence were never really suitable habitat for Haworthia. This is an assumption based on where haworthias are found in the greater area and this is invariably on sites where the soils are very skeletal and where rock is exposed. Often these sites are on broken profiles of erosion channels or small hillsides, perhaps for the presence of harder and less erodable rock. This is not to say that there were no suitable habitats on the level areas and certainly the four species of the Robustipedunculares are/were less confined by habitat requirements than members of the subgenus Haworthia. Assumptions about occurrence and suitable habitat are important because they relate to the degree of isolation of populations, to the role of geology in the evolution of ecotypes and hence to the taxonomic relationship of those populations. My impression is that cultivation has generally not impacted on Haworthia populations.

On Vlakte the vegetation is Renosterveld. It has numerous buttresses and surrounding it are a few separate inselbergs. The upper level areas are cultivated and where the natural vegetation is still intact, haworthias are still only found in very specific and identifiable habitats. The eastern-most inselberg is Spitzkop that is the type locality for H. magnifica var. atrofusca. H. retusa in its classic form occurs there too. H. magnifica var magnifica, in its classic form, is still further east at south of Riversdale itself. H. floribunda is known at Langkloof to the north-east, but otherwise there is very little available information regarding what lies between Vlakte and Heidelberg where H. mutica var. nigra, H. heidelbergenis, and the typical true form of H. floribunda occur.

My attention was first drawn to Melkboom by Kobus Venter who told me that there was a complex interaction there between several species (retusa, heidelbergensis and magnifica). He was with J.M. Esterhuizen who has also commented on what I recall was the relationship there of H. magnifica and H. heidelbergensis. I visited Melkboom with Kobus and indeed saw what I will refer to as heidelbergenis. At one point (squared brackets indicate position on the map Fig.24) it ([1] Figs.25a, b & c MBB7108) was growing near to but discrete from H. retusa ([2]Figs.26a, b & c MBB7107). These retusa-plants have smooth leaves with very rounded tips and in this respect hence incline towards H. mutica var. nigra. But on the extreme west wing of the Vlakte plateaux there is an apparent hybrid population of retusa ([3]Fig.27a, b JDV93-53, & c MBB7110) between two populations of heidelbergensis ([4]Fig.28a & b MBB71109, c, d, e, f & g JDV93-54, and [5]Fig 29a MBB7111 b & c JDV93-52). This small population is curious because it is situated between and yet so close, to populations of only one-putative parent. The other parent, presumably H. retusa, is absent. The fact of hybridity is not proven and is only speculative based on the spatial relationships and physical appearance of the plants as judged to be “intermediate”.

I had now seen H. magnifica at Kweekkraal East ([6]Fig.30a, b & c MBB6817) and West ([7]Fig.31a, b & c MBB6662), so was anxious to see what else occurred on the Vlakte. Those magnificas I had grown from seed, and I knew they consisted of a motley assemblage of forms between the more typical magnifica and atrofusca. What was the relationship then of these populations to the smaller heielbergensis plants at Melkboom? At this stage I never considered that H. floribunda would enter the picture.

Kobus came along with my wife and I to re-visit the area and explore between Melkboom and Kweekkraal West. The Vlakte Plateau has an irregular shape and has many buttresses separated by incised small valleys. The upper edges of these buttresses often comprise fairly skeletal soils with rock that probably accounts for irregular erosion of the plateau edge. The rock also seems to overly erodable clay and this is exposed by pressure bursts which result in a low clay bank and an extended apron of bare clay soil with here and there tufts of grass or low herbaceous plants. The valleys are more thickly and densely vegetated as the soil are deeper and retain water for longer. The rock and clay sites provide the habitat for the haworthias and nearly every buttress is populated. Thus we found a confounding array of plants which all seemed to indicate a continuum from the heidelbergensis-like plants on Melkboom to the magnifica-like plants at Kweekkkraal. The populations were disturbingly variable and yet differed also from one another. The description and quantification of such “difference” is probably an ultimate challenge to botany. The collections are [8]Fig.32a & b MBB7112, [9]Fig.33a, b & c MBB7113, [10]Fig.34a & b MBB7114, [11]Fig.35. MBB7115, [12]Fig.36. MBB7116, [13]Fig.37. MBB7117, [14]Fig.38a & b MBB7118.

My wife and I returned to the area East twice after that to further explore the plateaux. We first made these collections on Kweekkraal West [15]Fig.39a & b MBB7151, [16]Fig.40 MBB7152, [17]Fig.41a, b &c MBB7153, Fig.42a, b, c, & d MBB7154. The first two I regarded as heidelbergensis, the third inclined to magnifica, while the fourth was more positively magnifica including clones which would class as var atrofusca. On Kweekkraal East, significant finds were a population south of the Pretoriuskop inselberg consisting almost entirely of the var. atrofusca ([19]Fig.43a, b, c & d MBB7157) as opposed to several of the heidelbergensis/magnifica continuum we had seen on Kweekkkraal West. We also found H. floribunda on Pretoriuskop [21], southwest of (Fig.44 MBB7155) as well as on an unnamed inselberg to the west ([20]Fig.45 MBB7156). Exciting was that in the population of atrofusca, which was growing in a very white clay layer, was a plant of H. floribunda (MBB7158). It is extremely difficult in these field sites to recognise variants and distinguish what could have been hybrids, and we did not think there were such. However, about 50 meters away we came across a population of small heidebergensis ([22]Fig.46 MBB7159) like plants which we decided were hybrids – based on the fact that another 50 meters away was a population of floribunda. Again this is speculative.

At other sites we found several other populations that included both small ([23]Fig.47a & b MBB7160) and large magnifica ([24]Fig.48a & b MBB7161, [25] Fig.49 MBB7162) depending often on the nature of the pressure-bursts and the quality of the rock and clay. Often the clay was quite red and the rock very ferruginous (iron-stone). At other sites it was often very white and clean. The rock similarly varies from the very characteristic red-pebbly constituency of true ironstone, to the smooth white appearance of pure quartz.

On a still later occasion my wife and I visited Kweekkraal East again with Casper Mazurel of Holland. We had not explored the northern edge of the Vlakte plateau and needed to know more. Casper found H. retusa north of Kweekkraal East ([26]Fig.49 MBB7173) in the same kind of white clay that atrofusca occupied near Pretoriuskop – we also found floribunda again (Fig.49[23] – MBB7172). The curious thing about both the retusa populations from Vlakte, have very rounded leaf-ends (the mutica connection? – more later). The Melkboom population is relatively light-coloured and the more eastern population the deeper green/purple tones of magnifica. The small population at [25](Figs.47 MBB71620) seen on the previous visit (in white clay in which the plants were quite robust) then takes on a new face and could be imagined to be of possible “hybrid” (retusaXmagnifica) origin.

It required yet another visit to flesh out distributions and this was to the inselberg Rooikop. We were not quite sure what to expect and I did think that H. floribunda would appear again. Instead we found a series of small populations of plants I attribute to H. heidelbergensis/magnifica ([28]Fig.50 MBB7217)

As I have noted, variability in and between these populations is enormous. It is curious that H. floribunda only appears in the northeast of the study area and almost totally maintains its integrity where heidelbergensis/magnifica is excluded. The variant H. magnifica var. atrofusca is discrete in only one of these populations (Fig.42 – MBB7157) and this is the one exception where H. floribunda is also present. There seems to be a remarkably smooth continuum from H. magnifica-like to H. heidelbergensis-like plants.

I cannot say at all that Vlakte has been fully explored. There are many more possible habitats that we have not explored. While I am busy examining the evidence we have for a connection of mutica var. nigra to H. retusa, I find myself looking at the connection of H. heidelbergensis to H. magnifica with the implications of hybridisation (introgression is not a better word or concept, as both hybridisation and introgression imply an initial difference) involving H. floribunda and H. magnifica var. atrofusca which have rounded leaf-tips. Thus the saga continued.

Note: Kobus (J.D.) Venter made a presentation involving many of the above collections at the Aloe Congress at Calitzdorp in Sept.2003. This is due to be published in Alsterworthia. In his presentation he includes a geological map of the area and this shows that Vlakte is tertiary ferricrete overlying much older conglomerate rock. It is this ferricrete formation which provides a mosaic of small inselberg’s scattered throughout the southern Cape and playing a critical role in the occurrence of Haworthia).

Part 5: Continuing the saga.

On the way home after our last visit to Kweekkraal, Daphne and I stopped at Morning Star south of Heidelberg. We did this thanks to our friend Dr. Christie Kloppers who in discussing the distribution of H. marginata, let on that the owner of Morning Star was a relative of his. Morning Star is a locality recorded for H. marginata and as I had seen that species in the area many years before, I was anxious to confirm its survival there. As is the case in Haworthia there are so many considerations. Morning Star is not far from the Duiwenhoks river where the steep rocky riverbanks offer a continuum of habitats from north of Heidelberg all the way to the sea. A short way to the southeast is the locality Kransriviermond where H. mutica var. nigra has it origin. It is interesting to note that G.G. Smith made the connection of that population with three different accessions of H. mutica. Which goes to show how perceptions may differ – he had no compunctions about making that association as opposed to the opinions reported in the essay. The place Dassieklip is also on the lower reaches of the Duiwenhoks and this is where a very curious Haworthia is found which I have attributed to both H. floribunda and H. chloracantha. (Fig.54 MBB7164).

However, there is also something else. This is the collection MBB6663 (Figs.55a also MBB in KG107/74, & b JDV97-35, also Fig.27 in Pt.1) from immediately southwest of Heidelberg. This collection is cited in my revision under H. magnifica and that identification falls very far short of explaining its true identity or significance. I wrote an article in Aloe (34:4, 1997) discussing the problem of the “species” as they occur around Heidelberg. H. magnifica is barely mentioned and this particular collection suggested some introgression of H. floribunda. However, since that time I have come across several other populations to the west that must surely relate to this one at Heidelberg and impact on the relationship of H. magnifica to H. maraisii and H. mirabilis. Thus anything of this ilk to the south of Heidelberg becomes extremely important. That collection MBB6663 was instrumental in my early decision to treat H. maraisii and H. magnifica as one species

At Morning Star we were, by kind favour of Mr Coetzee Uys, able to get to the Duiwenhoks River. There we found H. turgida (Fig.56 MBB7219) on the rocks of the valley banks as we expected. It was surprisingly a rather small form (var. turgida) more reminiscent of its appearance on the sandstones north of Heidelberg, rather than the bigger var. longibracteata. But significantly we also found, in the immediately adjacent south-facing shale rocks, H. magnifica/floribunda (Fig. 57a & b MBB7218) as in MBB6663. The plants were smaller than that collection and there was more evidence of floribunda AND heidelbergensis in their appearance. We stopped and searched again about 3kms away on higher-lying ferricrete and in grass tufts, where we found plants of the same ilk (Fig.58a & b MBB7220). These two populations suggest fairly convincingly that H. magnifica and H. floribunda introgress (are continuous).

We were not finished. As a last effort we drove a short distance and stopped next to some exposed rock where we found H. mutica var. nigra (Fig 59a & b MBB7221). These are very dark-green almost black, shiny-leaved plants with the rounded leaf-tips we associate with H. mutica. One of the clones was almost identical to a plant of H. retusa (so-named) from north of Kweekkraal (MBB7173) where one could speculate that the rounded leaf-tips and darker colouration had some connection to introgression (that word again) with H. magnifica var. atrofusca. The second plant illustrated (Fig.59b) is somewhat of an aberration that I selected to emphasise that identifications are often very tenuous.

In my discussion of H. incurvula in Aloe ( 36:34, 1999), I suggest we need a new language to discuss, explain and name haworthias. We need a better conceptualisation of names and what they mean. In taxonomic botany, the name of a species is linked to a “type’ which is desirably a herbarium specimen, but it could be an illustration of some kind. It is often simply assumed, perhaps even unconsciously, that this “type” is typical. We all (nearly all) assume that anything so named will be identical or near identical to that type. Conversely we assume that anything different from the type should have another name and ipso facto be another species. The concepts of subspecies and varieties are an extension of this way of thinking. The nomenclatural code which seeks uniformity and stability in the way we name plants cannot legislate or prescribe when and where names should be applied and nor at what rank. Where it does seem to fall short is the requirement for the automatic creation of a typical rank when an equivalent rank is created. Here it seems to be making the same assumption that all plants of a species are the same. Thus when a new, say, variety is described, there is a typical variety that stands in juxtaposition to the new. This is patently fallacious. What is required is a re-description of the species to include the variation of the new lesser rank, and only those individuals which meet the varietal description become identified by an added name. The residue forms the core of the species and are designated by only that name?

What we need in addition, is the adoption of a definition of a species as a system of living organisms which is named by a convention recognised as a language requirement, and not as any scientific process or achievement. The name is only the passkey to information – the key by which we generalise about a particular living system. (I have since written a chapter which suggest that species are fractal, and that we will need to adapt our thinking to this kind of geometric/mathematical pattern).

Part 6: Another twist to the story.

Until recently I had seen very little of the haworthias immediately west of Heidelberg. Kobus Venter has several collections, some by J Esterhuizen, and these included plants from Uitkyk immediately southwest of the town (Fig. 60a & b JDV89/2) as well as from further west. He also has two collections from immediately north of the town where previously I have referred to only one. Taking these first, I think it is quite clear than they both suggest the continuity of turgida with heidelbergensis, while one of the collections suggests a closer similarity to the plants from Klipdrift of Part 1. The Esterhuizen collection from northwest of Heidelberg (Fig.61 JDVsn) seems to support such a contention.

But I really want to deal with plants west of Heidelberg. The locality is referred to as Die Plotte but actually the area is partly township land, an area of smallholdings and sections of what was a very large farm Hooikraal. Dekenah and thus G.G. Smith original site of heidelbergensis may be non-existent now because of the creation of a rubbish-dump site immediately west of the town. Plants similar to the original heidelbergensis can still be found southwest and further west (and of course immediately east of Heidelberg which I had concluded (wrongly and influenced by Dekenah) was the type locality. Kobus’ collection from Die Plotte (Figs. 62a, b & c JDV91/142) are of smaller plants while JDV91/146 (Figs.63a & b) from the same general area, are bigger plants. These are intermediate with the Esterhuizen plants northwest of, and typical heidelbergensis from east of Heidelberg (Figs. 64a, b JDV87/1 & c MBBsn).

When Kobus delivered his paper at the Aloe Congress 2003 at Calitzdorp he met up with Mr. J. Hoffman. I had met him at Worcester many years before and he had told me of plants west of Heidelberg. Thus I undertook to renew this contact and went to see him at Heidelberg. He took me to the northeastern corner of the farm Hooikraal which borders on Die Plotte and which is also west of the town dumpsite. Apart from showing me H. marginata, he also showed me a population of small heidelbergensis (Figs. 65a, b, c & d MBB7233) and then a population of very large plants that were quite remarkable (Figs. 66a, b, c & d MBB7234). The plants included one that even resembled a large sturdy mirabilis – and Esterhuizen commented in an article he once wrote about the spotting on the back of the leaves of “heidelbergensis” which he likened to mirabilis. Generally the plants are with darker green and purplish hues that I associate with heidelbergensis or even magnifica. There were very yellow-green forms similar to what I saw many years ago at Skeiding further west of Heidelberg. These are plants that Esterhuizen (and myself too) has referred to as retusa, and I would agree except that they fall in the query zone between retusa and turgida var longibracteata i.e. there is continuity between the two species. In fact Kobus and I revisited Skeiding and I thought the plants (Figs.67a & b MBB7240) were almost identical to H. retusa at Melkboom (Fig.26 MBB7107 in Part 4), although the latter tended to have rounded leaf-tips. H. magnifica, MBB7239, was also present in a rare situation for these two species to be so closely located within meters of each other). We also visited a population immediately north of Heidelberg (Figs. 68a & b MBB7236) that is not far distant from the two Nature Reserve population already referred to. Had I seen this population in 1975, I may have been more adamant in maintaining that H. retusa and H. turgida were but one species. The plants were generally big and very proliferous and one could not help reflecting on how similar they were the population that gave rise to Scott’s H. geraldii (H. retusa var.). The collection from northwest of the Heidelberg Nature Reserve (Figs. 69a, b & c JDV89/5) must surely suggest that there is a continuity of H. turgida with the Klipdrift plants illustrated in part 1.

My conclusion is that there is now a proven continuity between turgida, heidelbergensis, magnifica, retusa, mutica var. nigra, maraisii, pygmaea and even floribunda, chloracantha, rossouwii and variegata. The continuity is also with emelyae and its varieties north of the Langeberg mountains. At the same time some of these elements may occur together and so appear to be discrete. Thus a taxonomic solution for one set of collections may not be appropriate for another.

Paul Forster and Russel Scott (both from Australia) spent some time in South Africa while attending the Calitzdorp Congress, and I was privileged to have them join me in the field at Heidelberg. We explored the middle Duiwenhoks river between Dassieklip and the town of Heidelberg. I had expected that such exploration would throw some light on the strange Dassieklip population (Fig.56 MBB7164). In my Revision (1999), I have ascribed it to H. floribunda simply for the want of a better solution outside of regarding it as a discrete species based on a single population!).

Apart from seeing H. turgida we also found find populations of plants at Witheuwel (Figs. 70a, b & c MBB7227) and Somona (Figs71a, b & c). These are more like the Melkboom and Kweekkraal heidelbergensis/magnifica collections. I would have expected a similarity to MBB6663 (SW Heidelberg), referred to in part 5, figs 2 & 3) or to MBB7218 and MBB7220 which I would ascribe to floribunda/maraisii rather than to H. magnifica – tenuous as such a distinction is. Essie Esterhuizen has apparently discovered a similar population to KG107/74 along the Duiwenhoks close to of Heidelberg. It must be noted that Matjiestoon, the locality for H. heidelbergensis var toonensis (Figs.72a, b, c & d MBB7165) is only about 15km west of Dassieklip. Thus while I am writing in the context of H. mutica var. nigra, I have drifted helplessly into discussing H. heidelbergensis. This is the crux of the whole thing about Haworthia – especially the subgenus Haworthia – an intricate network of relationships that just will not resolve.

Part 7: Completing the saga.

So far in this series of articles I have dealt with H. mutica var. nigra as a system of populations typified from the southernmost population at Kransriviermond, and extending through eight known populations to Klipdrift northwest of Heidelberg. Then I considered the role of H. turgida in part 3. In part 4 I dealt with the very complex situation that seems to occur between Riversdale and Heidelberg, followed in part 5 by discussion of populations along the lower Duiwenhoks River. In part 6 the discussion and illustrations are of plants from mostly west of Heidelberg.I have discussed to some degree the possible relationship of these populations to each other to H. turgida, H. retusa, H. heidelbergensis and H. magnifica. Each of those systems in turn interacts with others and it becomes highly doubtful that we are in fact dealing with discrete systems at all.

If we now switch the attention to H. mutica and point to some of the populations that constitute my concept of that species, it may help to crystallize aspects of my classification. I will not deal with all the material at my disposal as is too extensive for the purpose. The name H. mutica is based on an illustration in the Royal Herbarium, Kew, of a plant of unknown origin (Fig.73). I use the name for a series of populations all west of the Breede River, from near Drew in the north, to near Bredasdorp in the south. These populations all seem to be discrete from other species in that general area, which are H. mirabilis, H. maraisii, H. rossouwii, H. heidelbergensis, H. reticulata and H. turgida. Those species display their own interactions as follows:

H. mirabilis never occurs in any close association with any other species (of the same subgenus) including H. maraisii or with H. heidelbergensis. Where it may, is where H. mirabilis var. badia occurs in close proximity to H. maraisii at Napier. I can be suggested that here the two elements are introgressive and that var. badia is actually the consequence of this introgression (again the word implies interaction between different things). H. maraisii never grows in association with H. heidelbergensis except for the place Rooivlei north of Bredasdorp where this H. heidelbergensis var. minor could in fact be a variant of H. rossouwii. It should be noted that H. turgida var longibracteata also occurs here as a very isolated population.

If one extends these observations it will be found that very few species maintain their identity in close proximity to any other. H. magnifica may occur in close proximity to H. tugida or H. retusa, but the latter two never to each other. H. magnifica is not discrete in any sense from H. maraisii and two species are recognised simply as a device to assist discussion where we have a western (maraisii) and an eastern (magnifica) counterpart. Neither of these ever occurs near to, or with, H. heidelbergenis. We actually need to again consider this last-named species very closely. It is typified from a population just west of Heidelberg (as Esterhuizen rightly pointed out, and it is by fortunate coincidence that my assumption drawn from Dekenah that it was east, does not alter the basic perception of what the species looks like). H. heidelbergensis has by default, and from simple circumstance and complex reality, become a hodge-podge of populations which interdigitate between H. mirabilis, H. maraisii and H. magnifica. H. floribunda is a curious anomaly that is widely distributed and is known to hybridise with H. turgida, H. magnifica var. atrofusca and with H. pygmaea var. argenteo-maculosa. There is some evidence that it introgresses with (or has never segregated from) H. magnifica (synonymous maraisii) south of Heidelberg, and similarly with H. heidelbergensis (synonymous also with maraisii) south of Swellendam.

H. mutica only grows in the close proximity of H. mirabilis at Rondeheuwel south of Stormsvlei. At Sanddrift, Drew it is in close proximity to H. heidelbergensis in a form which is akin to H. maraisii. Further to the southeast it is in close proximity to H. maraisii. At Napky these two elements are also close.

My argument for maintaining H. mutica as discrete from H. retusa was based on the observation that it was never necessary to invoke H. turgida in the equation as it is when discussing H. retusa. It also is never introgressive with H. maraisii as H. retusa seems to be with H. magnifica east of Riversdale, nor with H. heidelbergensis as H. retusa seems to be at Kweekkraal. Nevertheless this decision is not indisputable. I have always borne in mind that H. mutica has some affinity with H. pygmaea. H. mutica seems to have a retusa-like origin whereas H. pygmaea has a magnifica-like origin. In neither case can one be sure that H. turgida is not prominent in the ancestry.

A not-so-curious thing about H. mutica is its variability too. Just like any of the other “species”, it has many faces. The one I would like to mention is the similarity of plants of H. mirabilis var. badia from the western-most known point of its distribution. This is not readily apparent. But is we look at plants at the western end of the population viz. Sandfontein Napier (Figs.74a & b MBB6987), the plants begin to depart from the more classical form with the strongly recurved leaves, and begin to resemble more typical var. mirabilis as at Mierkraal Bredasdorp (Figs.75a & B MBB7090). What has astonished (even) me is that some of the clones form a very close match with H. mutica, especially with south (Figs.76a & b JDV96-16) and north of Napky (MBB7031 respectively). Thus we are now thrown into (an admittedly obscure) relationship of H. mutica and H. mirabilis (there is also a similarity with a clone of H. magnifica from the problematic “south of Tradouw site” (Fig.77 MBB6666). To my knowledge H. mutica and H. mirabilis only occur in close association at one place. This is at Rondeheuwel south of Stormsvlei where the mirabilis is atypical and evidence of the continuity it displays in so many places with H. maraisii. My collection (Fig.78 MBB6982) from Hasiesdrift north of Bredasdorp seems to be a good representation for a concept of H. mutica. The habitat photo (Fig.79), however, raises such strong images of H. retusa that doubt about the affinity of the var. nigra cannot easily be laid to rest.

There the saga for the moment must rest. The proper taxonomic place of H. mutica var. nigra sensu Bayer is simply not very significant given the huge problem which is only touched on here. This is the interplay of H. heidelbergensis with H. maraisii, H. magnifica, H. mirabilis, H. turgida, H. retusa, and others. I should say of all the populations (should I count them?), I know which can be attributed to these “species”. ♦

Pingback: New finds in Haworthia. - Haworthia Updates

Pingback: Mystery - part 27, West of Riversdale - Haworthia Updates

Pingback: Retusa Travels - Haworthia Updates